Earth’s moon is a treasure trove of resources. Space agencies around the world are planning missions to access and use lunar volatiles, which include hydrogen, water, helium, carbon dioxide, and carbon monoxide, in order to produce fuel sources, breathable air, and even drinking water — all with the goal of establishing long-term presences on the moon.

But much is unknown about the availability of water ice on the moon, or even what data is missing that could help fine-tune lunar exploration by both robotic probes and human explorers. That’s why an upcoming meeting of international experts will meet to discuss today’s state of knowledge regarding volatiles in the lunar polar regions.

You may like

What’s missing?

“I think there are at least three aspects regarding lunar polar volatiles that we are missing,” said conference organizer, Shuai Li of the Hawaii Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

First is the need for a comprehensive survey of major volatiles possibly present in the lunar permanently shadowed regions, or PSRs. That survey is critical and missing, Li told Space.com.

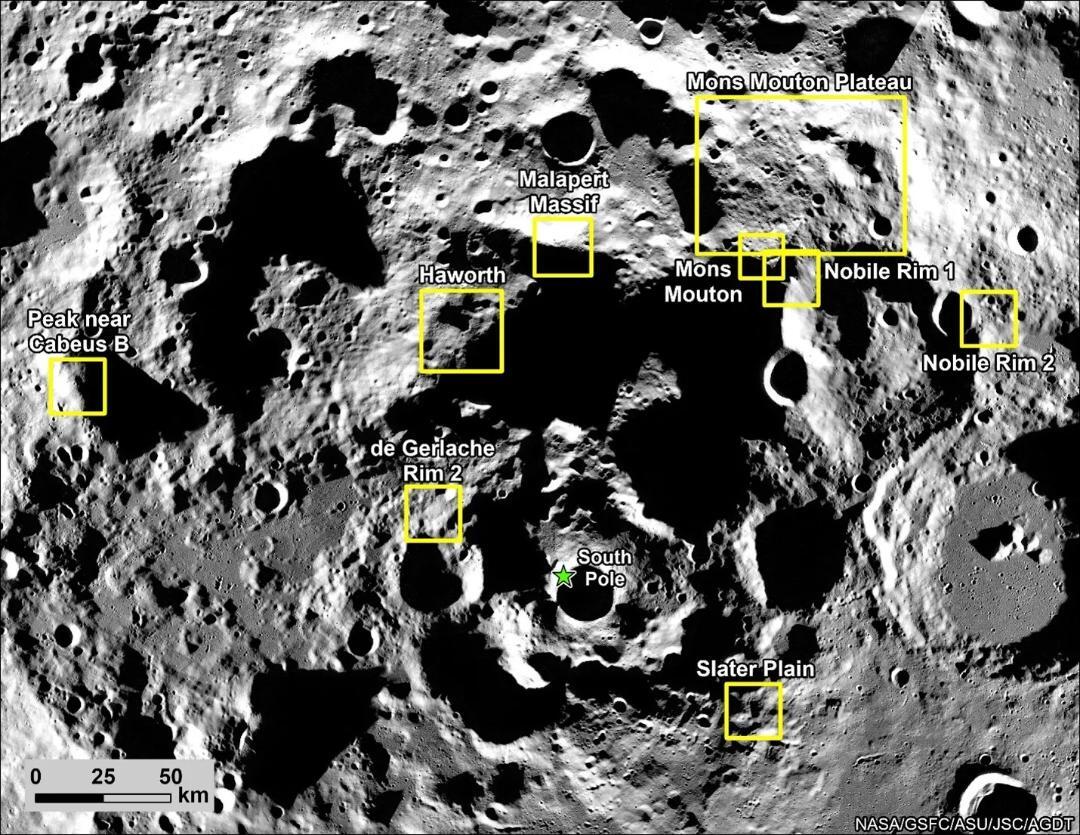

Nine candidate landing regions for NASA’s Artemis III mission The background image of the lunar South Pole terrain within the nine regions is a mosaic of LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) WAC (Wide Angle Camera) images. (Image credit: NASA)

“For instance, water ice could be the most abundant volatile but we still have no robust mapping of it, particularly at many regions that may only harbor a few weight percent, or even less water ice,” said Li. Other notable volatile species such as hydrogen sulfide, carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide could be much lower abundance than water ice.

“We do not have direct observations of such volatile species,” Li said.

Secondly, there is a lack of knowledge on how volatiles distribute vertically, including water ice.

And thirdly, said Li, is the need for sampling of those volatiles to understand their origins and how they formed and sequestered on the moon.

Just getting started

Norbert Schörghofer, senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute and resident in Honolulu, Hawaii, is a co-organizer of the upcoming gathering.

You may like

“In my view, the field of ‘lunar polar volatiles’ is just getting started,” said Schörghofer. Many missions, such as the recently reinstated Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, or VIPER, have been delayed, “and we don’t have nearly enough data to assess the abundance and distribution of water ice on the moon,” he told Space.com.

