The hunt for the holy grail of a longer life has consumed the careers of the brightest scientists and dented the fortunes of some of the richest entrepreneurs. Now the quest has reached a laboratory outside Cambridge, where the work of two young, brilliant sisters has attracted the attention — and financial and expert backing — of billionaire investors, research philanthropists, the UK government, leading scientists and Nasa.

Carina Kern, 31, and Serena Kern-Libera, 37, are self-confessed workaholics, who sometimes finish each other’s sentences and together bring a boffin’s vision and a corporate lawyer’s knowhow to the race to extend human life.

Kern, who is the scientific brain of their operation, wears her nerdiness lightly and has the vital startup skill of being able to communicate what she is doing in an engaging manner that anyone can understand. “I’m very ambitious,” she says with matter-of-fact bluntness. “And I’d like to get the first drug approved for ageing.”

• 15 easy ways to live longer (and four things you should stop now)

Two years ago the sisters started LinkGevity, with Kern-Libera — a lawyer who has worked at a “magic circle” firm, the Bank of England and the Treasury — heading the operational and legal side of things, while Kern, an expert on longevity, takes the lead on science.

As positive data has emerged from Kern’s work in the lab, investors, including Michael Hintze, the Australian-born billionaire fund manager, have signed on. The Francis Crick Institute made an equity investment. The government’s innovation agency, Innovate UK, and the European Union have provided grants. Nasa chose LinkGevity as one of a dozen global innovations (and the only UK one) for its space health programme.

LinkGevity is a bijou outfit of just six full-time staff, including the sisters. But they include Bill Davis, their head of research and development, who is a former director of scientific operations at pharmaceuticals giant GlaxoSmithKline, and their AI work is led by Nikodem Grzesiak, who was previously at Cern in Geneva.

Jeff Bezos, an investor in biotech company Altos Labs, and, right, Peter Thiel, a supporter of the Methuselah Foundation

GETTY IMAGES, SHUTTERSTOCK

Kern approached some important figures in fields central to her work to explain what she believed was an important potential breakthrough. These included Joseph Bonventre, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a world expert on kidney disease, and Professor Justin Stebbing, the renowned oncologist and expert on cell death. “They were sceptical at first, as this was a huge claim we were making,” she says. “But as any good scientist, you ultimately follow the data and that’s what I think won them over.” They gave her more than their blessing; they joined LinkGevity’s advisory board.

The search for a breakthrough that will enable humans to live, if not for ever, then at least for another decade or decades, has devoured huge chunks of some of the largest fortunes amassed. Jeff Bezos and Yuri Milner, a Russian-born internet mogul, are financial backers of Altos Labs, a biotech company based in California and Cambridge that is focused on cell rejuvenation and boasts a team sheet full of Nobel laureates. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, is behind Retro Biosciences, which is committed to adding ten healthy years to the human lifespan. Peter Thiel, the cofounder of PayPal and Palantir, has poured a chunk of his wealth into the Methuselah Foundation. Its mission statement? “Making 90 the new 50 by 2030.”

Both gene editing and cellular reprogramming show promise. Drugs, including rapamycin, have been found to extend the lives of mice, as have senolytic drugs, which selectively remove senescent or “zombie” cells. There is excitement about the potential for metformin, a diabetes drug, to delay age-related diseases.

• Read more expert advice on healthy living, fitness and wellbeing

And research is focusing on whether glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) drugs, such as Ozempic, originally developed to treat type 2 diabetes and now hailed as weight loss wonder drugs, could have other life-extending powers, including to fight heart and neurodegenerative diseases.

At LinkGevity, the sisters are exploring a different approach. One of the problems with tackling ageing, Kern says, is that tangible degenerative change, whether it is in the form of cardiovascular or kidney disease, muscle loss, Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, will have a multitude of underlying causes and changes arise simultaneously, leading to multimorbidity. She decided to identify the key “nodes” in our biology that give rise to the greatest level of destructive change. Using what she calls her “blueprint theory”, enabled by AI, she zeroed in on one node: necrosis, or undesirable and unregulated cell death. “That pinpointed necrosis as a key node giving rise to the greatest level of change,” she says.

