It may sound a little gross, but your poop could hold the key to saving lives. While many of us have been flushing it away without a second thought, feces are now in demand in the world of medical research. Stool banks, like the ones popping up across the U.S., are collecting and processing human feces to treat severe gut diseases, and even paying donors for their trouble.

This emerging field, known as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), is gaining traction as a way to treat chronic conditions. And believe it or not, it’s not just about fighting infections. Researchers are also looking at how fecal transplants might help treat autism, obesity, some cancers, and more.

Fecal Transplants: More Than Just Poop

You might be wondering: what’s the big deal about feces, anyway? Why are doctors and researchers suddenly so obsessed with it? It turns out that your gut is home to a whole community of microbes that play a role in keeping you healthy. These microbes help with everything from digestion to immune function, and when they get out of whack, it can lead to all sorts of health problems.

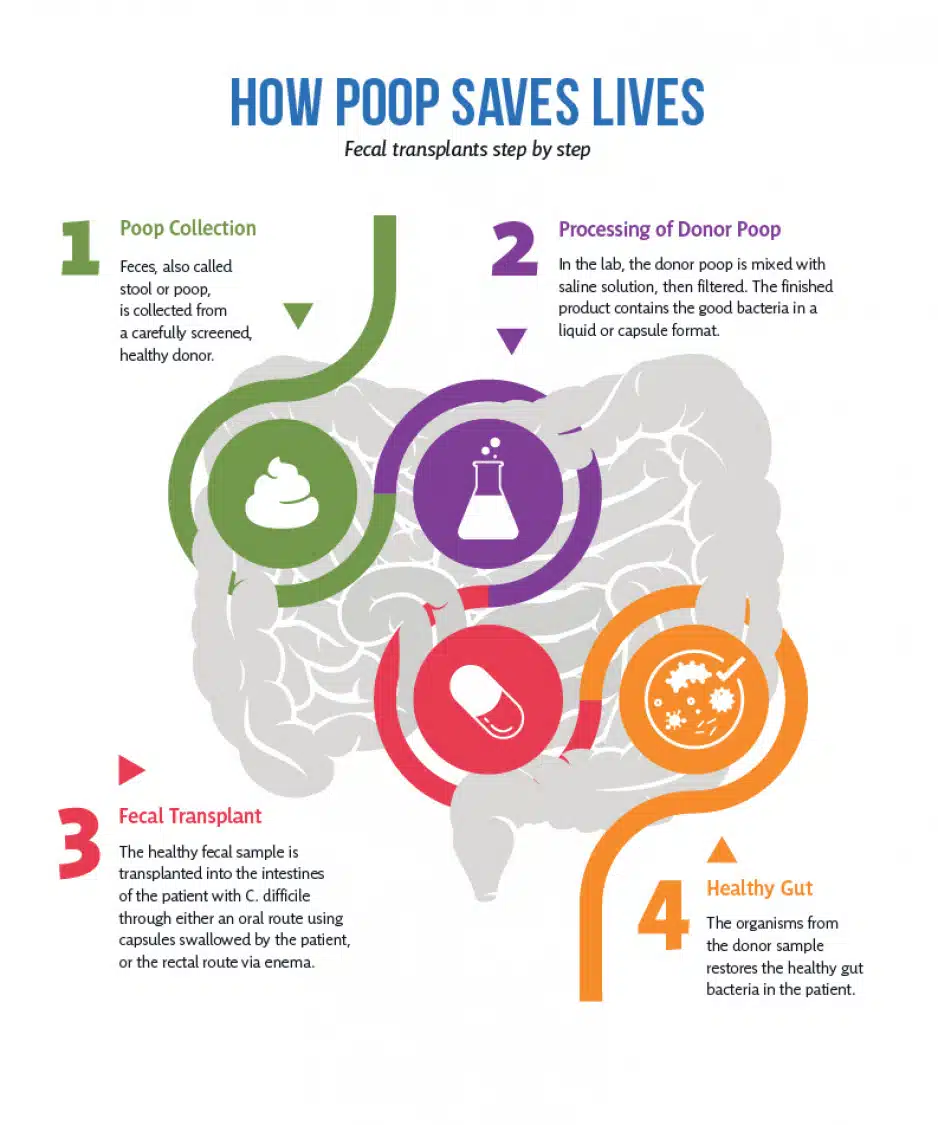

Step-by-step process of fecal transplants. Credit: St. Joseph’s Health Care London

Step-by-step process of fecal transplants. Credit: St. Joseph’s Health Care London

Based on research featured in the St. Joseph’s Health Care London, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) involves transferring healthy stool from a donor into someone with a diseased gut microbiome. The idea is to restore balance in the gut, which can help treat infections, inflammation, and other conditions. While FMT is most commonly used to treat recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections, there’s growing interest in its potential for treating a variety of other diseases.

“The idea is to use it for ‘poo’ transplants, otherwise known as fecal microbiota transplantation,” explains Associate Professor Nadeem O. Kaakoush from UNSW Sydney. “That’s when poo products made from healthy donor poo are transplanted into another person to improve their health.”

Not All Poop is Created Equal

Of course, not everyone’s stool is up to the task. As much as researchers might like to use any available poop, there are some strict requirements for donors. They have to be healthy and free of all kinds of nasties—viruses, parasites, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and so on. And even if someone looks perfectly healthy, their stool might not be good enough to use for medical treatments. Dr. Kaakoush also explained that the process of selecting donors is rigorous.

“When we transplant poo, we want to make sure the donor is free from blood-borne viruses (such as HIV or hepatitis). We also want to make sure their poo is free from parasites, and disease-causing viruses and bacteria (such as Clostridioides difficile) and certain antibiotic-resistant bacteria.”

On top of that, donors must live close to a stool bank, as fresh samples are crucial for transplant success. Even with all these hoops to jump through, there’s still high demand for quality stool.

💰 Did you know you can get paid for donating poop? Some groups pay for healthy stool samples to use in research and medical treatments! 💩 GetPaidToPoop pic.twitter.com/BoZFfmX1A6

— Dr. CZ (@AngelMD1103) July 29, 2025

Donating Poop Could Pay Off

As demand for fecal donations rises, stool banks are offering compensation for qualified donors. Some programs, like GoodNature, offer up to $1,500 a month for regular stool donations.

While that might seem like a strange way to earn a paycheck, it’s becoming more common as the medical field recognizes the importance of these donations. As Dr. Kaakoush puts it:

“It is likely your donation will treat someone with recurrent C. difficile infection. Otherwise, it would be used in a clinical trial or study to treat another important medical condition.”

The FDA has already approved two commercial FMT products—Rebyota and Vowst—both designed to reduce recurrence of C. difficile infections. The success rates for these treatments are impressive, with Rebyota showing a 70.6% success rate compared to 57.5% with a placebo. Meanwhile, Vowst helped reduce recurrence in high-risk patients to just 12.4%.

“We’re a long way from replicating the entire gut microbial community in the lab. So we have to rely on live microbial products made from donated poo as research moves from the laboratory bench to the clinic,” he concluded.