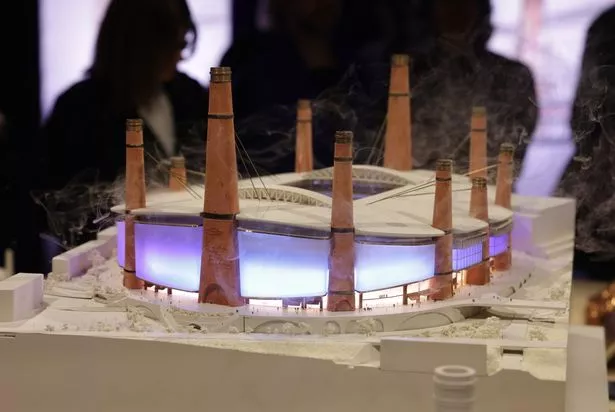

Birmingham City hope to move into their new stadium, The Powerhouse, at the Sports Quarter in 2030 The design of The Powerhouse Stadium, Birmingham City’s proposed new home

The design of The Powerhouse Stadium, Birmingham City’s proposed new home

Little over a week since The Powerhouse was unveiled to the world, Birmingham City’s proposed new home is still in the minds of everyone in the Second City and beyond.

An eye-catching design for a 62,000-seater stadium that includes 12 chimneys, two which stand at 120 metres tall, will be the centrepiece of the Birmingham Sports Quarter.

Knighthead have set the ambitious opening date target of 2030 to ensure Blues are playing at their new stadium at the start of the 2030/21 season.

London-based Heatherwick Studio and US firm MANICA, with some help from Steven Knight, created the already iconic design for The Powerhouse.

Eliot Postma, who is one of the lead architects for Heatherwick Studio, was a guest on the latest edition of the Keep Right On Podcast to discuss a design which has grabbed worldwide attention. Here is a transcript of the interview with him…

Q: Just give us a little bit of background about Heatherwick Studio and what projects you’ve worked on in the past.

EP: We’re a design studio based in London in King’s Cross. We’ve been going just over thirty years. We’re about 250 or 260 different designers, problem solvers. We work on mostly like large scale architectural projects, but have designed things from London’s Red Bus to the Olympic Cauldron at the 2012 Olympics, then up to really large architectural projects. I spent ten years working on Google’s headquarters, both in California, but also their headquarters here in London.

But we haven’t yet had the chance to design a stadium. We’ve done a few stadium designs that weren’t realised. And yeah, so we couldn’t be more excited to have the chance to do something that is essentially all about like bringing people together in the real world to have incredible experiences with one another.

Q: Is designing a stadium the pinnacle for architects?

EP: “What kind of excites us is trying to help change the direction of cities to make them more joyful and engaging and essentially human. And so part of that is we look for opportunities that are very public-facing that will contribute to cities and the public realm and try and be a platform for bringing people together.

Over the last decade or so, we’ve become more and more sort of separated from one another. Digital technology is a brilliant platform for that. But ultimately, we believe that the future of cities is using them as a platform for socialisation in real life. And so I guess you could say that a stadium in a way is like a temple of togetherness.

It is like the ultimate version of bringing everybody together, having a collective in real life experience, so in a lot of ways it is kind of a dream project for us.

Q: When you entered that competition was there a brief given by Knighthead of what the stadium must have?

EP: Yes, I mean, there was a brief in terms of size, so that, you know, they wanted it as sort of a 60,000 seat stadium. There was a brief in terms of values. So they were really looking for something that was going to be a landmark and a statement of intent, both for the club, but also for the future of Birmingham, Birmingham as a city. And also there was in there this duality between creating this amazing sense of pride for the Blues fans, at the same time this sense of intimidation for away fans and really trying to maximize that opportunity of home game advantage that’s so important in competitive sports.

Steven Knight (left), Tom Wagner and architect Eliot Postma (right) at the launch of Birmingham City’s new stadium, The Powerhouse

Steven Knight (left), Tom Wagner and architect Eliot Postma (right) at the launch of Birmingham City’s new stadium, The Powerhouse

Q: How long did it did it take to put your design together?

EP: “The competition was about three months which, for something of this scale, is pretty quick, but it’s relatively standard. It means that you get a good chance of really thinking about the complete vision of the building, but the design is by no means finished. There’s still a lot more, there’s a lot of evolution still to go through.

Q: Can you give us an idea of the number of people that would have been involved in putting that big project together?

EP: “So even at the competition split stage it was a huge team because us together with MANICA were thinking about the architecture. So thinking about how the building looks, feels, thinking about the bowl and how you create the most incredible fan experience you can inside the stadium. But alongside that, you’ve got engineering teams looking at structure, looking at MEP (mechanical, electrical and plumbing), looking at sustainability.

We wanted to work with people that could specialise in understanding the potential of retail and how that would help activate the stadium and the base of the stadium, not just on game days, but 365 days a year. So we had specialists looking at that, as well as working with consultants that would really help us engage with both the fan community and the local surrounding communities.

The Wheels site is at this kind of amazing crossroads of all of these different demographics and communities in Birmingham. So how we can create a place that feels welcoming to all of them, as well as that kind of central fan base is also a really important part of the project.

There’s a huge number of people involved and that will only grow now that we’re going to move into looking to deliver it.

Q: Have you worked with MANICA before?

