IT’S amazing how quickly things happen now.

Photographers with high-end cameras can have pictures cropped, levelled and fired off via email or WhatsApp within seconds, without even having to leave the discomfort of their pitchside perch.

The days of lumping gear up flights of stairs before wearily wading through hundreds of images on a laptop may not quite be at an end, but it’s getting there. Because lightning-fast cameras, AI and mobile technology have transformed the field of sports photography, and sports coverage.

During a post-round press conference at The Open back in July, American golfer Bryson DeChambeau was asked what he thought of the use of Spidercam technology at Royal Portrush.

Suspended above the 18th green, it offered spectacular aerial views and unique angles that “bring to life the natural undulations of the hole and short shots around the green before the greatest walk in golf is captured”.

I was up and down that course across four days, spending a fair bit of time at the 18th, particularly as Scottie Scheffler put the show to bed, and did not notice Spidercam once. Either did Bryson. That’s how sophisticated, how unobtrusive technology has become.

It is a far cry from when Brendan Murphy first picked up a camera in the early 1970s – a Zenith B, “the best camera £22 could buy”.

“It felt like a chunky metal box,” he wrote in his 2003 book, Eyewitness, “perhaps because it was a chunky metal box.

“Today’s auto-focus systems would have seemed like science fiction… but to me it possessed all the sophisticated technology that put man on the moon.”

And so, having decided to stop pulling pints – he ran Murphy’s bar, in Albert Street off the Falls Road – and beaten the demons that crept up courtesy of his chosen profession, Brendan threw himself headfirst into a new career.

It was wing and a prayer type stuff, based largely on conversations with reporters and studying the portfolios of photographers who had frequented Murphy’s through the years.

But this is where being a perfectionist helps when it comes to mastering any craft, because Brendan wouldn’t be beat.

“I wanted to prove those people wrong who put me down,” he wrote, “after the alcohol, I had a second chance and wanted to be a success.”

Thanks to the guiding hand of mentors along the way, allied to his own understanding of people and, crucially, place as the Troubles erupted on the streets that surrounded him, Brendan Murphy became a success.

As picture editor of The Irish News, he was one of the main chroniclers of the horrors that befell the north. Yet there was so much more too.

