Yûta Shimotsu’s sophomore feature is an enlightening social satire about the dangers of conformity and assimilation, brought to life through a chilling body horror experiment.

“Japan is the best! Japan is the best!”

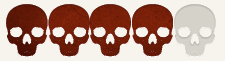

There is no shortage of uncomfortable imagery and surreal nightmare fuel in American horror movies. However, the chilling visuals that are born out of J-horror classics like Ringu, Ju-On, or the extended works of Takashi Miike are on a whole other level. There’s a nightmarish dream logic to so many Japanese horror films that can make them feel like they’re truly haunted. Yûta Shimotsu (Best Wishes To All) creates an incredible, unpredictable body horror masterpiece that doubles as an indicting satire of Japan’s society. Shimotsu’s New Group feels so much like a lost Sion Sono movie, in particular the director’s infamous Suicide Club, while doubling as the best adaptation to a Junji Ito story that doesn’t exist. Ito, Sono, Miike, and even something like Human Centipede coalesce together to form the twisted human pyramid that is New Group. It’s a modern J-horror masterpiece.

It doesn’t take long for New Group to unleash its cosmic terror on Japan. The film kicks off with a collection of aggressive visuals that bombard Ai’s subconscious and foreshadow the looming division. Ai (Anna Yamada) and Yu Kobayashi (Yuzu Aoki) are humble, reluctant characters who are used to ease the audience into New Group’s grander ideas. Ai and Yu, as their names explicitly suggest, are meant to be echoes and inversions of each other. Ai is introverted, shy, and obedient, while transfer student Yu can’t help but question every rigid custom and belief that he’s presented with. Yu prides himself on his independence and the importance of building an individual identity. Ai, alternatively, is desperate to fit in and feel like she’s a part of something bigger. There’s a strong enough foundation to both of these characters that makes how they negotiate the film’s central problem very entertaining.

Ai and Yu try to make sense of the spectacle before them, which allows New Group to engage in some deeper and more profound questions. The film is rich with examples where individuality breeds division and is treated like a problem. Bullying is the most overt example of this, but New Group subtly indoctrinates the audience with recurring punishments for those who fall out of line and don’t reinforce hegemony, whether it’s someone who can’t march in sync with the rest of their peers or art classes that explicitly squash individual expression in favor of replicating an existing style. All this is in favor of creating a powerful feeling of belonging and acceptance for those who fit into society’s neatly-regimented puzzle, and isolation and rejection for those who seek to defy. New Group features so many casual acts of conformity so that it’s clear that reputations and social standing are paramount to these characters.

Shimotsu’s Best Wishes To All previously unpacked Japan’s rural depopulation issues and people’s prescribed roles in society. New Group instead examines societal conformity and the toxic groupthink that erodes independence. This subject matter is ripe for discussion in Japan and something that many films put under the microscope. However, New Group is the only one that breaks down the idea through a hypnotic human pyramid that’s made out of hundreds of people.

New Group is such a fascinating experimental masterpiece because of how naturally it segues from these everyday acts to the perilous sight of a human pyramid that slowly, gradually begins to accumulate people. What initially seems like a playful lark turns into a hive-mind-like act of preservation. It’s an absurd act, but it’s easy to reduce this rebellious performance art into a community act of unity. And if being a part of this human pyramid is an act of togetherness and support, then those who don’t take part in it must clearly want the opposite. More and more bodies get added to this human pyramid to the point that it stops looking like a collective mass of humans. It’s apt that joining this pyramid, while presented as empowering, is an erasure of identity as individuals give up and retreat to the comfort of this blissful obedience. The feeling that these students experience in New Group is hardly unique to Japan, yet it’s an effective setting where not fitting into society’s prescribed borders is akin to not existing.

New Group revolves around a genuinely surreal premise, but it’s rather masterful in how it normalizes such abrasive imagery. The growing human pyramid creeps up and fills the frame until it just feels like another static object and not some writhing mass of individuals because, at a point, it’s not anymore. It’s become this singular abstraction that’s truly the sum of its pieces. Director Shimotsu wants the audience to be numb to this spectacle, just like the compliant individuals who pledge themselves to the “Greater Good.” The film’s final act brilliantly doubles down on this premise so that rebellion and individuality can just become another version of conformity. An esoteric picture like New Group that vibes on visuals and ideas, rather than specifics, is bound to face issues when it needs to start wrapping things up and making sense of everything. New Group doesn’t fall apart with its ending. It finds a conclusion that’s the perfect way to bring all this to a head that also manages to be just as absurd as the central premise.

It’s all an extremely effective way to highlight how perceived happiness and compliance don’t always translate to fulfillment and what’s actually best for someone. The bodies that the human pyramid amasses submit themselves to a greater whole and lose themselves in the process, but they couldn’t look happier during their assimilation. It’s a reminder that the veneer of perfection and bliss can surround an empty shell. Alternatively, New Group argues if this mass ignorance and subservience is really that bad. It’s a chilling perspective to consider during a time when it’s easier for many to put their heads down and join the growing human pyramid, rather than fight against it.

New Group’s story elegantly unfurls, revealing a method to this madness, as each new layer helps make sense of the scenario. New Group makes the audience question its insane visuals that are designed to unnerve. This psychological assault also finds the perfect moments to weaponize some bizarre black humor. One of the silliest and most successful moments from New Group involves a romantic embrace between two characters that looks like it’s being acted out by aliens. “Is it a horror or a comedy?” gets innocently asked early on in the film. One can’t help but feel as if it’s a question that’s applicable to the entirety of New Group and the audience’s forced state of mind over how to react to all this. New Group wants the audience to simultaneously cackle and cower. This becomes easier as the film grows progressively absurd and crescendoes to such a peak where it feels like an anime that’s come to life. It’s one of the most insane finales that I’ve ever seen.

Yûta Shimotsu’s New Group is one of the most exciting horror movies to come out of 2025 and hopefully just the start of what will be a busy career for Shimotsu. New Group solidifies Shimotsu’s status as an anarchic and experimental storyteller who cuts to the core of universal topics through extremely unconventional means. At only 82 minutes, New Group doesn’t waste the audience’s time or belabor this surreal experience. It’s a bold step forward for J-horror that’s needed now more than ever, now that disruptors like Sion Sono are out of the picture. New Group is outrageous in all the right ways and successfully turns an acrobatic formation into existential terror.

New Group screened at the Brooklyn Horror Film Festival; release info TBD.

![‘New Group’ Feels Like A Lost J-Horror Classic That Turns The Human Body Into Abrasive Architecture [BHFF Review]](https://www.newsbeep.com/uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/New-Group-Human-Pyramid-Moves-Through-Hallway.jpg)