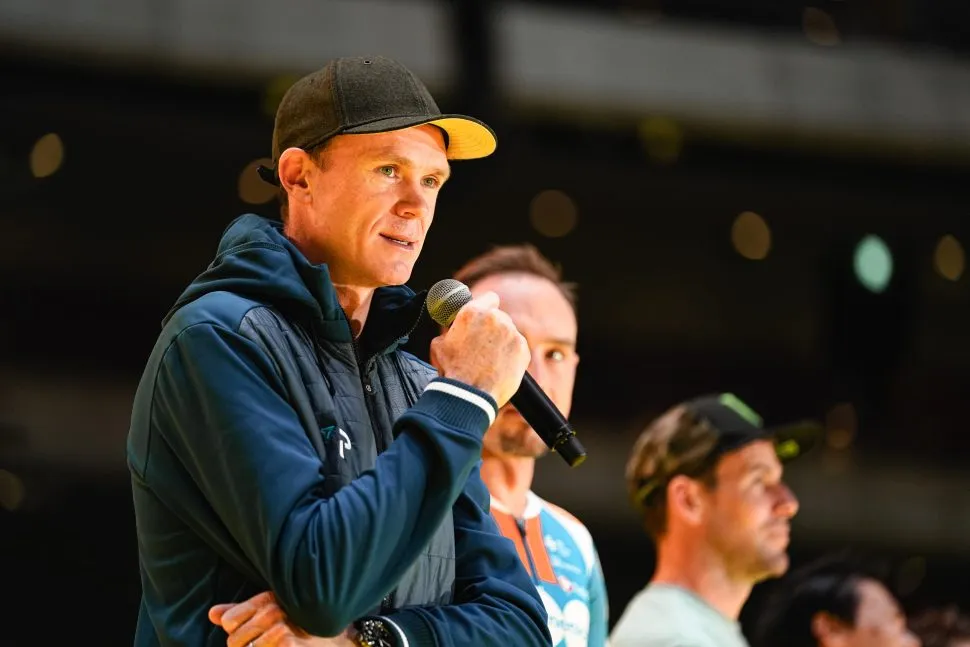

Four-time Tour de France champion Chris Froome is about to enter retirement, with few of the bells and whistles usually owed to Grand Tour champions when they bow out. His cycling requiem was never quite sung in 2025, but the end seems nigh for the man who continues to be Britain’s most successful Grand Tour rider in history.

This follows a silent breakup from Israel-Premier Tech as they begin their realignment as NSN Cycling Team, a Swiss-backed outfit that has picked up Sylvan Adams’ WorldTour licence after a tumultuous demise during the latter part of the 2025 season. Before the squad officially rebranded, they bid farewell to Froome, who was writ large on the list of departures ahead of the 2026 reset.

If this is to be the end of Froome’s pro cycling career, what will his legacy be? We’ve weighed up his impact on the sport, his role in British cycling, and what he leaves behind in the peloton seven Grand Tour victories and an 18-year career later.

Related questions you can explore with Ask Cyclist, our AI search engine. If you would like to ask your own question you just need to , or subscribe.

If you would like to ask your own question you just need to , or subscribe.

A late bloomer

ASO

ASO

Chris Froome wasn’t exactly the teen sensation we’ve been accustomed to in this era of Tadej Pogačar, Remco Evenepoel and Isaac del Toro. Instead, Froome was a Kenyan rider known for a clumsy coming-together with a UCI commissaire during the under-23 time-trial at the 2006 UCI World Championships. Despite this, future Team Sky boss Dave Brailsford would earmark him as ‘a bit of a diamond in the rough’, and that’s not because he forged emails to the UCI to enter the championships in the first place.

He pledged sporting allegiance to Great Britain the following year, and was fielded in a couple of Grand Tours as part of the Barloworld squad. Once Team Sky was formed in 2010, Froome would be nursed under Brailsford’s wings until his surprise breakthrough at the 2011 Vuelta a España, which came after a long bout with the tropical disease schistosomiasis. A surprise given he hadn’t reached the top ten of a WorldTour stage race to that point before finding himself in the fray for a Grand Tour title alongside Bradley Wiggins.

Despite the schistosomiasis explanation, plenty were shocked by Froome’s sudden arrival. However, he would later prove that he was no one-hit wonder during 2012, where he would ‘support’ Wiggins to a first British yellow jersey win, with a stage win and podium finish of Froome’s own making along the way.

I’ll go ahead and make a bold claim now. If runner-up Froome had won the 2012 Tour de France – and he clearly looked the stronger of the Team Sky pair – discussions over his legacy would be much different. He would have been the first British rider to claim the Tour, and that summer would have been Froomemania rather than Wiggo. If that were the case, we’d be crediting Froome with the explosion of British cycling, although that could be too deductive given Wiggins’ media craft and charm.

