This article is part of The Athletic’s series marking UK Black History Month. To view the whole collection, click here.

Who are the most powerful people in British boxing?

For most, the names that would first come to mind are Frank Warren and Eddie Hearn, the leaders of two of the country’s biggest promotional companies in Queensberry and Matchroom. Earlier this year, they were the highest placed Britons on a list of the sport’s 50 most powerful figures, compiled by Boxing News magazine.

That top 50 included a mix of promoters, media executives, managers, boxers and trainers and was topped by Turki Al-Sheikh, the chairman of Saudi Arabia’s General Entertainment Authority, who has ploughed huge amounts of money into the sport in recent years.

Further down the list, at No 49 was Anthony Joshua. The former unified world heavyweight champion and 2012 Olympic gold medallist was the only Black Briton on the list.

Even allowing for the fact that this was just one publication’s verdict, and only 11 Brits made the list in total, it begs the question: given the predominance of Black fighters in boxing, why are there so few non-white faces at the top of the sport?

Answers are not easy to come by, not least because not even boxing’s governing body in Britain knows precisely what the numbers are.

The British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC) — led since 2008 by general secretary Robert Smith, a former professional boxer — has been overseeing British professional boxing since 1929 and is responsible for, among other things, granting licences to professional boxers, managers, trainers, promoters, referees, matchmakers, MCs, ringmasters and timekeepers.

Asked by The Athletic if he knows how much diversity there is among those licence holders, of which he says there are just over 3,000, Smith says he can’t give any specific numbers because they don’t keep a record of ethnicity.

“And that goes for everybody,” the 63-year-old says. “We have Black promoters, Black trainers, white promoters, white trainers, Catholics, Sikhs, Protestants – we don’t record any of that at all, it doesn’t make any difference to us.”

Smith points out that the board’s vice-chairman Guy Williamson, a former police officer and British amateur super-heavyweight champion turned barrister, is Black and adds, “We have lots of Black people on the board and on area councils around the country.”

Ultimately, though, Smith insists the BBBofC does not consider the matter a priority. “It’s something we just don’t discuss,” he adds. “If somebody wishes to apply for a promoter’s licence, anybody can do that. If somebody wants to apply for a boxing licence, anybody can do that. We don’t think it’s right that we should keep a record of where they’re from.”

Pat Barrett is a former British and European light-welterweight champion, who retired in 1994. In 2011, he was granted his licence to become a trainer and promoter by the BBBofC after a five-year wait.

Barrett suspects the reason for that delay was due to having been sentenced to three years in prison after he had been found with a loaded firearm and a quantity of heroin in 2003. After 22 months he was released, with the intention of repaying the faith of Brian Hughes, the man who had not only trained him as a fighter but had spoken in court in defence of Barrett’s character. That meant applying for his trainer’s licence.

“When I saw how tough it was getting for Brian (to keep training fighters), I wanted to be part of it to help him out,” Barrett says. “I’m not gonna lie and say I wanted it to change my life, but it naturally has changed my life, and it’s made me realise that people look up to you for what you do.”

Pat Barrett, left, celebrates with Zelfa Barrett after his super-featherweight win against Costin Ion in 2023 (James Chance/Getty Images)

After five years of meetings with a panel from his area council — one of seven which make up the BBBofC — and being repeatedly told to come back next year, Barrett returned with a solicitor who had been working with the now deceased Ricky Hatton. He left with their word that his application would be approved, on the understanding that “if I got in any kind of problems, they would revoke my licence.”

Barrett has since set up his own promotional company, Black Flash Promotions, and earlier this year was inducted into the British ex-boxers’ Hall of Fame as manager of the year. He is one of the few Black Britons to become a promoter, and arguably the most high-profile since Ambrose Mendy, who managed and advised Nigel Benn.

Barrett is conscious his chequered history has not made life as a promoter easy for him, but also wonders whether skin colour has been a major factor.

“I never looked at the racial side of it,” says Barrett. “I just thought, ‘Keep going’. It wasn’t until I stopped to think about it that I thought, ‘Wow, could you believe I was the only Black promoter at that time?’

“Trying to get people to put fighters on my show just wasn’t happening. I was getting a bad reputation before I even got going. On my own shows, it would be just six of my own fighters that would try to sell tickets. Nobody else was putting boxers on my shows. And now everybody wants to put boxers on my shows — they’re rammed.”

Barrett celebrated his 10-year anniversary as a promoter recently and says on reflection it has been one of his “toughest missions to accomplish… Even trying to get sponsors and people to back you, it’s f***ing hard.

