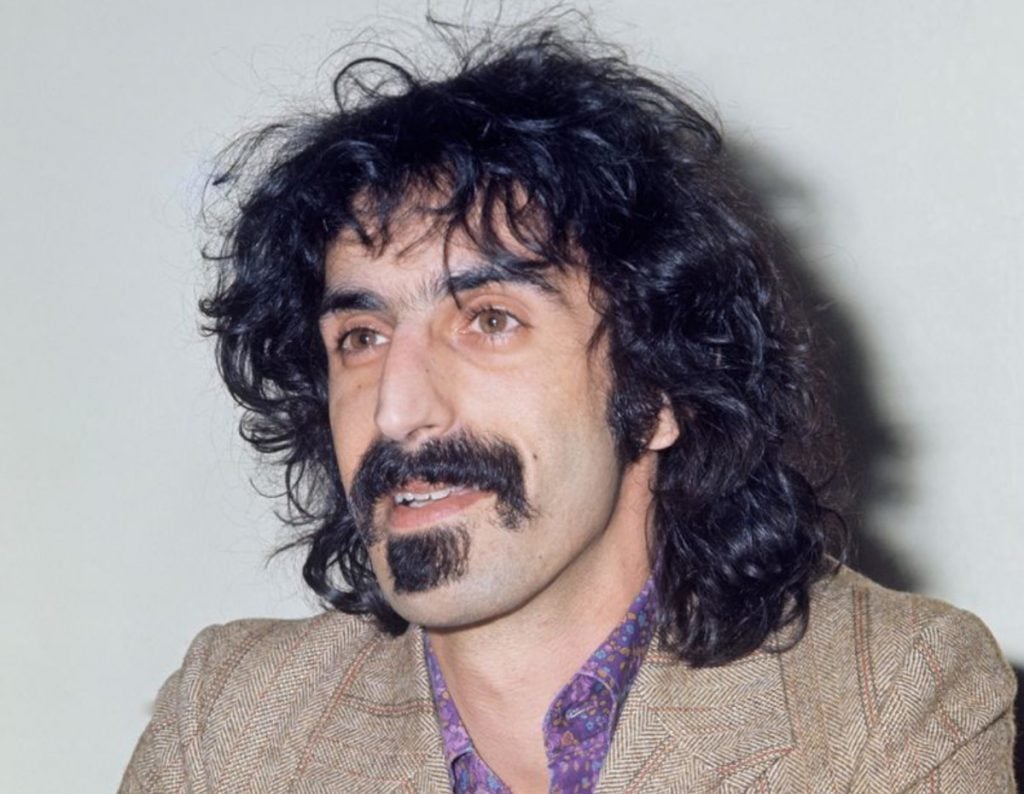

(Credits: Bent Rej)

