John Hughes’s Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is a great example of a film where the reputed hero is actually the villain. Though it’s Hughes’s finest moment as a writer and director, the film still takes for granted its upper-middle-class teen hero’s ownership of everyone and everything around him. Beneath the film’s stylistic swipes from the French New Wave is the very personification of American entitlement.

John Hughes’s Ferris Bueller’s Day Off is a great example of a film where the reputed hero is actually the villain. Though it’s Hughes’s finest moment as a writer and director, the film still takes for granted its upper-middle-class teen hero’s ownership of everyone and everything around him. Beneath the film’s stylistic swipes from the French New Wave is the very personification of American entitlement.

It’s a bridge too far to suggest that Hughes’s earlier smash, The Breakfast Club, is the inverse of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, or to call it a film wherein the supposed villain actually turns out to be the hero. Paul Gleason’s autocratic Assistant Principal Vernon lords over the film’s quintet of niche-filling teenage protagonists, who are spending Saturday serving detention, with all the subtlety of Strother Martin playing Cool Hand Luke’s sneering prison warden. And yet, that he assigns the jock, the prom queen, the nerd, the bully, and the space cadet to write a thousand words about who they believe they are suggests he’s as concerned for the inner turmoil of the adolescent set as the film’s club members are themselves.

The quintessential Brat Pack vehicle, hampered by Hughes’s willingness to pigeonhole his protagonists in the same way as they accuse Vernon of doing, The Breakfast Club is hopelessly tethered to its era in ways that another blockbuster from 1985, Back to the Future, isn’t. And that film’s entire subtext mirrors the ’80s against the similarly regressive ’50s. Robert Zemeckis’s jaunty contraption arguably offers more cross-generational insight at any given moment than every incident of Vernon and Judd Nelson’s Bender sparring combined.

It’s not just the totally to-the-max duds or Hughes’s fixation on stacking his soundtrack with college-radio needle-drop cues. Rather, the film’s characters operate within or, in unfortunate cases like Anthony Michael Hall’s Brian, fight in vain against a disagreeably Reagan-era social context that finds young suburban Americans unsure about any number of things about themselves—except that their struggles are truly the only thing in the world that matters.

And, in true Reagan-esque fashion, the film gets away with it. Rather than writing essays, Bender, Brian, Andy (Emilio Estevez), Claire (Molly Ringwald), and, when she’s not tossing lunch meat around the room, Allison (Ally Sheedy) spend their detention snarling in the face of authority, breaking in and out of the school library (and one closet), smoking pot, letting their hair down, indulging in leftfield dance montages, and crying together. Hughes intended for this feature-length bonding session to break down whatever bullshit high-school barriers his characters perceived to be keeping them in their societal silos, which might have been an admirable goal if he managed to take it to its logical endpoint and if the elimination of said silos also led to the eradication of their accompanying power dynamics.

But even though The Breakfast Club abounds in soul-bearing moments throughout, it’s only after the popular Claire gives Allison, the unpolished diamond, a mall makeover that Andy, the big man on campus, realizes that she’s dateable. Then, everyone gangs up on Brian, the meek one, to write their “collective” essay, which he obliges while everyone else is having their bittersweet and sorrowful partings in the outside world, raising a triumphant fist to the accompaniment of Simple Minds’s “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” while everyone forgets about the geek they conned into doing their homework for them.

