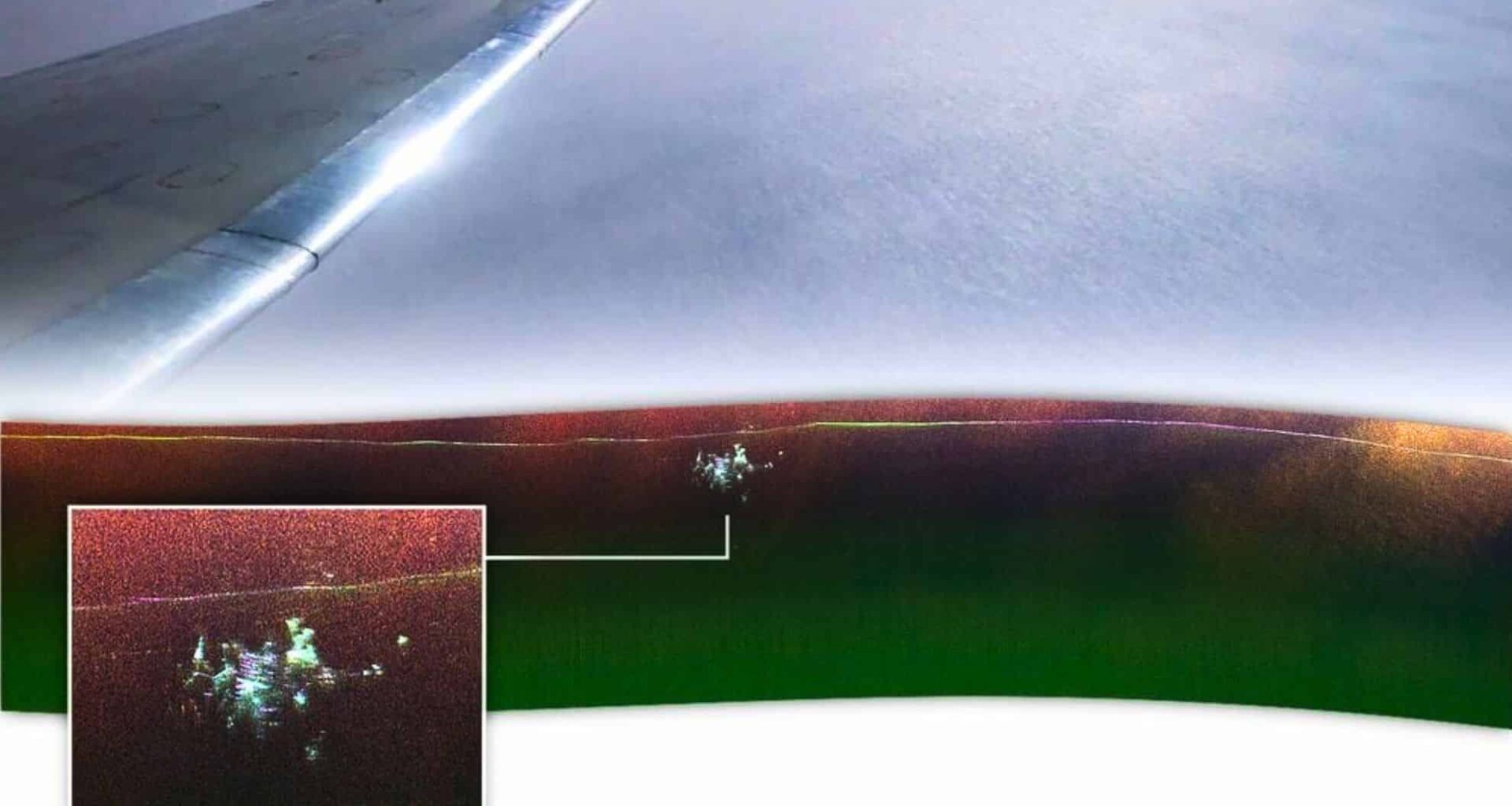

In April of this year, a NASA aircraft flew low over the remote expanse of northwest Greenland, part of a routine scientific mission to calibrate ice-penetrating radar. What the radar picked up, however, was anything but routine. Beneath more than 100 feet (30.48 m) of ice, scientists spotted ghostly outlines—parallel lines, unnaturally straight, buried deep in ancient ice. The image matched a long-abandoned U.S. military installation built in secrecy during the Cold War.

