When the Nobel Committee announced that László Krasznahorkai had won this year’s prize for literature, I pulled one of his novels off the shelf. I wasn’t familiar with his work, but the words “difficult and demanding” drew me in.

I’ve always been drawn to long, complex books such as “War and Peace,” “Roots” and “Cryptonomicon.” They stretch across generations. But this time, with Krasznahorkai, I couldn’t make it past the first three pages. My focus slipped. Somewhere along the way, I had lost the endurance that deep reading requires.

It’s easy to blame phones, social media and the endless stream of short-form content. Screens compete for our attention, training our minds to crave instant gratification rather than depth. But screens are only part of a larger pattern: a growing discomfort with stillness and the slow work of concentration. Distraction has become the cultural default.

Reading isn’t just an academic skill or pastime. It’s how we build complexity within ourselves in a time that rewards simplicity and quick conclusions. Deep reading means lingering with a text and allowing it to challenge us. It slows us enough to notice nuance, sit with ambiguity and connect ideas that seem unrelated. It strengthens the mental muscles we need to navigate an increasingly complicated world.

Brian Mathews

In “Proust and the Squid,” neuroscientist Maryanne Wolf explains that the human brain wasn’t born to read; we taught it to do so. Reading strengthens the neural pathways that make imagination and empathy possible. It doesn’t simply transmit information; it builds the architecture of critical thought.

For most of human history, reading was a privilege of the few. As literacy spread, it reshaped our world. People could interpret sacred texts, study new ideas and imagine different futures. The printing press accelerated that freedom, moving books from monasteries into homes and coffeehouses. Reading democratized thought. That same power to think independently is what’s at stake again today.

That ability now feels fragile. Reading for pleasure has declined sharply in recent decades. Many people struggle to finish full-length books. We skim, scroll and summarize. Increasingly, we think in shorter bursts, leaning on artificial intelligence to condense what once demanded full attention. AI can be a useful tool for inquiry, but it works best as a partner to reflection, not a replacement. The challenge is using technology to extend our reach without letting it erode our capacity for depth.

What if, despite all our technology, we are returning to a culture built more on regurgitation than reflection? Our digital world is full of narration through posts, clips, comments and reactions, yet so little of it invites us to pause and think. Some observers argue that we are entering a post-literate era that favors immediacy and performance over reasoning and depth. We may know more than ever, yet think less deeply about what any of it means.

To read a book today is, in its own quiet way, an act of rebellion. It resists speed. It refuses optimization. It asks for full attention in a world that profits from distraction. When I pick up Krasznahorkai at lunch, it feels like a small protest. His long, winding sentences offer no shortcuts. Reading him reminds me that some forms of thinking cannot be rushed and that not every kind of meaning can be summarized.

Reading is also a form of self-governance. It’s how we choose what enters our mind and how ideas connect in ways no algorithm can predict. The physicist who reads poetry, the engineer who studies philosophy, the novelist fascinated by biology are all exercising the same muscle of synthesis. Every voice expands our map of understanding, and reading across difference stretches that map even further.

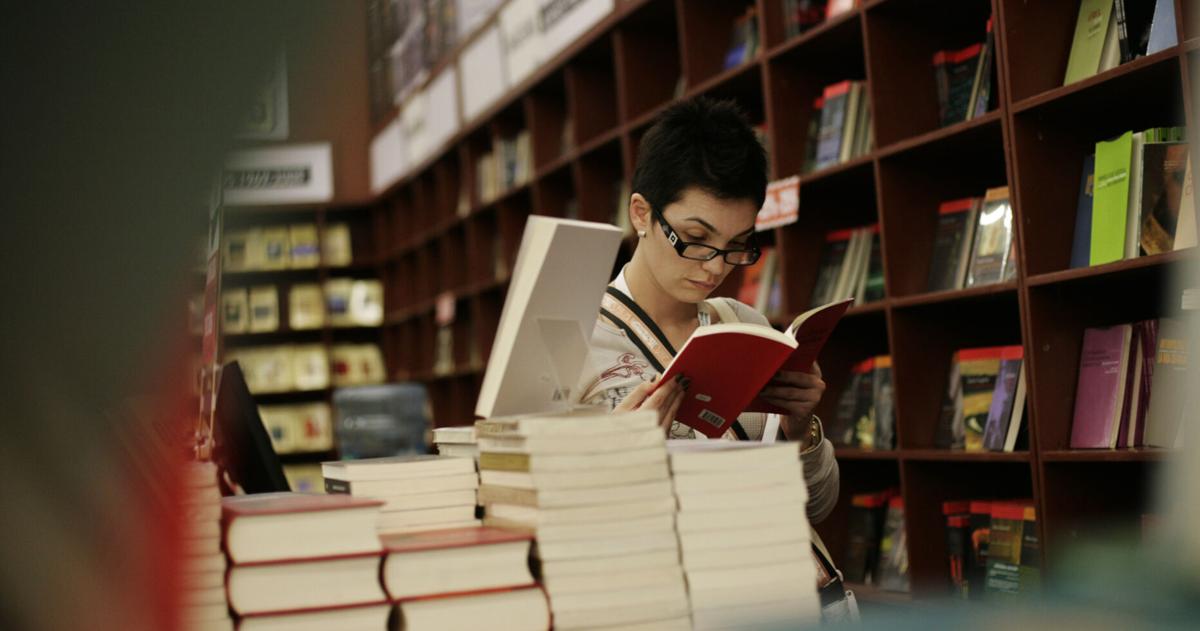

Libraries stand as sanctuaries for this work. They are among the few places left where thinking still feels unhurried and curiosity is allowed to take its time. Within their walls, ideas coexist across time and discipline, offering a living dialogue that shows how intellectual strength grows from diversity.

I’m sticking it out with Krasznahorkai, reading a few pages each day. My goal isn’t deep analysis but rebuilding focus, to rediscover the kind of attention that feels expansive, when the mind is free to wander and wonder. These small choices remind me that reading is both self-care and social care. It strengthens our inner lives so we can more fully engage the outer world.

Maybe that’s the invitation: Set the phone aside, and pick up a book that challenges or surprises you. Give your attention something demanding to work on. Reading, after all, is how we remember who we are and what it means to think deeply in a world that rarely slows down.

Brian Mathews is the dean and university librarian of Elon University’s Carol Grotnes Belk Library.