“Nothing is easy, no matter what you try to do in life, but I didn’t realise it was the colour of my skin that made things difficult. I just thought, ‘This is the way of the sport; just keep persevering. Keep winning’.”

When asked by The Athletic for the BBBofC’s response to Barrett’s comments, Smith replied: “Pat’s application for a licence was considered and processed exactly the same as every other licence application. With regard to applications for contests, again, each and every application is considered on its own individual merits regardless of the licence holder applying.”

One of the people Barrett credits with helping him in his mission to get his trainer’s licence is Spencer Fearon. A former professional boxer, Fearon went on to become the youngest ever Black British promoter in 2007, receiving his manager, training and coaching licences at one sitting with the BBBofC. He produced eight champions over a four-year period before moving into punditry, consultancy and mentoring.

Spencer Fearon, left, with boxing writer Colin Hart in 2024 (Jeff Spicer/Getty Images)

He says that sport and entertainment have been “dominated by people that are a lot like myself” and that “it should be reflected on the other side as well”.

Fearon does believe things are starting to change.

Joshua set up his own management company, 258 Management, in 2017 and has a diverse team that includes chief operating officer David Ghansa. Promotional company Blvck Box Global is run by Dean Whyte. Elliott Amoakoh manages Chris Eubank Jr, and Michael Ofo does the same for Fabio Wardley and Dillian Whyte. In 2023, two-weight world champion Natasha Jonas became the first Black British female to become a boxing manager.

That change is also being seen on a global scale, says Fearon, pointing to the emergence of African boxing promoters including Dr Ezekiel Adamu, who is chief executive of Balmoral Group Promotions in Nigeria, and Sharaf Mahama, CEO of Legacy Rise Boxing Promotions in Ghana.

“Things are gonna change,” says Fearon, “because right now, people are running out of the pound note. Ghana has a lot of lithium and gold. Nigeria has a lot of oil; there’s money in Black countries. Seeing a prominent Black promoter will trickle down and it will ignite around the whole world.”

Racism is not a word that many people within the sport use when asked why there have been so few Black individuals in boxing’s top roles.

Jonas, who did not even realise she had made history by getting her manager’s licence two years ago, points out that it’s a similar story in other sports. “If you look at football, if you look at track and field, we might be a high percentage of the athletes, but we’re a very low percentage of the board,” she says. “I don’t know why. Maybe it’s opportunity, maybe it’s… I don’t know.”

Eddie Hearn says that, when it comes to managers, trainers and promoters, a lot of them are ex-fighters, and that opportunities are there. But he recognises that when it comes to more inward-facing industry roles, there is work to be done.

“That’s something we need to look at as a business as well,” says Hearn. “I always feel that we need to create opportunities for the best people and it’s always the argument of the background of that individual and stuff like that… I always think that you should be there on merit. I think that’s true equality.

“But I do think that in the business space there aren’t as many… I don’t know if it’s opportunities, but roles that are filled by people with that background. I don’t know the reason why. I certainly don’t think there’s an underlying stereotypical or racist element to the sport or the business at all, but it’s interesting. I think we need to provide opportunities for everybody.”

Jonas, who has not fought since her defeat to Lauren Price in a world welterweight title unification bout in March, first applied for her managers’ licence so she could take charge of her own career. Getting licensed is something she believes every boxer should do, not necessarily with the aim of managing themselves but so they are armed with knowledge that allows them to be part of the conversations which shape their futures.