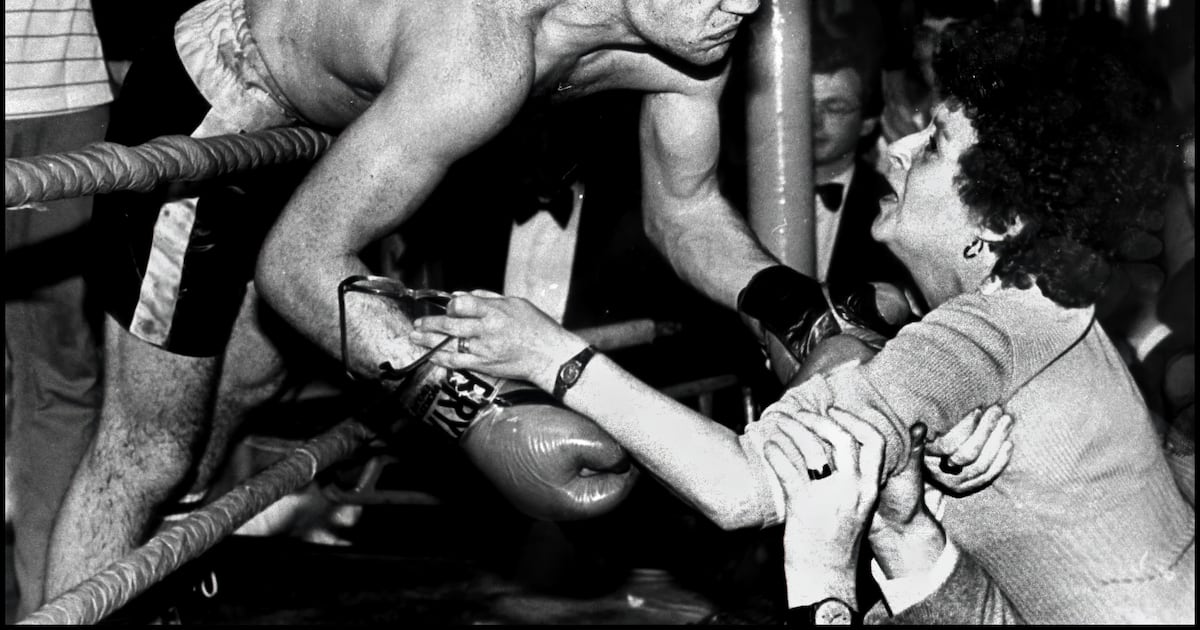

Because the image that comes to mind whenever I hear Brendan Murphy’s name is of his photographic protégé – the late, great Hugh Russell – leaning through the ropes to kiss his mother after a brutal 12-round war with Belfast rival Davy Larmour.

“Love and relief, mingled with tears and horror, were etched into Eileen’s face. Murphy pressed the shutter just before they kissed,” wrote renowned boxing writer, Donald McRae, “his black-and-white photograph distilled boxing’s gory drama and bruising intimacy.”

Brendan Murphy caotured the famous image of a British army helicopter flying over Crossmaglen Rangers’ ground during a 1986 Ulster club championship match. PICTURE: Brendan Murphy

Brendan Murphy caotured the famous image of a British army helicopter flying over Crossmaglen Rangers’ ground during a 1986 Ulster club championship match. PICTURE: Brendan Murphy

Such moments are not captured by accident, and it is the process then that becomes almost as intriguing as the outcome.

Because Brendan wouldn’t have known for sure if he had nailed the shot. He might have hoped, and prayed, but in an entirely different age of photographic processing, and shutter speeds light years from where we now stand, certainty did not exist.

Take one of the most famous sporting pictures ever snapped; of Cleveland Williams flat on his back on the canvas, having been sent there by Muhammad Ali.

Neil Leifer photographed 35 of Ali’s fights, and also captured the famous image of ‘The Greatest’ imploring Sonny Liston to get up after being floored in the first round of their 1965 world title fight.

That time he was stationed at ringside but, for the Williams fight the following year, Leifer rigged a remote camera to the lights 80 feet above the squared circle inside the Houston Astrodome.

Decades before drones revolutionised the way sports events are photographed, this was high risk, high reward. And when Williams hit the deck for the final time, Leifer hit the shutter.

“I gambled that there would be a good knockout,” he told The Guardian in 2020.

“Sometimes a fighter crumples on their chest or falls into the ropes, but Williams landed flat on his back. I knew it happened in a good spot but I didn’t have a clue how it would turn out until the film was developed.

“I remember seeing this photo come out like it was yesterday. It was still wet, heading for the drying machine, but even then I knew it was special.”

The result was a picture that perfectly captured a magic moment and, in doing so, said more than any amount of words ever could. The same applies to Brendan Murphy’s shot of Hugh and Eileen Russell.

Boxing had been a cornerstone of conversation in his days behind the bar, the thrills and spills of shows at the Ulster Hall and the King Hall making heroes of men who only ever saw themselves as ordinary Joes outside the ropes.

It was Brendan’s appreciation for their endeavour that informed his intuition on nights like October 5, 1982, as well as so many others.

That’s why, for all that the rapid evolution of technology alters the photographic landscape, so many of the same principles remain. The man himself summed it up when I asked him about the Russell picture a few years back.

“Right place, right time,” he said with a low chuckle.

Brendan Murphy retired as picture editor of The Irish News in 2003 but, on regular freelance shifts until the late Noughties, would often visit the sports department at the back of the paper’s old Donegall Street home.

Yet, barring the odd fleeting interaction, I cannot claim to have known Brendan – other than the way so many of us know him, and the way future generations will, in time, know him.

Through his pictures.