Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Exposure to pathogens is a useful way of tuning up the immune system, according to medical lore. As businesses across the world assess the impact of Monday’s hours-long Amazon cloud outage, a similar principle may apply.

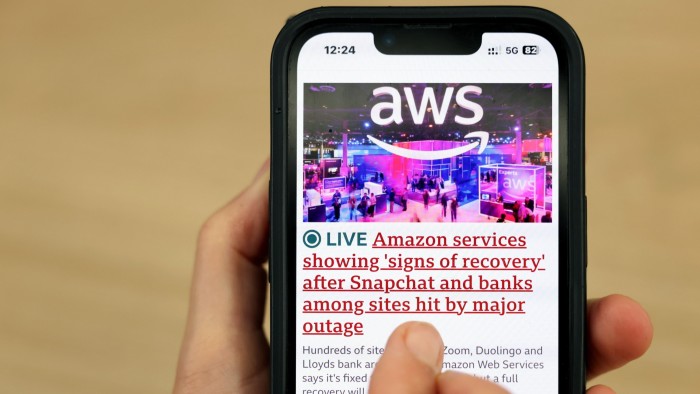

Users of services, from Zoom and Snapchat to Reddit and ChatGPT, found themselves dangling after Amazon experienced a glitch in its US east-coast cloud operations. In a particularly unhelpful twist, Slack, the messaging service many companies’ IT folks use to share intel on outages and threats, was itself temporarily out of action.

This isn’t the first outage of its kind, but as more data — and eyeballs — migrate online, the stakes rise. When Amazon’s cloud offering stumbled briefly in 2017, due to an engineer’s typo, it was a business with $20bn of annual revenue; today Amazon Web Services makes almost $130bn, according to analyst estimates gathered by LSEG, and is growing by about 20 per cent a year.

On the face of it, such hiccups bolster the case for contingency planning. No sensible business puts all of its eggs in one basket. Still, diversification isn’t simple. Cloud customers have multiple ways of spreading risk: duplicating data across different servers, sites and geographies. But each brings costs. For some Amazon customers, even hosting data outside the US didn’t help: certain critical functions such as “identity management” updates still depend on the eastern US, creating a single point of failure.

A more sturdy option is so-called multi-cloud computing, where data is shared between more than one cloud provider, from big players such as Google and Microsoft to smaller upstarts like DigitalOcean and Vultr. Costs climb further, of course; many charge not just for storage but also levy a toll or “egress” fee when data moves through the pipes.

Mini-disasters tend to focus minds, though, and change priorities. Customers often start from the premise that uptime of 99.9 per cent will suffice. But that still leaves the potential for eight hours and 46 minutes of blackout a year. In practice, even “three nines” of reliability may feel too few. Companies are already spending escalating amounts on cyber security; resilience may deserve more attention, too.

Of course, if the response to potential outages is that companies attempt to build in more slack, then there will be obvious beneficiaries: cloud and data centre providers themselves — including, to some extent, Amazon. That’s not unhelpful, given builders of computing infrastructure are investing hand over fist. If a bubble is forming, an anxiety-induced increase in corporate tech budgets might keep it inflated a little longer.