My audition for the Smiths took place at Spirit Studios on Tariff Street in Manchester, where I was told Johnny [Marr] and his bandmates were rehearsing. Johnny looked fantastic. Intimidatingly so. He was wearing a leather coat and boots — very expensive and way out of my league. From his perfectly coiffed barnet down, this was a lad who prided himself on looking good. Johnny seemed like he’d been a guitarist since he was born. I still don’t think I’ve ever come across anyone who suited a guitar slung over his shoulder like that kid did in 1982. Even now, Johnny doesn’t play guitar; he wears it.

And then we started to play. I’d never heard anyone or anything like Johnny before. It was unique. He sounded like four guitarists at once. I’d never drummed to music like this before — it had a mystery to it. The musicians I’d worked with previously had a much more aggressive, direct, abrasive sound. Johnny was just like a f***ing orchestra, with this kid, this prodigy, conducting the whole thing. Every instrument, every sound, every plucked string, every scraped bow, every timpani roll passed through him.

• Morrissey is back — but here’s why we’ll never see a Smiths reunion

But the guy on vocals? He was definitely a bit weird. Steven [Morrissey] barely acknowledged my presence. He stalked up and down, back and forth, at the edge of the room like some pasty, skinny caged animal in a long trench coat, not saying a word. He looked up every now and again but as soon as I tried to make eye contact or shot a glance in his direction he would look down at the floor. Yep, weird.

It is easy to retrofit the significance of all of this — that first rehearsal freighted with all the weight of the band’s subsequent history, good and bad. But, truth be told, I didn’t think much more about it; it was just some awkward guy I’d just met, a singer who didn’t really say much. And a bass player [Dale Hibbert, quickly replaced by Andy Rourke] who couldn’t really play that well, but at least he talked.

This wasn’t the Smiths. This wasn’t Morrissey — we all called him Steve or Steven back then — and this wasn’t Johnny Marr. This was just these three lads.

Johnny had met the half-Irish, half-English Andy [Rourke] at St Augustine’s Catholic grammar school [in Manchester], where the two became best friends and started playing in bands together at the age of 13, most recently in the short-lived funk band Freak Party. With Johnny’s Irish Catholic roots and Morrissey’s immigrant family from Dublin, it seemed to me that these guys were the same as the kids I had known all my life. Despite often being unspoken, it was comforting. But it became increasingly apparent that Steven operated with a certain otherness to most people I had met. He could be shy and self-contained; I was, conversely, a loudmouth, talking to anyone, curious about their lives and loves. But he was just unusual. And he certainly didn’t display any interest in what Andy or I were doing.

When encountering new people he did not find it necessary to engage with anyone outside of the few individuals he deemed worthy. He would not let anyone into his world unless he specifically wanted them in it, and I did not want to pry or try to induce him to open up to me, as it was obvious that wasn’t what he wanted. It seemed the best way to conduct our relationship was for him to provide the boundaries. And the door was not open to us having a close relationship. He was barely talking to me through the letterbox.

In short, we just didn’t have that connection in those early days. I was the drummer; he was the singer. That’s it. I was comfortable with that. Andy had similar experiences with Morrissey. In the early days of the band, at the end of rehearsals Andy and Morrissey would get the bus home together. On one occasion they sat next to each other in near silence. Andy actually counted the lampposts that he saw out of the window. He just couldn’t crack Morrissey. For all of our shared ancestral heritage, it’s a miracle the band made it out of 1982, such were our apparent differences, the sense of total social dislocation from our singer and lyricist.

• Morrissey says Johnny Marr rejected ‘lucrative’ 2025 Smiths reunion offer

The dynamics changed gradually over the years. Maybe Morrissey just felt more comfortable in my presence, maybe just a bit more tolerant of our differences. But also the speed at which we found such success — and all of the trials and tribulations that go with it — deepened that bond between us. Nobody else knew what it was like.

The birth of Morrissey

We never talked about who was going to be responsible for designing the album covers. With Johnny as the main songwriter and Morrissey doing lyrics, those two had the most creative input into the band by default. We just assumed Morrissey’s role would also include the band’s visual identity. He embraced it with open arms, working alongside [the record label] Rough Trade’s art co-ordinator, Jo Slee, to create some of the most distinctive record sleeves of the decade, of all time. You can identify a Smiths album at a glance: the font, the duotone colour palette, the long-forgotten cover star. There are very few bands whose albums have that same sense of instant identity.

• The best albums of 2025 so far, from Bar Italia to Tame Impala

I don’t remember the first time I saw the sleeve art for the Hand in Glove single. It may not have been until I was holding the finished thing in my hands. But I certainly wasn’t expecting it to feature an image of a man’s arse. I mean, it is beautiful. It’s absolutely gorgeous — the silver and blue tones are stunning. Like Michelangelo’s David, you don’t think, “Oh, he’s got no strides on.” You’re just drawn to the beauty of the male form.

