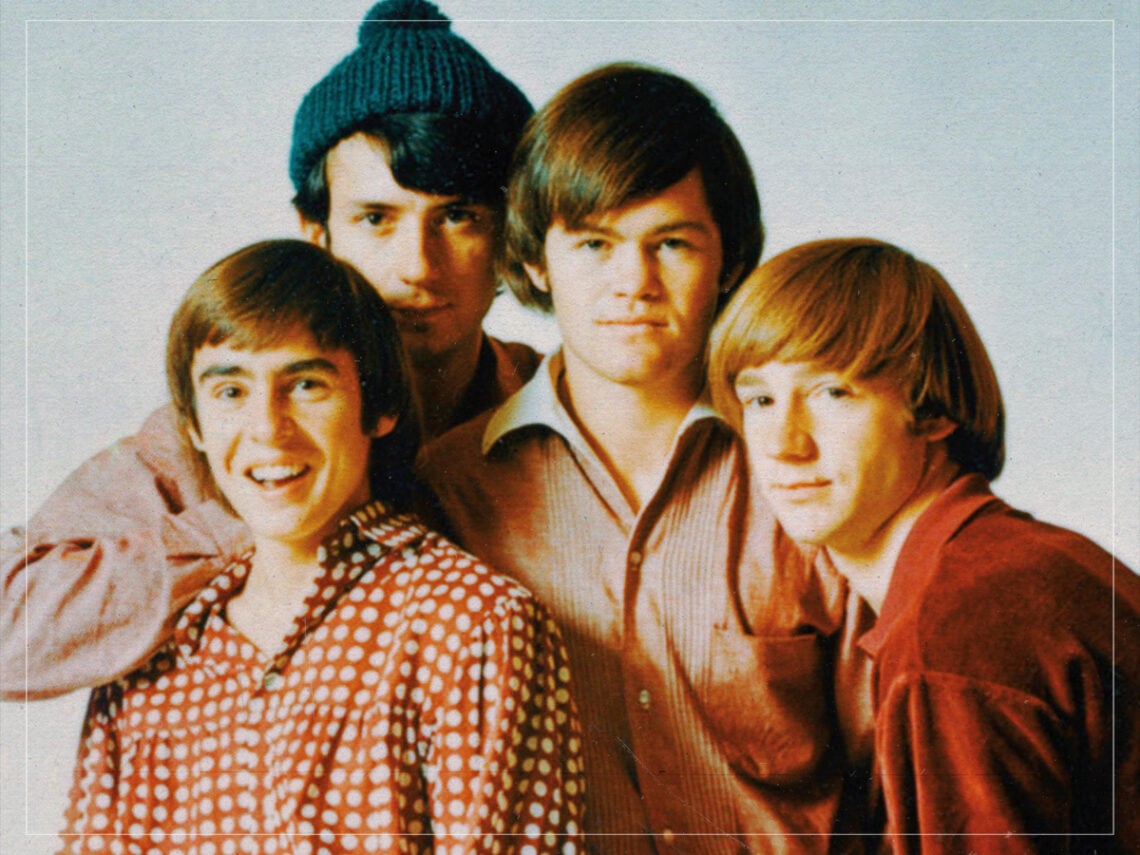

(Credits: Far Out / The Monkees)

Fri 28 November 2025 18:51, UK

Rock ‘n’ roll had barely begun in earnest before 1956. Blues, folk and the so-called ‘lowly’ pop art forms had been consigned to bars, juke joints and other working-class gatherings. But then came Elvis Presley, the advent of vinyl and radio, and within a decade, we were arriving at The Monkees when bigwigs figured that there was a buck to be made in this new boom.

In many ways, they are considered the ultimate ‘manufactured’ band. The pre-Fab Four were famously cobbled together by the producer Bert Schneider and filmmaker Bob Radelson. It’s a sign of how evident the changing times were that Radelson had actually had the idea for a show about a band in 1962, prior to The Beatles touching down in the States a few months after the assassination of JFK in February 1964 and all the ensuing mayhem. However, his pitch was initially rejected. It was too far ahead of its time – about 16 months ahead, to be exact.

But once Beatlemania had blossomed roughly a year and a half on from his rebutted pitch, it was clear to everyone that this whole rock ‘n’ roll malarkey was set to make an indelible mark on the mainstream, and TV might as well get in on the act by presenting a savoury brand for the masses. All the high-jinks, none of the illegal highs, so to speak.