Image/Sound

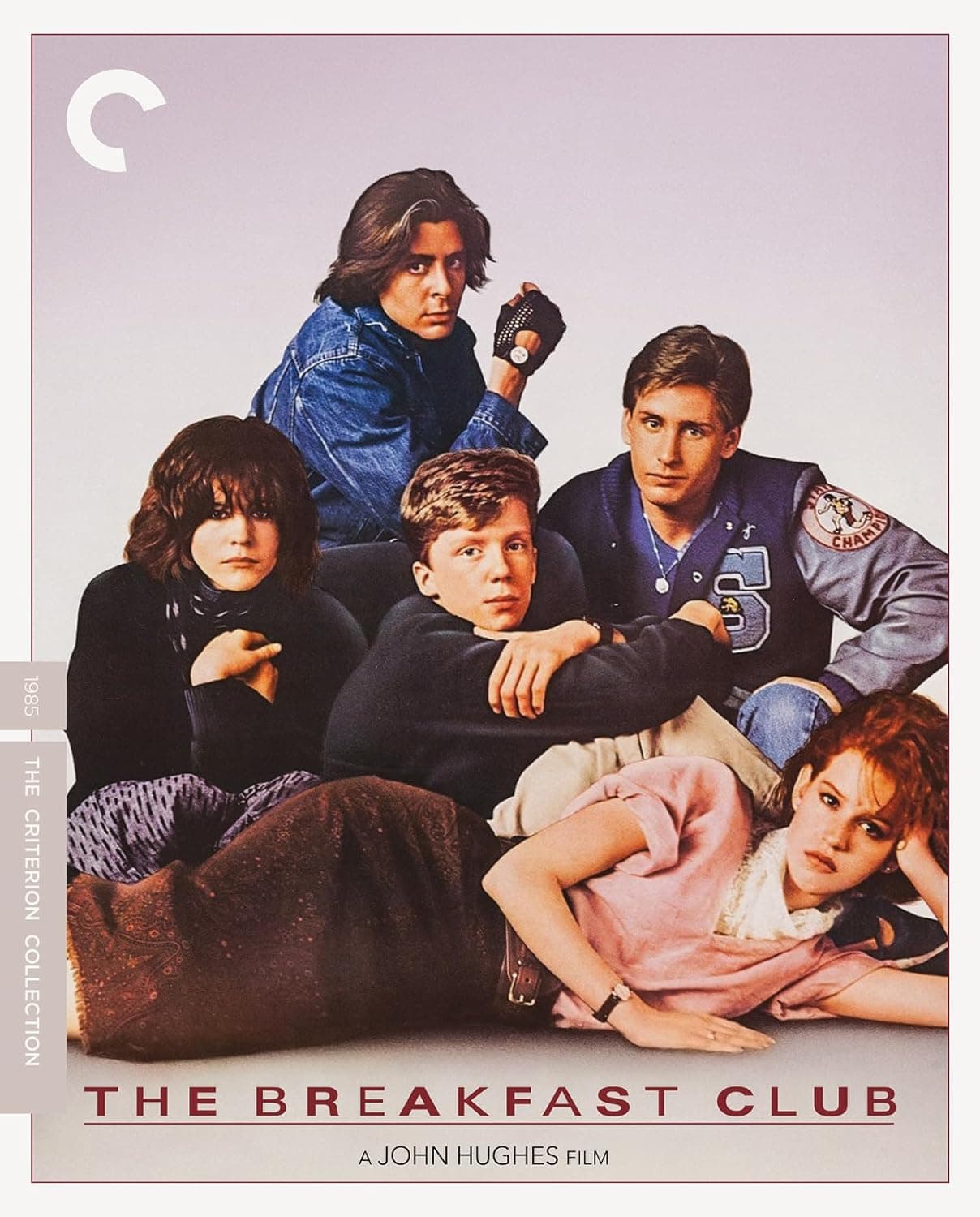

John Hughes’s sophomore effort was no high-budget affair, and its gauzy 1980s pallor endures throughout, to the extent that fans would care. While there’s a friendly, filmic look to the new 4K transfer, it’s also alluringly soft, even downright Love’s Baby Soft. The cerulean beams of the school library’s neon-lit second floor balconies provide an appealing contrast to the room’s maple paneling and redhead Molly Ringwald’s clashing pinks. The sound options are twofold: the original (and serviceable) monaural soundtrack and the 5.1 remix, which doesn’t really offer much in the way of difference aside from blowing out those accursed music cues.

Extras

The audio commentary from Anthony Michael Hall and Judd Nelson is ported over from an earlier Universal release, and it’s nice enough, though one wishes Criterion would’ve tried to get Ringwald, Emilio Estevez, and Ally Sheedy into a room for a counterpoint. The other retread is the nearly hour-long documentary retrospective “Sincerely Yours,” which includes not only cast and crew members, but jeremiads from Hughes contemporaries like Amy Heckerling.

The remainder of the extras have been ported over from Criterion’s 2018 Blu-ray release. Masochists can catch an extra hour or so of the film via the disc’s collection of deleted and extended scenes. And those still lighting a candle for the departed Hughes will be happy to bask in a 1985 AFI seminar clip with the writer-director, as well as a very Chicago-centric 1999 radio interview, and Judd Nelson’s recitations from Hughes’s production journal for the film. Finally, a brave essay by David Kamp is included in the disc’s accompanying booklet.

Overall

Forty years young, John Hughes’s sophomore effort gets a lovely new restoration, but the recycled extras on this release may leave fans of the film feeling as if they’re stuck in detention.

Score:

Cast: Emilio Estevez, Paul Gleason, Anthony Michael Hall, John Kapelos, Judd Nelson, Molly Ringwald, Ally Sheedy, Perry Crawford, Mary Christian, Ron Dean, Tim Gamble, Fran Gargano, Mercedes Hall Director: John Hughes Screenwriter: John Hughes Distributor: The Criterion Collection Running Time: 97 min Rating: R Year: 1985 Release Date: November 4, 2025 Buy: Video

If you can, please consider supporting Slant Magazine.

Since 2001, we’ve brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.