Morrissey on stage in 1984, waving his customary bunch of flowers

ALAMY

Over the years there has been a certain amount of historical revisionism when it comes to who and what the Smiths were — or, more specifically, Morrissey. I did an interview not long ago with the BBC. One line of inquiry probed my opinions as to what it was like to have such an overtly gay frontman on stage. It was a daft question. I didn’t think Morrissey was overtly homosexual in anything that he did. The Smiths spoke to all outsiders, whoever you were, whatever your sexual or social persuasion. It was our great strength and great attraction. And the fact I was being asked such inane questions 40 years later was tiresome and insulting and, more significantly, based on completely incorrect assumptions.

The “threat” some felt from Morrissey wasn’t down to his perceived homosexuality but rather that articulacy that came to define him, for good or bad. But from the outset and during our pomp you could never deny he knew how to give great copy. This became apparent just after our first interview in i-D magazine, a promotion for Hand in Glove, which was released in May 1983. When the journalist came to do the interview, it wasn’t with Morrissey, it was with Steven and John, Andy and Mike — just four lads from Manchester. As we were reading the story after it had been published, Johnny and Morrissey saw that the quotes we had given were attributed to the wrong people in the band. From there on in Moz requested he do any subsequent interviews on his own, which was fine by me. And next time he would be ready. He had opinions on everything and put-downs for anyone or anything who he felt had slighted him — or might do so at some point in the future. But nothing was ever off the cuff. He had spent his whole life preparing for this moment, writing his own personal manifesto, just waiting for the time and the medium to be able to share it with the world.

In June 1983, we were excited to play in Birmingham for the first time. On the drive over we were all sitting in the van. At this time we all still called our lead singer Steve, even if, professionally at least, his surname was already being more prominently used. During a lull in conversation, Steve told us, “I don’t want any of you to call me Steven any more.” He paused and looked at each of us, then continued, “From now on I just want to be called Morrissey.”

• Smiths bassist Andy Rourke dies aged 59

If it had been me asking for a sudden change in what my mates called me, I might have been a bit more forthcoming. You know, something like, “I have always hated the name Michael and I would much rather just be called Joyce. Let’s just try that, lads.” But Morrissey didn’t give any explanation; I don’t think he ever felt he had to give an explanation about anything if he didn’t want to. It was probably always part of that manifesto of his. But ultimately we just carried on smoking and listening to music.

The Smiths’ debut single, Hand in Glove (1983)

ALAMY

The fallout

A few months after we finished recording Meat Is Murder in early 1985, I got a phone call out of the blue from Martha Defoe at Rough Trade. “I’ve been speaking to Morrissey,” she said, “and we think that your percentage should go down from a quarter share to 15 per cent.”

I was dumbfounded. “Why?”

“For a start, you’re not doing any interviews,” she stated. “Morrissey’s writing the words to the songs . . . And he’s doing all the sleeves.”

I said, “Well, I’ll do some of the interviews then.” There was silence on the other end of the phone.

I put the phone down, called Morrissey straight away and told him clearly, “There’s no way I’m going to accept that idea. Are you mad?”

Not a sound. “You don’t want to talk about this or even discuss it, do you?”

There was no reply, so there was nothing else to say. I decided to draw a line under it. The subject was never revisited and, as such, I assumed my percentage remained the same.

• Read music reviews, interviews and guides on what to listen to next

[In March 1989 Joyce began legal proceedings against Morrissey and Johnny Marr. He argued that he was entitled to a 25 per cent share of all non-songwriting profits based on the assertion that all four members were equal partners in the Smiths. In December 1996 the case reached the High Court. Joyce’s barrister, Nigel Davis QC, stated that “it was not until after the band split up in 1987 that his client discovered he was getting only 10 per cent of the profits”. The judge ruled in favour of Joyce, declaring that he was entitled to 25 per cent of profits with immediate effect, and a back payment of approximately £1 million was awarded. In late 1998 Morrissey staged an appeal that was rejected by the Court of Appeal.]

