In East Africa’s desolate Afar region, where temperatures routinely reach 130°F, the Earth is opening up. Massive cracks have begun cutting across the landscape, pulling roads and farmland apart, marking what scientists say is a rare, live glimpse of a continent in the process of breaking itself in two.

The ground beneath Ethiopia, Kenya, and parts of Tanzania is shifting. Slowly, but unmistakably. Tectonic plates that make up the continent’s crust are inching away from one another—so gradually that the changes often go unnoticed, but sometimes abruptly enough to reshape the land within days.

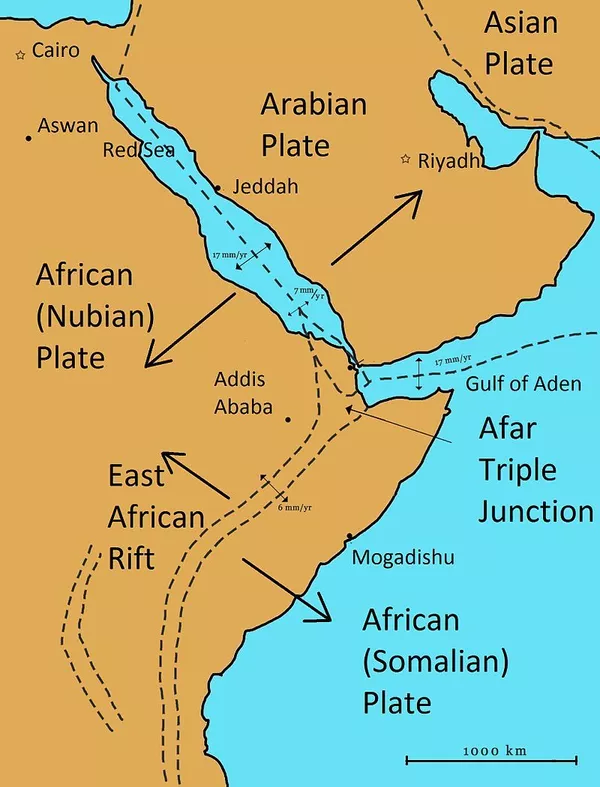

At the heart of this transformation is the East African Rift System, a massive scar stretching more than 3,000 kilometers from the Red Sea to Mozambique. While this rift has long been seen as a case study in geological patience, new data suggests the pace and intensity of its evolution may be faster than previously understood.

A Tectonic Rift in Real Time

The East African Rift is one of the few places on Earth where scientists can observe the transition from a continental rift to an oceanic rift. At the junction of the Nubian, Somali, and Arabian tectonic plates, the rift is actively pulling the continent apart, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In 2005, a dramatic 35-mile-long crack appeared in the Ethiopian desert, a rupture scientists confirmed was caused by tectonic movement. The event was so abrupt that it replicated several centuries of plate drift in less than two weeks

“This is the only place on Earth where you can study how continental rift becomes an oceanic rift,” said Christopher Moore, a doctoral researcher at the University of Leeds, who has used satellite radar to track rifting activity in the region.

Scientists are now detecting oceanic crust forming beneath parts of the rift, signaling a deeper shift from land to seafloor. That crust, denser and chemically distinct from continental rock, is typically found only under existing oceans—a clear sign the Earth’s architecture is changing from within.

Magma, Fractures, and the Pressure Below

The split isn’t just surface-level. Deep below, magma is rising through the mantle, pushing crustal plates apart and creating frequent earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The region’s unique geology makes it an unparalleled laboratory for studying the birth of new oceans.

Researchers suspect a plume of superheated rock is rising from Earth’s interior beneath East Africa, creating pressure that builds until the crust fractures. This theory aligns with the kind of sudden ruptures seen in 2005.

Geophysicist Cynthia Ebinger, who has conducted fieldwork across the Afar region, described it to NBC News as an environment that’s both scientifically invaluable and brutally harsh. “It has been called Dante’s inferno,” she said, referring to the sweltering heat and harsh terrain.

The rifting is not steady. Ebinger’s research has shown that periods of apparent geological calm are often followed by sudden, explosive tectonic activity, as built-up magma forces its way upward through the crust. In her analogy, it’s like an overinflated balloon that eventually bursts.

The Red Sea’s Next Move

If the rifting continues, scientists estimate that in 5 to 10 million years, the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden could pour into the rift valley, creating a new ocean. This would isolate parts of eastern Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania, forming a separate landmass akin to Madagascar.

This scenario is more than theoretical. The Arabian Plate has already been moving away from Africa for more than 30 million years, forming the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden in the process. Today, the Somali and Nubian plates are separating at rates of 0.2 to 0.5 inches per year, according to Ken Macdonald, a marine geophysicist and professor emeritus at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

“As the plates peel apart, material from deep inside Earth moves to the surface and forms oceanic crust at the ridges,” Macdonald told NBC News. “We can see that oceanic crust is starting to form.”

monitoring a moving planet

For decades, the rift was seen as slow and stable. But the advent of high-precision GPS and satellite radar is rewriting that narrative. These tools now allow researchers to detect ground movement with millimeter-scale accuracy, revealing previously undetectable shifts in Earth’s surface.

This technology is not only improving models of plate tectonics—it’s exposing just how dynamic Earth’s crust really is. As the plates continue to drift, the transformation will influence not just maps, but infrastructure, climate, and energy strategies across East Africa.

Some countries are already tapping into the region’s geothermal potential, using the same tectonic heat that drives earthquakes to generate renewable electricity. But the trade-off is risk: fragile infrastructure, seismic hazards, and displacement zones are all real consequences of a continent in transition.