Perhaps fuelled by the injustice of 2012, Froome’s zenith was still to be reached as he got into his late 20s by the time Team Sky rolled into the 2013 season with a tried and tested formula for Grand Tour glory.

The dominant years

A.S.O./Yuzuru Sunada

A.S.O./Yuzuru Sunada

Froome would soon leave Wiggins’ shadow in 2013. He would replicate the Romandie-Dauphiné-Tour triple that year, cementing himself at the helm of the now-stratospheric juggernauts inside the ill-nicknamed Deathstar Team Sky bus.

What would follow in the years after would be complete dominance, as Team Sky shifted their focus toward their new star. After an abandonment on the wet cobbles in 2014, Froome would evolve into the sport’s most unwavering Grand Tour champion. Between 2013 and 2018, he wouldn’t finish a Grand Tour off the podium. More concretely, this would result in six Grand Tour wins during the 2010s – plus the 2011 Vuelta that was awarded retrospectively – and five WorldTour stage race victories to boot.

The manner of his wins was, for the most part, dominant. Froome benefitted from a perfect mix of climbing prowess, ruthless team support and time-trial pedigree. His dangly stick insect-like style would characterise the Tour during the 2010s, with the support of ally Richie Porte proving near unbeatable. For a long while, the Tour was a foregone conclusion once Froome decimated the field at the first opportunity in the mountains. His team would sterilise affairs thereafter, and his TT strength would see him sail away into the yellow jersey quicker than you can say Nairobi.

At times, he was criticised for being formulaic, robotic and stale. His profile had little impact among fans. If anything, it detracted them, now confirmed during the era of an equally dominant Tadej Pogačar. To this day, plenty still describe the Froome period as the sport’s most boring.

On the other hand, there were some glimpses of the human underneath the encoded skin of the four-time Tour champion. His daredevil descent off the Peyresourde, his cleated run up Mont Ventoux or his Colle delle Finestre heroics at the 2018 Giro outlive all the moments of cold-blooded dominance during the decade.

The TUE drama

A.S.O/Thomas Maheux

A.S.O/Thomas Maheux

In 2017, The Guardian unearthed a failed drug test from the 2017 Vuelta a España, with two times the legal amount of asthma medication salbutamol in his sample. Froome denied any wrongdoing, citing a TUE (therapeutic usage exception). This exception allowed him to use what would otherwise be a banned substance treat his asthma (for which salbutamol is a standard medication), which he said had intensified during the race. Later interviews revealed that he had previously refused the medication at the 2015 Tour de France, where he said a chest infection plagued his condition.

Froome had applied for a TUE from 2013 onward. Wiggins was also handed a TUE between 2011 and 2013 during his time at Team Sky for triamcinolone – another asthma treatment. This was all uncovered as part of a leak shared by Russian hacker group Fancy Bears in 2016, which listed both Wiggins and Froome on a WADA database alongside other sports stars such as tennis player Petra Kvitova. Froome’s spokesperson told the media that ‘the TUEs have all been managed and recorded in line with the processes put in place by the governing bodies’.

While Froome’s – and, in turn, Team Sky’s – TUE usage was well-documented, this attracted some sour flashbacks for some fans. Some accused the team of blurring the lines of sporting legality after Froome’s failed sample in 2017. That said, he was acquitted by the World Anti-Doping Agency in June 2018, with the board admitting that ‘the specific details of the Froome case are unique, but the result the UCI arrived at was not unusual’.

Yet, the fallout of this scandal would plague Froome and the UCI’s reputation until the early 2020s, when UCI president David Lappartient rued the legal dispute between cycling’s body and WADA on the issue. Regardless, it would still leave something of a stain on the Brit’s legacy – and one that has re-entered the spotlight following remarks made by Bradley Wiggins during the press tour for his 2025 book The Chain.

The end of the Team Sky age

ARN/Aurélien Vialatte

ARN/Aurélien Vialatte

Not long after Froome was cleared by WADA, he was dethroned at the 2018 Tour de France by Geraint Thomas. Now with the Welshman and rising star Egan Bernal among their ranks, Team Sky had diversified their leadership options. In fact, Froome would never really lead a Grand Tour roster thereafter.

A near-career-ending crash in 2019 would rule him out for the remainder of that season, which saw Sky change to Ineos. The prolonged recovery period would also see him lose out on Tour leadership duties after the pandemic, this time in favour of 2019 winner Bernal.

While he seemed to have morphed into something of a road captain – and patron wannabe at the 2020 Vuelta a España – Froome would be bought out of Ineos by WorldTour newcomers Israel-Premier Tech in something of a friendly reunion between himself and team owner Sylvan Adams, who helped to bring Froome to the 2018 Giro, which began in Israel.