This is where The Monkees came in. But a problem would soon be afoot. They began life as the first fictitious rock group, then the Pinocchio paradox had them proclaiming to producers, ‘We’re a real band!’ It says a lot about how serious the revolution became that soon, The Monkees weren’t happy just cashing cheques and wanted to prove themselves as artists.

After all, they were artists in the first place. And as later anthems like ‘As We Go Along’ would prove, simply because you auditioned for your place in pop culture doesn’t strip that away. This is a point that seems to have been missed in the unfolding story of the band. Yes, they were assembled, but the producers didn’t just put together any Tom, Dick or Harry.

The Monkees. (Credits: Far Out / Entertainment International)

The Monkees. (Credits: Far Out / Entertainment International)

Each member cast – Micky Dolenz, Davy Jones, Michael Nesmith, and Peter Tork – had been actors and musicians in their own right before being cast. Thus, to call them a fake band is a touch of a misnomer. In truth, the process was not all that different to Bob Dylan pulling together his own rock ‘n’ roll backing band when he sensed the days of folk were dying out from a roster of his own auditionees.

I suppose the difference that Monkees’ maligners will point out is that one was done with commercial appeal in mind, and the other was done with a revolution. However, any denigration hinges on whether you think pop manufactured for the mainstream is inherently artless and without cultural merit. Ironically, in this fight, you might find an ally in The Monkees’ very own Michael Nesmith.

In a paradigm of pop culture love-hate-loop with capitalism, once The Monkees caught on, the four folks at the centre were being quashed out of the creative picture in a bid to squeeze out more cash. Nesmith felt like the whole concept was losing its artistic identity, and they were purely being hard-lined for profit by the bigwigs.

However, the show’s music supervisor, Don Kirshner, thought the boys in the band were merely meddling with a well-oiled machine. He ruled the roost with an iron fist, much to the chagrin of The Monkees. This was an impasse that quickly became problematic for both parties. Soon enough, the most commercial outfit in the history of music suddenly had the worst advertising department in the world.

Kirshner had stipulated that Nesmith, as a songwriter, was only allowed to contribute two measly tracks per album regardless of his work’s quality. He would also put out material without The Monkees’ consent, refuse to let them record, and essentially used their name to spin off what he thought might be hits with the royalties logged to his name.

Of course, this seems to mark him out as not only a villain of The Monkees but art in a wider sense. Thus, the band stood fiercely in opposition and began to use their voices to deride the well-oiled machine of which they were the unhappy central cog. However, it is not without irony that the songs that Kirshner picked for them to perform, like the Neil Diamond number ‘I’m a Believer’, were so suited to the group, they pretty much stood out as signature tunes, still standing up as perfect examples of pop over half a century later.

Nevertheless, Nesmith and his mates also thought at the time that he was precluding further perfect hits and ushering the future of pop culture closer towards the Simon Cowell-like dystopia that many now see it as. They were well aware that they were a made-for-TV band, but there was a time when they saw that as a cool concept, blurring the lines of fiction and reality in a brilliant post-modern masterstroke. Now, they were just a cash-in parody.

They decided to do everything in their power to turn that tide. But so did Kirshner. So, even if it was to his own commercial detriment, he made his rebuttal. When Kirshner snuck out More of The Monkees without the band’s approval while they were out on tour, Nesmith turned to the press and called it “the worst album in the history of the world.”

This set in motion a rather obvious war. Kirshner began trying to subtly undermine the artistry of the actual band members and made sure the press knew that they were entirely manufactured, while the band tried to push for more creative control in any way they could and lashed out at anything beyond their approval.

This might have ended in the disbandment of the band in 1970, but the self-same war seems to be routinely recapitulated in pop culture. The sorry predicament that The Monkees found themselves in at the end of the ideological 1960s is indicative of the increasing commercialisation of art.

The tale is an oddity, but it seems rather tragic – a vignette of a misstep in culture – that The Monkees are now largely seen as an entirely manufactured band whose hits go to show that even prefab pop can be catchy, as opposed to a very clever and prescient art project that proved how great songwriting performed with sincerity can have worth and be virtuous even if it’s inherently designed to be commercially concurrent in the first place.

Related Topics