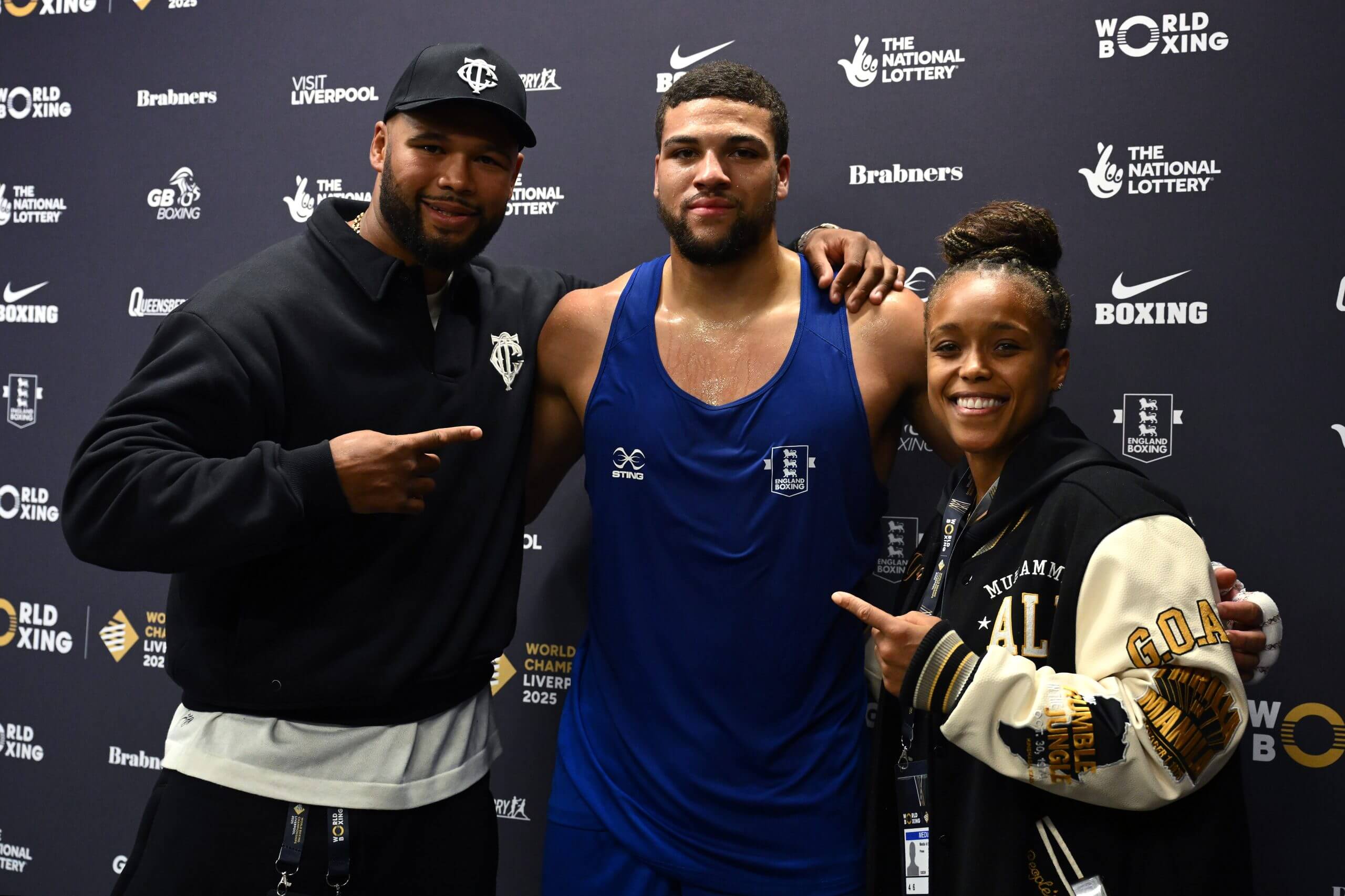

Natasha Jonas with British heavyweight Frazer Clarke, left, and Damar Thomas, centre, after the latter’s win against Myrzakir Koshaliev at the 2025 World Boxing Championships (Ben Roberts Photo/Getty Images)

Would she consider adding the title of promoter to her CV? Jonas says it was a fleeting thought when the broadcast deal between British promotional company Boxxer and Sky Sports came to an end earlier this year. What held her back? “I wouldn’t do it unless I had a certain backing,” she says. “Platforms like Sky and DAZN want to see a track record of you being successful before (signing a deal) but it’s a lot of risk to take that on if you haven’t got the right support.

“Maybe that is why people, in particular Black people, don’t go on, especially in boxing. Because they don’t necessarily have that big funding pot to begin with. Or have the contacts to be able to fund the show or to get sponsors. It costs a lot of money to begin with, and very few of us come out (of the sport) with the type of money to be able to do that.”

All of those licensed by the BBBofC pay a licence fee to the board. In addition, Smith says that promoters pay a tax for each tournament for the work done in the BBBofC office. He points out that the board, which was incorporated as a Limited Liability Company in 1989, is self-funding.

The fee for a promoter’s licence is £656 ($874) but the board also requires a bond, which could be cash or an indemnity from the bank. That bond, which is cancelled when a promoter retires, is to protect any licence holders should the promoter not fulfil their obligations. It means that if the promoter has financial difficulties with a show, the bond would be used to cover costs such as ambulance crews and boxers who haven’t received payment. The minimum bond required is £10,000. For the bigger promoters, it’s more.

The representation deficit seems clear; the pertinent question is: what can be done about it?

