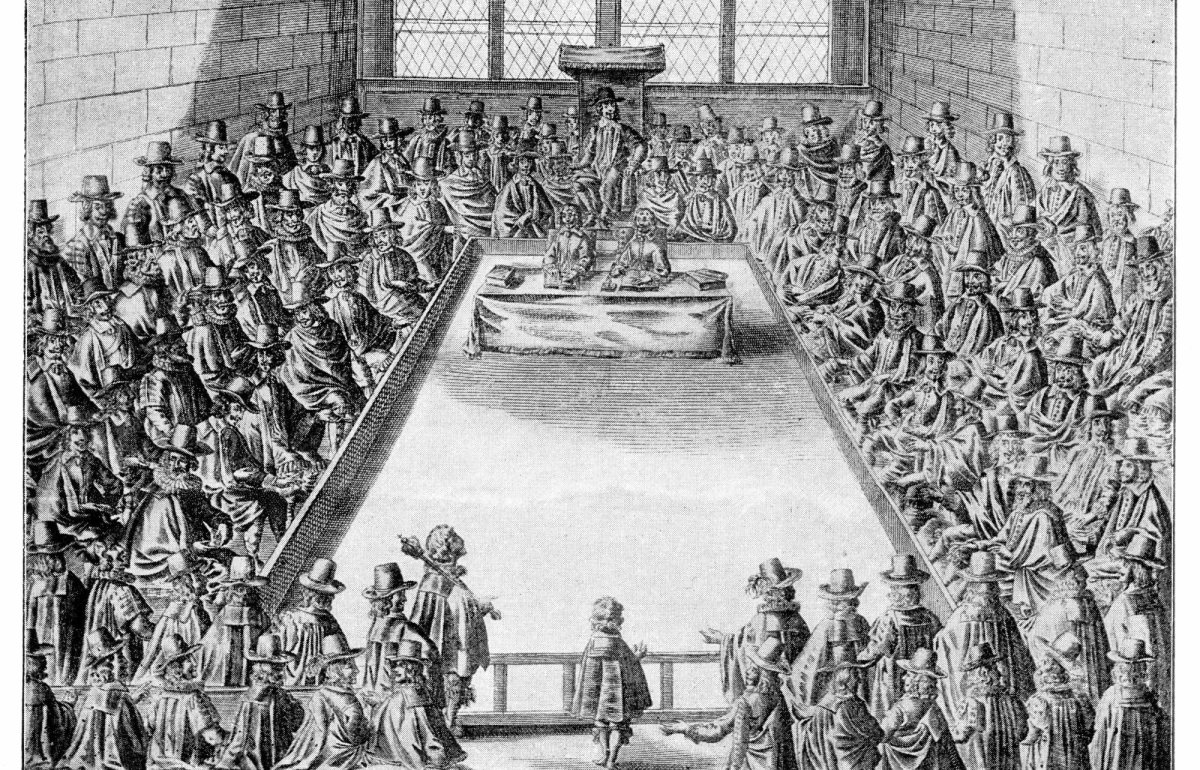

House of Commons during the reign of King Charles I | Image by: Timewatch Images / Alamy

4 min read18 min

John Rees has written a page-turning and powerful reminder of how Parliament and the people once wrested control from an arrogant executive

At a time when the government has proscribed a protest group as a terrorist organisation, is arresting hundreds of peaceful protesters and is considering giving the police new powers to restrict and possibly ban demonstrations, this wonderful book is an essential reminder of the vitally important role popular protest has played in securing our parliamentary democracy.

It’s not often a work of such detailed scholarly research reads like a page turning novel, but John Rees has accomplished this in his history of the build-up to the English revolution in the 17th century.

Henry Marten | Image by: Classic Image / Alamy

The book is more than a historical account of how Parliament and the people of this country wrested control from a belligerent and arrogant monarchy and founded a democracy. Fascinating though that story is, what is more important, especially for parliamentarians, is the description of how a group of radical MPs, the “fiery spirits”, could take on the might of a monarchical dictatorship, mobilise the masses of the common people and in doing so transform our society and political system forever.

There are few handbooks for prospective parliamentary candidates or new, fresh faced, incoming Members of Parliament. The ones that exist are tedious, uninspiring descriptions of parliamentary procedure combined with a few tips on how to climb up the greasy pole, usually by ingratiating yourself with the party leadership or at least make a name for yourself.

This book should be issued to every new MP. It is inspirational. It demonstrates how a small group of like-minded Members used every parliamentary device they could draw upon or invent to challenge centralised power and win.

Henry Marten, possibly the most prominent fiery spirit, expressed (for the time) the most audacious and shocking view that in his opinion, “I do not think one man wise enough to govern us all.” It was on that assessment that a revolution eventually took flight.

What I find remarkable is that in Parliament there is no celebration of the role of the fiery spirits – no statue, no memorial

The core of fiery spirits in the Commons – including Marten, William Strode, Alexander Rigby and Peter Wentworth – courageously posed the questions put by the English people at large. Why should one man, the king, be allowed to wage wars, levy taxes, and imprison, torture and execute dissenters from the state religion without any say by the people themselves who endured these impositions?

What is fascinating in this period is how the radicals reshaped political decision making and incrementally laid down the procedures that removed the monarchy from the role of the executive.

Historically the basic constitutional rule of thumb was that the king and his privy council served as the executive whilst Parliament was summoned at the discretion of the king to levy the taxes and pass the laws the executive desired. Rees describes how, in a creative whirlwind at times, the radicals in Parliament set up committee after committee to consider and address the issues facing the country, gradually transforming them into playing an increasingly executive role and wresting control from the monarch and his appointees.

Removing the power of the king to dissolve Parliament was key to securing its independence. The resistance of an obdurate and threatening king could not have been broken by parliamentary debate alone. Too often the challenges in Parliament to the king’s powers resulted in imprisonment for the radicals.

It was only the alliance of radical parliamentary leadership with a mobilisation of the people, often through the Puritan pulpits, that was able to secure the long-term security and freedom of the emerging democracy, even when monarchical power was replaced by a military republicanism under Oliver Cromwell.

It was only the alliance of radical parliamentary leadership with a mobilisation of the people, often through the Puritan pulpits, that was able to secure the long-term security and freedom of the emerging democracy, even when monarchical power was replaced by a military republicanism under Oliver Cromwell.

What I find remarkable is that in Parliament there is no celebration of the role of the fiery spirits – no statue, no memorial. It’s as though they have been written out of history. Maybe it’s because leaders and governments do not want to be reminded of the power of an alliance between radicals in Parliament and the people protesting at our door.

John McDonnell is Labour MP for Hayes and Harlington

The Fiery Spirits: Popular Protest, Parliament and the English Revolution

By: John Rees

Publisher: Verso Books