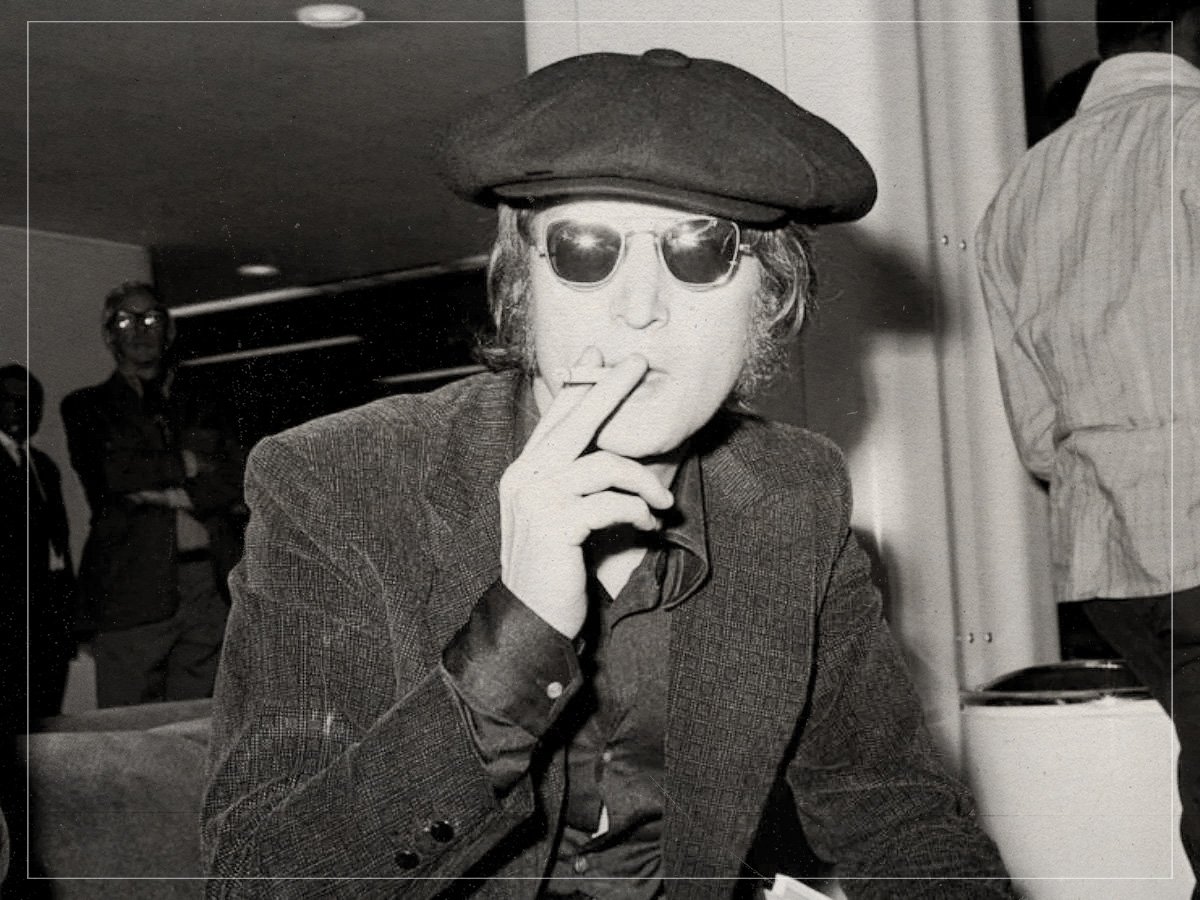

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy)

Sat 15 November 2025 10:48, UK

Mastering the art of recording in the studio is a near-impossible task for a perfectionist like John Lennon, who was always picking holes within his own work.

In the mind of Lennon, more often than not, there was always something to improve, which meant he, on countless occasions, spent far too much time in the studio. During his time in The Beatles, they could be found working through the night in search of capturing the perfect take, which they always believed was waiting around the corner.

Once The Beatles came to an end, that mindset which had spurred them to greatness remained in Lennon and proved impossible to shake. As his songs were often of an incredibly personal nature, he put a burden on himself to do these songs justice and ensure the studio recordings match the seismic emotion attached to the lyrics.

From the Freudian essence of The White Album highlight ‘Julia’ to the John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band staple ‘Mother’, tracks such as these offer insight into the inner workings of one of the most significant songwriters of all time, who, naturally, happened to be a profoundly complex individual.

A perfect example of this is ‘Working Class Hero’, also found on Plastic Ono Band, his first record since the split of The Beatles. Lennon would later describe it as a “revolutionary” song about working-class people being “processed” into the middle classes, and kicking out at the establishment, which was a favoured pastime for the singer-songwriter.

Notably, just three days before his December 1980 murder, Lennon spoke to Rolling Stone in his final interview and reflected on the meaning behind the song, sharing, “I’ve been successful as an artist, and have been happy and unhappy, and I’ve been unknown in Liverpool or Hamburg and been happy and unhappy. But what Yoko’s taught me is what the real success is – the success of my personality, the success of my relationship with her and the child, my relationship with the world… and to be happy when I wake up. It has nothing to do with rock machinery or not rock machinery.”

It was a track that Lennon deeply cared for, which was proved by the amount of work he put into getting it right in the studio. According to the tape operator Andy Stephens at EMI Studios, London, the track took over 120 takes, which made the famously irate vocalist increasingly angry. Stephens told Uncut in 2010 that Lennon obsessed over the song day after day and recorded “an endless number of takes… well over 100.. Probably 120, 130.”

“If the mix in his headphones wasn’t exactly what he wanted, he would take them off and slam them into the wall,” he continued. “He wouldn’t say, ‘Can I have a bit more guitar?’ He would literally rip the cans off his head and smash them into the wall, then walk out of the studio.”

While Lennon had a gift for songwriting, which can’t be taught, he also had a strong work ethic, which pushed him to the limit. Recording more than 120 takes of a single track in one day was unnecessary, but it shows the level of determination that existed within Lennon and the care that he had for craft. Although most would likely have decided to abort the project after a dozen or so takes that didn’t feel right and return to it another day, that simply wasn’t in his DNA.

Related Topics