Mon 27 October 2025 19:18, UK

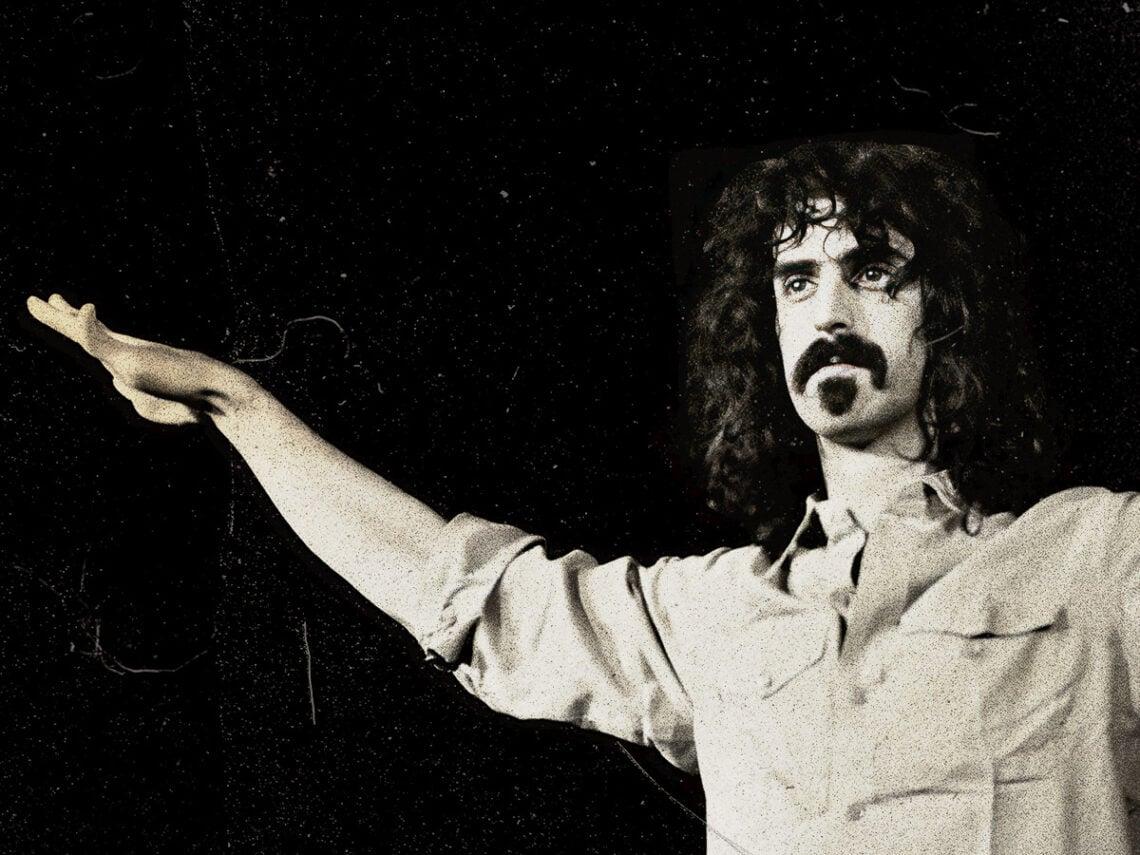

With a level of fury, John Lennon once labelled Frank Zappa a “fucking intellectual”. It’s a brilliant insult. And despite the bespectacled Beatle landing it disparagingly, Zappa would’ve no doubt appreciated it. He was, after all, a self-proclaimed nerd of the music world.

He happily spent years peddling exactly the same theory. Zappa wasn’t just a rocker; he wasn’t simply a gifted guitarist or even a grand composer. Zappa was an artiste, with the extra inflexion on the extra “e”. He was a jazz enthusiast, a cultivator of culture and a determined individual with just a small penchant for rock ‘n’ roll. But you’d be a fool if you thought that rendered his songs stuffy and over-considered.

Take the madness of 200 Motels, for instance: an effort, ironically, right up Lennon’s street, thanks to the whirlwind of mania akin to the Liverpudlian’s beloved director Alejandro Jodorowsky. This frenzy unfurls like Night at the Museum filmed at an odditorium instead, and all the oddballs and artefacts of history therein are sleep-deprived to the point of delirium, imbuing the resultant party with an aura of intense surrealism.

However, it might not be a surprise to ardent Zappa fans that this wasn’t necessarily inspired by the psychedelia of the day, and least of all LSD, with the moustachioed rocker remaining staunchly sober throughout his career, but rather the quirky composers of the past that Zappa had come across in his “intellectual” research.

The Californian recognised that forward-thinking experimentation in music was born in the 1960s. Plenty of musicians had been innovating with the form and still trying to make it appealing long before that. One of which was the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók.

When Zappa appeared on Castaway’s Choice, the American radio rip-off of the long-running BBC incarnation Desert Island Discs, in 1989, he was asked to pick his favourite song. He went with Bartók’s ‘The first movement from Third Piano Concerto’. Zappa offered up a simple explanation as to why it was his favourite: “I think it is one of the most beautiful melodies ever written.”

The Hungarian pianist behind the melody lived from 1881 to 1945. During that time, he was renowned for blending traditional folk with his own elevated musicology, determined to keep his country’s cultural history alive in a period of great upheaval that threatened to see traditions conquered by foreign cultural hegemony.

However, Bartók, like Zappa after him, also figured, ‘what good are traditions for the mere sake of keeping something old alive’, the past has to be preserved with a progressive intent. Thus, Bartók didn’t just rehash folk tunes; he studied them endlessly, travelling with Magyar folk troupes across the land learning their musical ways, then he picked them apart, and restructured the musicology with a contemporary mindset. He somehow made the asymmetrical rhythms of the wayfaring dance music almost pop-like, and Zappa adored it.

As Zappa explained regarding his singular inspiration: “Bartók used to collect folk songs and use them in his compositions. In my case I collect folk lore of a verbal kind, from the street or from the people immediately surrounding the world of the group, and convert them into a musical reference.” In doing so, Zappa placed the counterculture age in a satirical tapestry of strange, unfurling scenes.

But as he did so, he never forgot the touching musicology of Bartók’s ‘First Movement’ that endeared him to the composer in the first place. As he sheepishly recalled to Castaway’s Choice’s host Nigey Lennon when the song was spinning and he was sure he was off the air: “The first time I heard the main melody in the first movement of this thing, I almost (now don’t laugh) cried.”

Related Topics