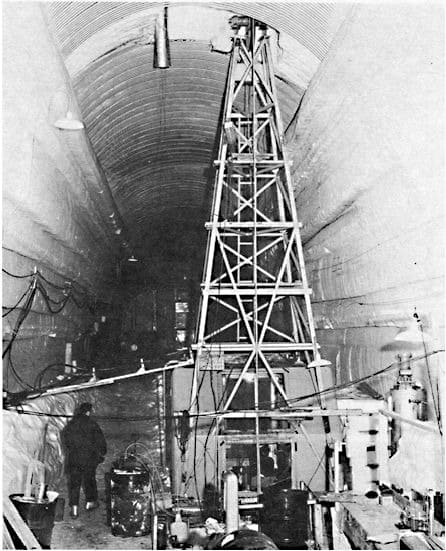

The site was Camp Century, a 1950s-era military outpost carved into the Greenland Ice Sheet by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. At the time, it was celebrated as a marvel of Arctic engineering. But beneath the headlines and scientific mission lay another agenda: Project Iceworm, a covert plan to deploy nuclear missiles in tunnels beneath the ice, aimed at the Soviet Union.

Now, more than 60 years after its decommissioning, the remnants of Camp Century are once again coming into focus—this time not as a strategic asset, but as a potential environmental liability. The Arctic, long assumed to be a deep freeze capable of preserving the camp forever, is warming faster than almost anywhere on Earth.

A Cold War Relic Frozen in Time

Constructed in 1959 and abandoned in 1967, Camp Century was built roughly 125 miles inland from Greenland’s northwest coast. At its peak, it housed over 200 military personnel and ran on a compact nuclear reactor flown in piece by piece.

The base featured tunnels, research labs, dormitories, and even a chapel—all buried beneath the snow. Its official purpose was Arctic research, but internal documents later revealed that it had been a test site for launching nuclear weapons from under the ice.

The larger-scale missile deployment plan was eventually scrapped. The tunnels were unstable, the technology was premature, and the risk of provoking Danish authorities—Greenland was, and remains, part of the Kingdom of Denmark—was considerable.

When the U.S. withdrew, the nuclear reactor was dismantled and removed. But nearly everything else was left behind: construction materials, diesel fuel, wastewater, and insulation containing toxic compounds like PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls).

At the time, military planners assumed the base would remain buried beneath accumulating snowfall forever. That assumption, it turns out, may have been dangerously optimistic.

Melting Ice, Rising Risks

Recent research by the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), a partnership between the University of Colorado Boulder and NOAA, paints a troubling picture. A 2016 study published in Geophysical Research Letters suggests that the portion of the ice sheet covering Camp Century could begin to experience net melt before the end of the century—possibly as early as the 2090s under current climate projections.

The study estimates that the site contains more than 200,000 liters of diesel fuel and 240,000 liters of wastewater, along with an unknown quantity of radioactive coolant from the former nuclear reactor. All of it could become mobile if the ice begins to melt and runoff carries contaminants into surrounding ecosystems.

NASA’s 2024 flight over the site, equipped with UAVSAR (Uninhabited Aerial Vehicle Synthetic Aperture Radar), was not intended to revisit Camp Century. But the radar’s side-looking, high-resolution imagery happened to pick up buried structures that aligned almost perfectly with historical blueprints. “We weren’t looking for it,” said Alex Gardner, a cryospheric scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “It just showed up.”

Geopolitics Meets Permafrost

While the environmental risks are serious, the legal and political questions are equally complex. At the time of construction, the United States had an agreement with Denmark to maintain military operations in Greenland. But Project Iceworm was kept secret from the Danish government, a detail that has fueled political tensions ever since its exposure in the 1990s.

Today, Greenland is a self-governing territory, and any future cleanup could raise thorny questions about liability and sovereignty. “This is a new kind of political challenge,” said lead researcher William Colgan, who co-authored the CIRES study. “Two generations ago, people buried waste in places they thought would never change. Now, climate change is rewriting the map.”

The issue isn’t confined to Greenland. Other military and industrial waste sites in Arctic permafrost—from Alaska to Siberia—may also face destabilization as global temperatures rise. But Camp Century stands out because of its scale, the presence of nuclear materials, and the secretive nature of its origins.