Most importantly we need definitive proof of ice on the moon, Schörghofer said.

Wanted: definitive and reproducible evidence

Back in October 2009, NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), was purposely put on a “slam dunk” trajectory to confirm the presence of water ice in a permanently shadowed crater at the lunar south pole.

“LCROSS measured six percent, but that’s not a lot of ice and it was a single-shot experiment,” said Schörghofer. “And the spectroscopic detections of ice exposed on the surface from lunar orbiters are hopelessly incoherent. We need definitive and reproducible evidence,” he told Space.com.

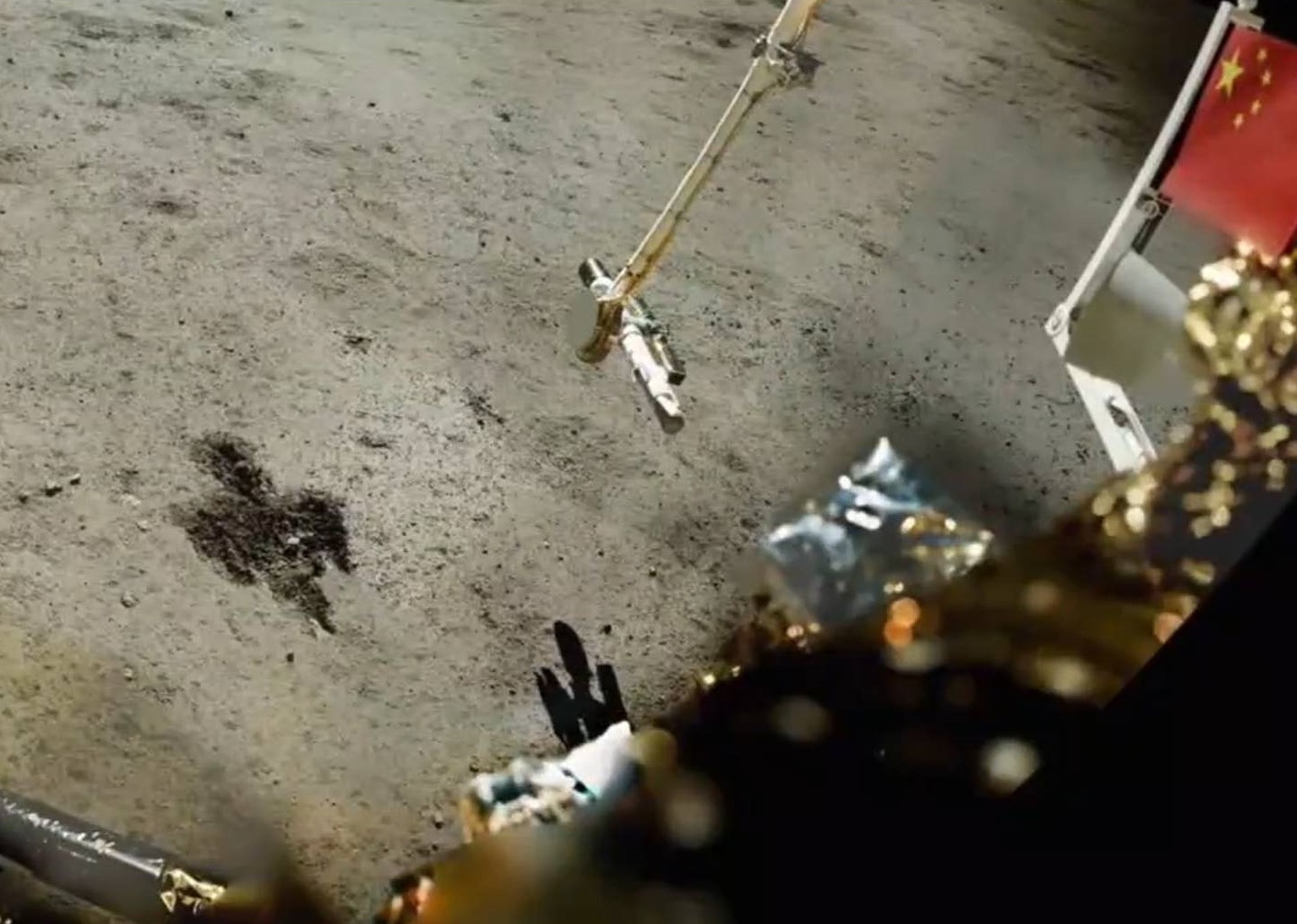

Schörghofer observed that there has been major progress regarding water inside of rocks, based on the return samples from China’s Chang’e-5 and Chang’e-6 near side and far side missions.

(Image credit: CNSA/CLEP)

“However, there has been shockingly little progress about ice, due to the lack of landed missions to the polar regions. Scientists are trying to tease out information about ice from data that were collected for other reasons, from instruments that were never designed to detect lunar volatiles, so we ended up with a lot of ‘maybe’ observations,” said Schörghofer.

