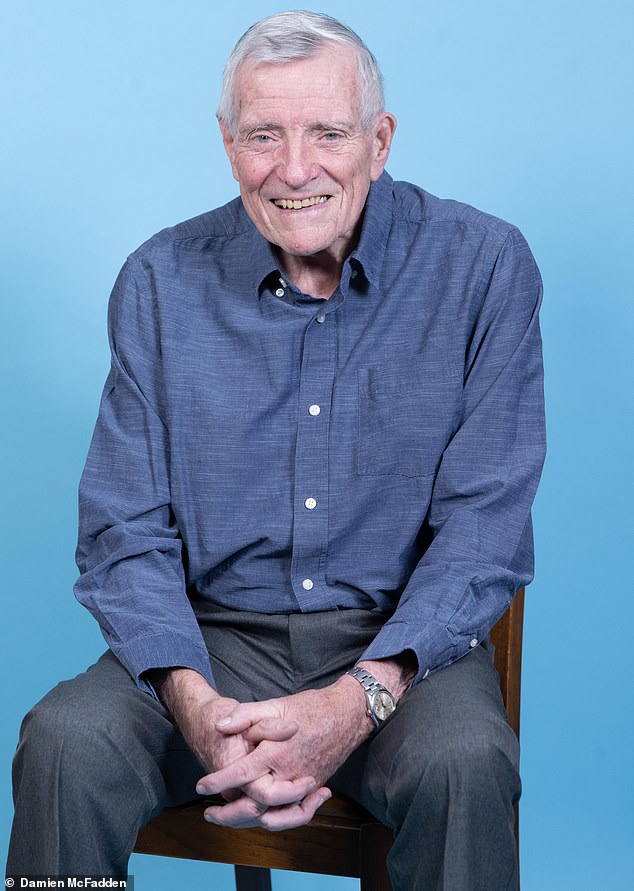

Told he had liver cancer, Roger Jackson feared the worst. ‘I thought, “Here we go, I’m going to die”,’ says the 80-year-old great-grandfather and retired sales manager.

Patients in Roger’s situation usually face gruelling surgery or chemotherapy. Instead, he became the first person in Europe to have a new, non-invasive procedure called histotripsy. The treatment uses focused ultrasound waves to break down tumours.

Without any surgical incision or the use of heat or radiation, there is less risk of complications than with conventional treatment, and no long recovery.

Roger’s liver cancer diagnosis, in July, came after an abnormality was spotted on a routine scan.

He’d been having annual liver scans and blood tests for about ten years after early signs of cirrhosis – long-term damage to the liver, often caused by drinking alcohol or as the result of a viral infection – had been discovered.

‘It came as a shock as I had no symptoms,’ recalls Roger, who lives in Bedford with his wife, Gill, 79. ‘I probably drank too much alcohol – my usual tipple was a good glass of wine,’ he admits.

A week after the latest scan raised concerns, a biopsy revealed he had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) – liver cancer. The tumour was 2cm in size.

In August, Roger met Dr Teik Choon See, a consultant interventional radiologist at Cambridge University NHS Foundation Trust – who told Roger his options included standard ablation or the pioneering histotripsy treatment. ‘As there was no surgery involved, it really appealed,’ says Roger.

When Roger Jackson, an 80-year-old great-grandfather and retired sales manager, was told by his doctor that he had liver cancer, he feared the worst

The number of Britons dying from liver cancer has risen over the past decade, according to new figures from Liver Cancer UK – around 6,000 annually.

Professor Stephen Ryder, a consultant hepatologist at Nottingham Hospitals NHS Trust, says the 41 per cent rise in deaths from liver cancer in England and Wales between 2013 and 2024 is possibly down to ‘an increase in alcohol-related liver injury – made worse over the pandemic – and a rise in fatty liver disease, due to two-thirds of the population being overweight’.

‘Chronic damage to the liver cells leads to liver scarring,’ says Professor Ryder. Scar tissue can eventually distort the liver –known as cirrhosis. He explains: ‘Around 90 per cent of liver cancer develops in people who already have cirrhosis.’

Treatment options include surgery to remove part of the liver, or a liver transplant. But this can lead to delays – according to the NHS, the average wait for a liver is five to seven months. This invasive surgery is also high risk.

A minimally invasive alternative is thermal ablation, using heat to kill cancerous cells, under general anaesthetic, with patients usually staying in hospital overnight. Recovery takes about a week.

But as it involves making a small incision, there is a risk of infection, bleeding or damage to surrounding blood vessels.

Histotripsy could reduce these risks and a patient can resume their normal life immediately.

Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge (where Roger was referred as it was his closest major liver unit) became the first UK hospital to offer histotripsy in October after the device was funded by a charitable donation.

John became the first person in Europe to have a new, non-invasive procedure called histotripsy, a treatment that uses focused ultrasound waves to break down tumours

Under a scheme overseen by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, early access can be granted for treatment with certain medical devices prior to full approval.

Developed by a US-based medical company, histotripsy has been used to treat more than 2,000 patients with liver cancer in clinical trials.

A 2025 study in the Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, involving 295 patients at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, who underwent histotripsy to treat liver tumours, concluded it was safe, with few complications and compared well with other surgical treatment of liver tumours. (There isn’t yet long-term data on success rates.)

Roger was a good candidate for the new treatment, says Dr See. ‘We could see the tumour clearly under ultrasound so we could target it accurately.’

Patients are given a general anaesthetic so they stay still during treatment. Then a special water bath containing ‘degassed’ water (meaning most of the air has been removed) is placed on the patient’s abdomen above their liver. (Ultrasound waves are more accurate when travelling through a medium such as water.)

The duration of treatment depends on the tumour type and size – Roger’s procedure took 20 minutes compared to at least one hour for ablation, and two to six hours for surgery. Dr See explains: ‘The targeted sound waves create microscopic bubbles in the liquid within the tissue around the cancer cells.

‘This mass of bubbles form and collapse thousands of times and, in effect, explode, which then destroys the cancer. But the surrounding tissue is unharmed. The cancer cells are liquefied and absorbed into the body over the next month or two, leaving a small scar on the liver.’

Consultant hepatologist Professor Stephen Ryder says the rise in deaths from liver cancer is possibly down to ‘an increase in alcohol-related liver injury – made worse over the pandemic – and a rise in fatty liver disease, due to two-thirds of the population being overweight’

He continues: ‘If this treatment didn’t go well because the of inaccurate targeting of the tumour, or it was too big, it would not stop a patient then having ablation.’ (It’s not possible to have ablation first, as the heat changes the structures of the cancer and nearby cells, making it difficult to distinguish what needs destroying.)

A second UK patient is now due to be treated using histotripsy later this month.

At present, histotripsy can only be used on liver cancers. However, trials are under way in the US assessing its feasibility for treating pancreatic cancer.

Commenting on histotripsy, Professor Ryder says: ‘Potentially it’s a very interesting treatment because it doesn’t involve external trauma.

‘There are still lots of questions to answer. For example, we still need to know how big an area of cancer can be targeted and if the long-term outcomes are as good as ablation. But it’s promising.’

A CT scan the day after Roger’s procedure showed a mark on his liver where the ultrasound was directed, but no signs of cancer.

‘I had no symptoms or discomfort beforehand and none afterwards, so in many ways it felt as if nothing had happened,’ he says.

‘I’ll go back for regular checks, but I don’t need to take any medication. I’m so grateful I could have it – I was luckily in the right place at the right time.’