English professional football has a long history of falling short when it comes to off-field representation, with diversity lacking in boardrooms and among managers and head coaches. Various tactics have been employed to tackle it, the latest being the Football Association’s leadership diversity code, launched in 2020, which set hiring targets to address inequality – a version of the NFL’s Rooney Rule, introduced in 2003 and which requires teams to interview minority candidates for head coaching and other senior roles.

How effective it has been is questionable; in 2023, an FA report said workforce representation in football still did not reflect the diversity of its players.

Could boxing adopt a similar approach to improving the diversity of those in leadership roles within the sport? Smith believes it’s not necessary.

“I think we’re one of the most diverse sports there is,” he says. “Look at the boxers we have, and our managers and promoters. I think we’re very diverse. We obviously have equality training with all our staff and all our councils have to do that as a given. So we are very keen on equality etc, but to go out for a certain type of person, we think is wrong because we’re open to everybody.”

In the BBBofC head office in Wales’ capital city Cardiff, Smith says they employ 12 people, of whom one is Black. “The population of ethnic minorities throughout the country is 10 per cent? Or 15 per cent?” Smith adds (the latest UK Census in 2021 found that 18 per cent belong to a Black, Asian, mixed or other ethnic group). “It’s a majority white country and a Christian country, so we’re just resembling society.”

Smith says that the board’s seven area councils “have diversified” and contain a cross-section of society, including “ex-policemen, solicitors, tradesmen, ex-boxers. “Is there more we can do?” he asks. “Possibly, I don’t know. But are we open to absolutely anybody who shows the right enthusiasm and is qualified to do so? Yes, we are.”

Johnny Nelson, the former cruiserweight world champion who has become one of the best-known boxing pundits in the UK, says that quotas are not the answer. Instead, in his view, it’s a matter of people forcing the issue by virtue of their talent and ambition.

“We’re at a point now where if you’re going to be racist, you’ve got to be covert, got to be undercover, otherwise you’ll get called out. If you get called out, eventually the walls will close in on you,” Nelson says. “But people have got to put themselves in position to say, ‘I’m a promoter, I’ve got the fighters and I’m sitting down with a TV executive to try and get an opportunity’. Then, if everybody’s cued up and you’ve got a better Black promoter or manager with a better stable and he still doesn’t get it, that’s because he’s Black.

“You want to take away every single excuse for them. It’s like kicking the doors down, you’ve got to force change.”

It’s hard for Black promoters and managers to say that they’re not getting opportunities because they’re Black, says Nelson, because opportunities in the sport are hard to come by, no matter what your race is. He believes that when a Black promoter or manager comes along who is good at their job, the fighters and opportunities will follow, citing the example of Izzy Asif, the Sheffield-born, British-Pakistani former professional boxer who is CEO of GBM Sports, a promotional company that launched in 2022 and hosted its first world title fight in May this year (Terri Harper’s defence of her WBO lightweight title against Natalie Zimmermann in Doncaster).

“He’s got sponsorship, he’s working with DAZN, he’s chugging along,” says Nelson. “You are going to come up against prejudice and closed doors. You just have to make it impossible for them to differentiate.”

There is one person Nelson picks out as having the potential to really move the needle when it comes to Black representation at the top level of boxing: Joshua.

“I believe AJ and 258 (Management) would be a powerhouse,” he says of the suggestion the former heavyweight world champion, now 36, could move into promotion after he retires. “AJ is young, he’s got his finger on the pulse, he’s been there, done it, talks well, TV loves him. He’s the perfect ambassador.

Anthony Joshua, right, doing media work with Johnny Nelson (Richard Pelham/Getty Images)

“It would be a great opportunity to be the first Black promoter to get a mainstream TV deal because he has a structured business model set up, he’s got the staff and he’s got the fighters.

“The only reason why it’s not happening yet, I think, is because he’s an active fighter with an existing contract with a promoter.”

For Fearon, this is ultimately a story as old as time and one that, at the age of 51, he is tired of rehashing. He doesn’t even want to use the word “racism” anymore, instead describing it as “selective preferences. People favour who they favour. And who they can feel a common denominator with.”

Change will come, he says, when those with the power to spark it recognise their worth.

“Sometimes you just have to be the change that you want to see. Unfortunately, fighters who are coming through don’t realise how powerful they are,” he says. “We have to look at it and realise that anything you do is going to be difficult. If you’re a person of colour, you get one or two chances and that’s it. If you’re European, Anglo-Saxon, Caucasian, European, there’s more chances. That shouldn’t be an excuse for you not to try, though.

“As soon as somebody understands that they are the power, everything changes.”