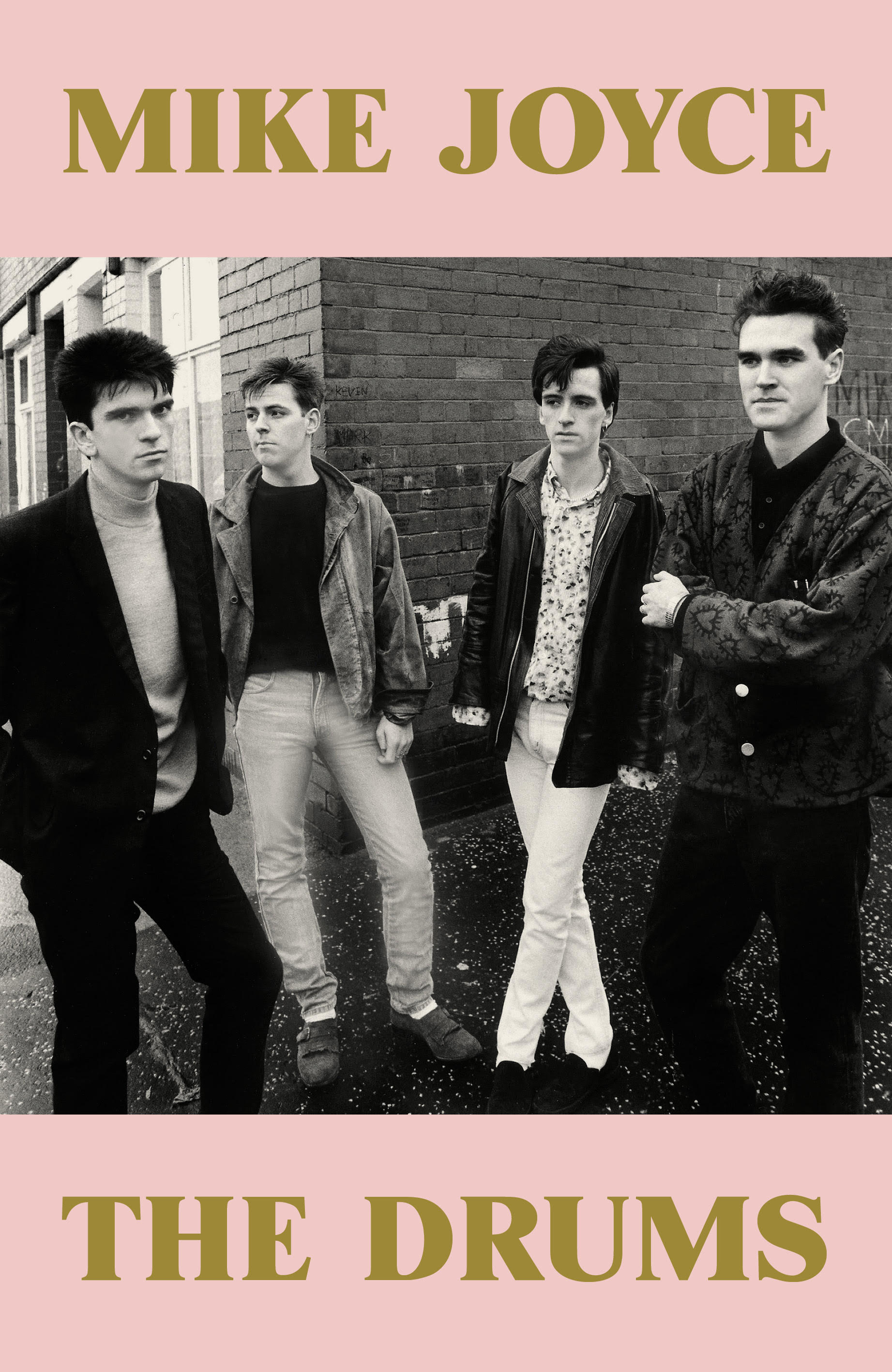

Joyce’s book will be released on November 6

When Morrissey couldn’t tell someone difficult news, it wasn’t out of laziness or arrogance. I just think he genuinely couldn’t do it. It wasn’t cowardice; it was almost like a physical block. It reminded me of soldiers in the First World War who froze in fear in the face of conflict. I also think it’s why he leant so heavily on his use of the fax machine or postcards and letters to friends — or enemies. It removed the need for any real face-to-face or verbal communication. He has a tolerance for the human race that is complicated.

Johnny, Andy and I had all grown up in wide social circles with mates and girlfriends. Morrissey didn’t have that. The band became his gang and when that dynamic was threatened in any way, he clung to it with everything he had, even if he came close to suffocating it. It wasn’t just a career to him — it was salvation.

But that same fragility is why his lyrics have endured. They weren’t crafted for effect; they were real. He wrote about feeling left out, about not being able to go out, of standing at a club watching everyone else have fun while he felt miserable and alone.

• Pop review: The Smiths: The Queen is Dead

He didn’t talk about these feelings openly — he sang them. He turned internal pain into something poetic and shared it with the world. And in doing so he found his people, who responded in more than kind. He found his disciples, both holding a mirror to each other.

Morrissey’s onstage persona was dramatic and theatrical, which was the opposite of his nature off stage. Cutting all ties to the name, for “Steven” to become “Morrissey”, was an act of reinvention.

The great Peter Sellers once remarked, “I could never be myself. You see, there is no me, I do not exist.” Steven no longer existed. To call Morrissey complex is an understatement. Yet he remains one of our truly great singers. There is a purity to his creative vision that is unparalleled.

Extracted from The Drums by Mike Joyce, to be published by New Modern on Nov 6 (£25)