Sam Altman, backer of Retro Biosciences, and, right, Yuri Milner, who has invested in Altos Labs

GETTY IMAGES

As cell membranes lose their integrity, they become flooded with calcium, which destroys the cells from the inside. Stopping this from happening offers enormous potential for prevention of disease in multiple organs. “The unfortunate consequence of modern medicine is you take a drug for one problem and you don’t know if it’s having a negative effect on another. So can you move beyond that to the systems-level approach of treatment?”

Testing on mice has shown highly promising results

Her modelling found that cells could be protected if two specific channels through which the calcium was entering the cell could be blocked. New formulations of existing drugs were tested on human cells in their lab at Babraham Research Campus, an ecosystem of commercial bioscience companies in parkland south of Cambridge, where we are talking today. The results were promising, so LinkGevity asked an independent research organisation to replicate the experiments. “I think they thought we were a bit mad to begin with,” Kern says. “They said, ‘We’re happy to take your money but you realise this is most likely not going to work?’ And then they called me and said, ‘It’s worked! We can’t believe it.’ ”

Testing on mice is close to completion and has also shown highly promising results, the sisters say. The plan is to initiate human clinical trials in the next few months.

The world of longevity science is littered with disappointed researchers who saw thrilling results in rodents that did not translate to humans. Is there any reason to believe LinkGevity’s anti-necrotic will fair any differently?

The sisters are cautiously optimistic because necrosis is a fundamental and universal biological process across the animal kingdom. Most processes targeted by other longevity interventions are gene-controlled and gene variations across species often cause animal results to fail in humans. Necrosis is not gene-controlled and so avoids this problem.

The first human trials are planned on the kidney

The data, Kern says, shows that the drug can block necrosis across species, including in complex human tissues, and is not expected to cause trade-offs, such as the cancer risks that have ended other promising drug programmes.

The first human trials are planned on the kidney. “The kidney is one of the most susceptible organs to stress, so it’s often the first to fail,” Kern says. “Hence kidney disease is the ninth leading cause of death globally.” As necrosis is universal to all organs and tissues, it is hoped that if the drug is successful in blocking necrosis and associated tissue degeneration in the kidney, it will also work in other organs.

The plan is to test it on people prone to kidney disease to see if those who are given the drug show signs of prevention of kidney degeneration and ageing.

This is what made Nasa take notice. Rapid tissue degeneration and ageing, particularly of the kidneys, is a key issue that will need to be addressed if humans are to venture on long journeys into space. Nasa has provided mentoring, advice and AI tools to help with the anti-necrotic project.

The sisters’ journey into the competitive world of longevity science began a long way from Cambridge. They grew up in India. Kern was seven years old when she first started asking the big questions that would set her on a personal quest.