International collaboration

In terms of new research by multiple nations, how is international cooperation evolving? Is there a need for more collaboration between countries?

“Very slow in progress, but we can see the growth,” responded Li.

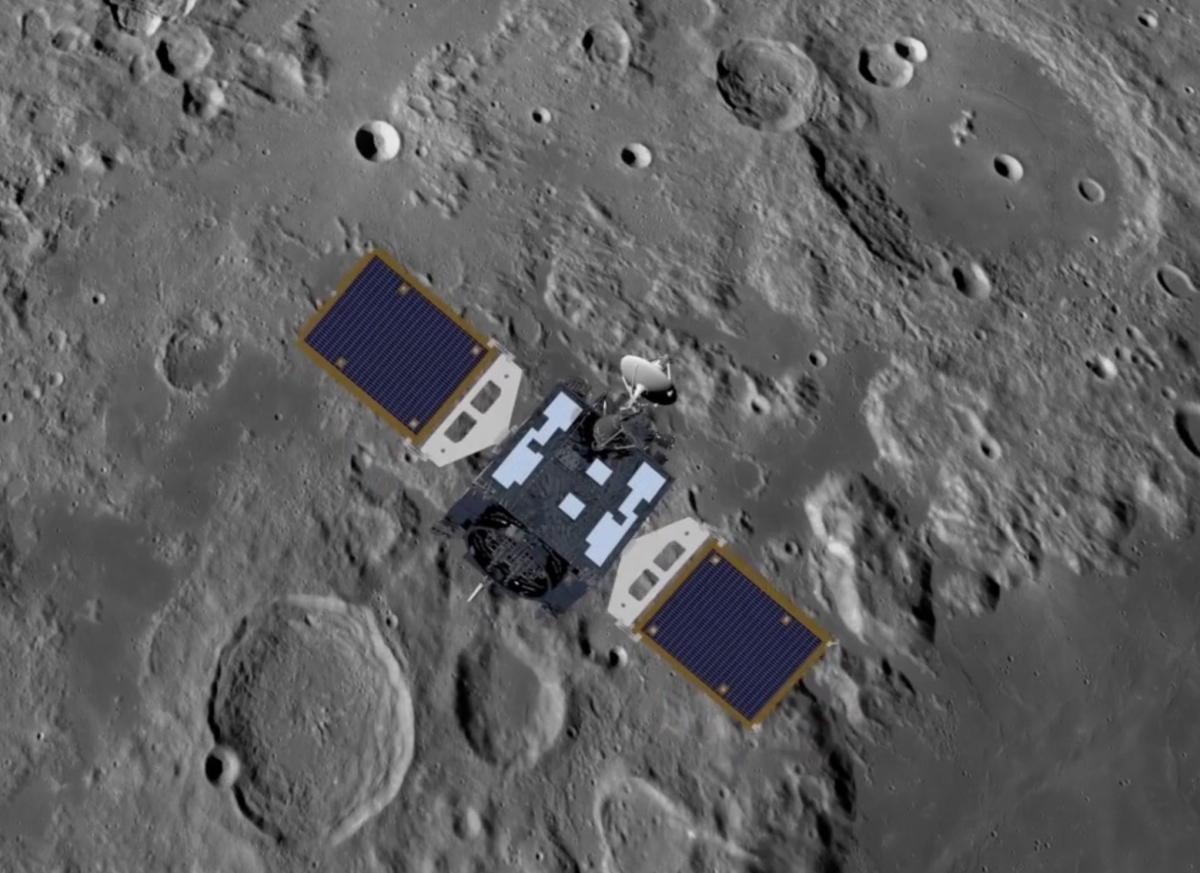

A great step in collaboration has been between the US and South Korea’s Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KPLO) called Danuri that carries ShadowCam, an ultrasensitive camera provided by NASA/Arizona State University/Malin Space Science Systems to look inside PSRs on the moon.

The Korean Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter, KPLO, is outfitted with ShadowCam instrument to look inside permanently shadowed regions, or PSRs. (Image credit: Korean Aerospace Research Institute)

Over the next decades, lunar exploration will be largely driven by the US and China, said Schörghofer.

“International collaboration is nice to have and broadens the scientific interest in the moon. The degree of cooperation will undoubtedly increase, but ultimately we are looking at a competition between two superpowers,” Schörghofer said.

Share findings

There remains a lot of uncertainty about how much ice there is on the moon, and where exactly it is.

“Reserves, in the sense of known and readily recoverable resources, are hence arguably quite small at this point of time,” Schörghofer said. “What we need is definitive measurements of the ice content,” he emphasized.

“There is definitely a need for more collaboration internationally,” Li added. “For instance, there will be many missions to the lunar south pole in the coming years. It will be super beneficial to all countries if they can share their findings about lunar volatiles, not only for science but also for in-situ resource utilization purposes,” he concluded.