This, however, felt like more than just a change of jersey. This really felt like the end of the Froome epoch. His spark was gone, as was the team he stewarded through the past decade. From this point, he had been sidelined as the sport transitioned towards new names like Bernal, Pogačar and Roglič. Now he felt like more of a white elephant than a stage race titan.

The Israel years

Dario Belingheri/Getty Images

Dario Belingheri/Getty Images

While many saw Froome’s departure as a marker of change within Ineos, the beginning of his time with Israel-Premier Tech was met with online criticism as sleuths uncovered that his social media profiles were wiped of images containing Palestinian flags ahead of his transfer in 2021.

While this marred some of the build-up to this high-profile transfer, Froome’s first handful of races in Israeli blue and white were met with little success results-wise. This theme would bleed through the remainder of his time in the squad, which seemingly culminated in a third place from the breakaway leftovers on Alpe d’Huez at the 2022 Tour de France. It was hardly the return to form he kept promising during his time at Israel-Premier Tech.

That 2022 Tour, however, would be his last Grand Tour as a professional – at least if we assume he retires in the coming weeks. The following years would be spent on the sidelines. He’d be wheeled out to press events, post-Tour crits and dressed in all-white for the ‘Ride for Peace’ in 2024. Ironic, somewhat, given his wife Michelle sparked outrage on Twitter for a slew of Islamophobic posts shared (and subsequently deleted) in the spring of 2024.

Whether 2025 was planned to be his final season or not, Froome would compete in just a couple of stage races before curtailing his season in August at the Tour de Pologne. Since then, he’s been blighted with an injury picked up in a serious accident in training in southern France. That, however, seems to be the final chapter in what had been a disappointing and downright confusing stint at Israel-Premier Tech.

What’s next?

Froome has now been pushed out of Israel-Premier Tech and is looking down the barrel of retirement. At 40 years old, it’s unlikely anyone will be willing to roll the dice on him any time soon.

Acknowledging his prestige and brand value, a future contract would come at a high cost for whoever fronts the bill. With bike brand Factor now separated from the WorldTour and former backer Sylvan Adams left without a squad to manage in 2026, Froome’s lifelines are few and far between. It’s unlikely to be a British or African team to sign him either. At this point, there are no leads on a potential contract for Froome in 2026.

It’s hardly the hero’s send-off handed to fellow Brits Mark Cavendish or Geraint Thomas – even former rival Bradley Wiggins, who bagged one final Olympic gold medal before calling it a day. All three have released new books, but a publishing deal might not be enough reconciliation for the Brit, who looks to have retired without much fuss from the British press.

So, what’s his legacy?

A.S.O./Pauline Ballet

A.S.O./Pauline Ballet

Chris Froome felt like something of a placeholder in the sport. He missed out on becoming the first Brit to win yellow, only to be overshadowed domestically by Thomas and Wiggins, despite Froome’s bigger palmarès. Likewise, on a sporting front, no matter how imperious he was, he’d later be forgotten about once Pogačar trumped Froome’s Tour achievements just less than a decade later.

However, the biggest takeaway from Chris Froome’s time will be the tactics: the suffocating Sky train of the 2010s. Froome was at the forefront of Sky’s tactical takeover, where setting high paces and following wattage on mountains yielded great Grand Tour reward. It wasn’t popular at the time, leading to Froome’s disgruntled reception in France, but it was certainly successful, leading to an almost history-equalling four Tour de France titles.

To his credit, Froome was the most reliable weapon in Sky’s arsenal throughout the decade. However, this period was one of profound changeover – yet another placeholder for something better. History goes to show that Froome’s climbing efforts weren’t quite on par with the preceeding doping era or the future galacticos of Tadej Pogačar and Jonas Vingegaard, who’d smash all of Froome’s PBs through the Alps and Pyrenees.

Unequivocally, Froome laid the groundwork for the Slovenian’s takeover. The data-driven mentality of Sky was quickly adopted – and bettered – by UAE Team Emirates and Visma-Lease a Bike. This was evident as soon as the Covid break ravaged the peloton, when Roglič’s Visma followed the same playbook to dominate stage races in 2020 and 2021.

However, a prolonged exit has left Froome dangling unfavourably by a thread of his former greatness. He was a star who didn’t know when to stop, to pack it in at his prime. Instead, he morphed into a novelty act within Israel-Premier Tech’s stable. Sadly, this somewhat overshadows the seven Grand Tour titles and countless Tour stage victories. His cleated paces up Mont Ventoux look far in the rearview mirror once we caught glimpses of him clinging onto the peloton in minor races in the 2020s.

The blueprint has been handed over to UAE Team Emirates now. Froome’s legacy won’t be known by name, but rather by practice. Unfortunately, the lack of fanfare only underlines that. Perhaps a role as a directeur sportif is to follow. But for now his star power has dried up, which is somewhat unfair given just how illustrious his time at the top was.