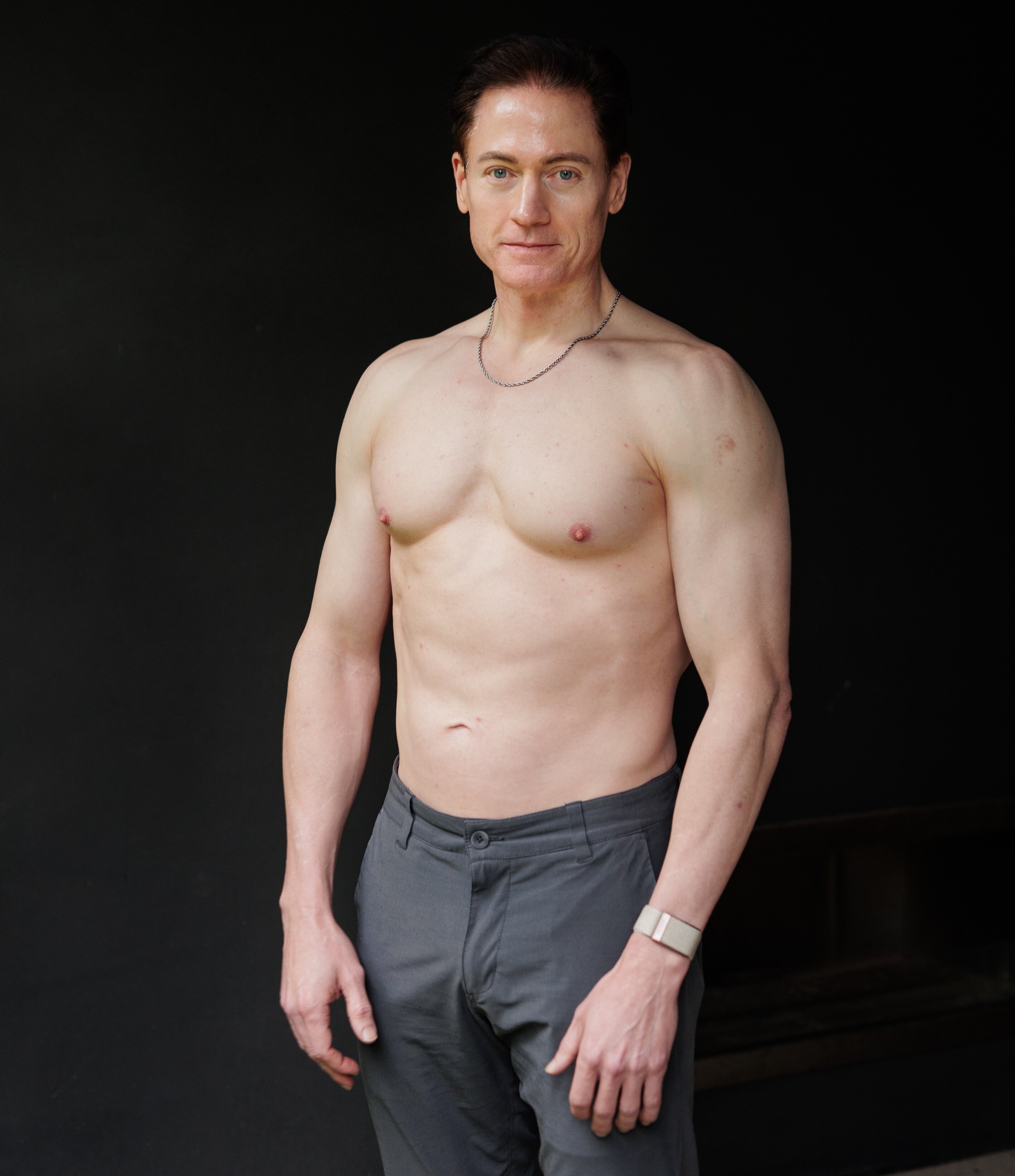

Bryan Johnson, 48, tech entrepreneur and biohacker, about whom Kern says: “A sample size of one does not a clinical trial make”

AGATON STROM/REDUX/EYEVINE

When her grandmother became ill, she assumed she would be patched up swiftly and sent home. “Not only did she not come home but, my goodness, it was the worst downward spiral. I remember my father taking me into the ICU and he said, ‘You may have to say goodbye.’ I just couldn’t understand why the doctors wouldn’t do anything. All I would get from them was, ‘She’s old and this is normal and natural.’

“At a very early age I said, ‘Fine, I’m going to go into ageing.’ This was one thing I could never let go of. In a way this is a calling for me. I typically work 24/7 and I don’t take weekends off. But I enjoy it.”

Not trying to make us immortal

This all sounds tremendously serious, but she and Kern-Libera, who live close to each other in London, also laugh a lot and tease each other.

The sisters are not trying to make us immortal. “I think Serena and I share this view, which is that neither of us is scared of death,” Kern says. “But we are both scared — and I’ve seen this with my grandmother — of going into this decrepit state where you lose your human dignity. The ambition is to try to intervene in this loss of human dignity, this degenerative debilitating state that individuals go into.”

Kern-Libera is pregnant and I mention that I once interviewed a Harvard professor who claimed that in the future it would not be outlandish to live to 150. Does Kern have any confidence that her soon-to-be-born nephew will enjoy such longevity? “I’m not going to put a specific number on it because I can’t,” she says. “But what I can say is, if you take out the things that are shortening your life and you take out the debilitating diseases that are affecting the quality of your life, the debilitating conditions and non-life limiting pathologies that are reducing your quality of life, of course you will live longer and healthier.”

Longevity science has undoubtedly attracted some eccentric figures.

“It depends which eccentrics we’re talking about,” Kern says. They don’t want to mention names. I raise the freakish spectre of Bryan Johnson, the American tech entrepreneur and the world’s most prominent biohacker, who spends $2 million a year trying to live up to his motto: “Don’t die”. This involves rigorous exercise, a minutely calibrated diet, more than 50 pills a day, the occasional blood transfusion from his son and the exhaustive monitoring of his body, down to the duration of his night-time erections. “The most diplomatic thing I can say there,” Kern says, “is a sample size of one does not a clinical trial make.”

Elsewhere in our conversation she says that “snake oil” is being promoted by some in the longevity science sphere. “There’s no other word for it.”

“If you take out the debilitating conditions that are reducing your quality of life,” Kern says, “of course you will live longer and healthier”

TOM JACKSON FOR THE TIMES MAGAZINE. HAIR AND MAKE-UP: CHRISTINA LOMAS AT DAVID ARTISTS USING KERASILK AND LISA ELDRIDGE

She adds a word of caution about the babble of optimistic chatter around Ozempic and the other GLP-1s and longevity. “The thing about GLP-1s is we don’t know all the mechanisms around them. As a consequence, one day in the news you’re hearing it’s going to work against neurodegeneration and cardiovascular disease, the next day you’re hearing it’s causing pancreatitis, muscle loss, sarcopenia, bone density loss, macular degeneration and so on.”

The sisters are half-Indian, half-Swiss. Their grandfather, who was Swiss, went to India to set up a company that supplied gemstones for Swiss watches. He and his Swiss wife settled in the Nilgiri Mountains of Tamil Nadu in southern India. Their father started as a deck boy, served in the Swiss merchant navy and now is a captain on oil and gas exploration ships. Their Indian mother is an abstract and landscape artist.

Serena scored the highest GCSE results in India

As girls they attended the same Catholic convent school their father had been to, with 60 pupils in a class. “My parents were really keen that we just attended the local school,” Kern-Libera says. “They didn’t want us to have any kind of elitist upbringing. It was a good school, but it was no frills. They wanted to make sure we appreciated that there is value in hard work. What was really ingrained in both of us was wanting to make a positive contribution to society.”

Kern pipes up that when her sister moved on to an international school she scored the highest GCSE results in India. She studied law at the London School of Economics and was a trainee at Slaughter and May, the “magic circle” law firm. She met her husband at law school. After a few years as a corporate lawyer she moved to the Bank of England where she headed a team working on post-Brexit trade strategy and was seconded to the Treasury.

• I’m 45. Will $2 million a year help me turn back the clock to 18?

At school, Kern was a rebel. “Mum would frequently be called to the principal’s office and with Serena, it was always when she was winning an award. With me, it was when I had got into some type of mischief.”

‘I was told it was career suicide’

She studied for an undergraduate degree and then a PhD at University College London, where she was a research fellow at the Institute of Healthy Ageing. In the Eighties it was found that if certain genes were switched off in Caenorhabditis elegans, a type of nematode worm, lifespan could be extended. C. elegans became the focus of countless studies. But there was a “large translation gap to humans”, which Kern explained in her doctorate. “When I first presented it, I was told it was career suicide: ‘Who are you to question whether or not the animal that these vast numbers of labs around the world are using is perhaps not the best animal to be studying ageing in?’ ”

There will be other sceptics on the long road ahead through trials and possible drug development (which they hope will take a few years, rather than decades). Those sceptics will question their science, of course. Some may even question their motives. After all, there are many people hoping to build fortunes out of the human desire for longer life. But I don’t see dollar signs in their eyes when they show me charts of positive data on their laptops. When I ask if they hope that this will end with a drug giant buying them up and turning them into billionaires, Kern-Libera is mildly reproving. “I don’t think we went into this because we want to be billionaires,” she says. Her sister adds, “All of us are in this because we want to do something good, at the end of the day.”

And unlike some others in their field, they are not making dramatic claims that many of us will be living the good life as sprightly supercentenarians in the 22nd century. Even if their dreams of an anti-necrotic drug are realised and we can keep the ageing process at bay, there will always be pathogens waiting to take a pop at us. “It is not going to stop everything,” Kern says. And then she adds, with brutal frankness and a mirthful chuckle, “There are plenty of other things that can kill us.”