EP: We haven’t worked with them before. We were invited into the competition and we knew that because we haven’t designed a football bowl before we knew we wanted to try and work with the best of the best in that level of expertise. And we also knew that the ambition for the stadium, Tom being from the US and he was looking at the best the NFL and the American stadiums and what they have on offer there and how could we look to bring some of that to the UK? And so MANICA have designed stadiums and bowls both in Europe for football, but also in the US for some of the most recent NFL stadiums. So they just felt like a really good fit being able to bridge that expertise.

And then, yeah, the opportunity to work with Steve (Knight), Thomas (Heatherwick) and myself were lucky enough to meet Steve a few months prior to the competition, just unrelated. We got to know him because of his work around Digbeth and in Birmingham and his film studios there. And so we had actually walked around Digbeth very close to the site a couple of times with Steve. And so then when the competition dropped, we knew that alongside MANICA, the other bit that was missing for us being based in London was you know… Steve’s a third generation Blues fan. He lives and breathes Birmingham. And we wanted someone that really understood the city, understood the cultural context, but really understood the club and the fan base. And so that was really important to us to get that in the team. And thankfully, Steve jumped at it. Frankly, he said yes pretty quick. And I think he’s now an aspiring young architect!

Q: Were chimneys always going to be part of the design?

EP: So it came about, I wouldn’t say that it was always going to be that. Obviously, it’s a very strong visual idea, which we knew that the client was looking for something like that. Like, how do you make a memorable destination that could kind of only be for Birmingham City? And for us how it came about was actually there were sort of two streams of work going on. where one, we were absolutely trying to understand the site. And when I say the site, I don’t mean Birmingham, I mean the Wheels site itself, which has this amazing history within Birmingham of being where the brickworks were. There are a whole number of brickworks on the site that were making the bricks for the canals and the viaducts and Victorian Birmingham. And so that gave us a material story that we knew we wanted for the stadium.

So many contemporary stadiums can feel a little bit anonymous and a bit generic, they can feel like spaceships that you could pick it up from one city and put it in another one and it would be fine and they’re amazing facilities but they don’t necessarily feel grounded specifically in a place. So for us, how we could make something that felt like it was literally grown out of the history of the site but still felt very contemporary was the starting point. And so the bricks gave us that kind of material grounding, that richness, that warmth, that texture that is so the Midlands, that is so Birmingham.

But at the same time, we were thinking through the structural problems of building a building of this scale, like how do you create a stadium efficiently at this scale, particularly one that’s got an operable roof, which is very ambitious. There aren’t many stadiums in the world that have delivered on that. And so often what happens is you’ll build masts, so big vertical pieces of structure, and then you hang this really heavy operable roof from those masts in sort of an efficient structural solution to that. And so these two things came together where we were thinking about this material story about the site, which had this historic silhouette of these peaks of the chimneys that were part of the brickworks on the site and at the same time needing these vertical bits of structure to hold the roof up.

And then one thing that we didn’t talk about, there was then layers to this that came about that we wanted basically to try and reinvent the stadium mast. Like what other pieces of infrastructure can we put into, how can we innovate that piece of structure? And so it became this exercise of looking at what else could go into it. And actually there’s a Birmingham-based Victorian architect called John Chamberlain who built loads of Victorian schools. And one of his innovations was he built these brick towers in the centre of the schools as part of the natural ventilation. So it would pull the warm air out of the building and it would go up these towers and get exhausted out. And actually one of the schools was on the site as well. And so then this story about well if we’re building these vertical elements – the roof is going to close, it’s going to get really hot in the stadium – can we be pulling that air out and up these vertical elements? And then it became about, well, let’s move people around in them, let’s put the cords in them, let’s have the stairs, the lifts. What can we bake into this piece of vertical structure? And then can we clad that in the materiality that’s going to ground it in the site? And so all of that complex stuff came together with this, like ultimately with this idea of can we create this like iconic landmark silhouette that will define the stadium for this place?

The design of Birmingham City’s proposed new stadium, The Powerhouse

The design of Birmingham City’s proposed new stadium, The Powerhouse

Q: Historically, chimneys haven’t been something that are particularly good for the environment and that question did come up in the press conference afterwards. So, can you tell us how this stadium is going to be environmentally friendly?

EP: Yes, it’s certainly part of the aspiration to look at how they can be part of the sustainability story. So a really big part of it is what I spoke about, about that natural ventilation and of pulling air. So typically what you would have is basically huge fans that would be driving air out of the stadium, normally just below the roof line. It wants to be at the top as high as you can do it. So it drives it out the roof line. And so this is part of the engineering that’s still ongoing, but essentially that vertical stack is called the stack effect of being able to pull air naturally out of the stadium will massively reduce the amount of energy required for fans. The hope is that we may be able to do without them altogether, or they would only need to be turned on on very focused points, maybe during a concert or whatever it might be, but that largely we can use those architectural elements to minimise that energy requirement.

And then the other big part of this from an energy story is that typically when you have a sliding roof on a stadium, so many of them are like shells, like these two rigid shells that they slide out over the rest of the roof. And so if you imagine that area that the pitch is, those pieces of roof need to slide over the rest of the roof and they cover it up. We’re creating something that’s much lighter weight, which reduces the steel work. It’s a concertina-type roof. So it sort of collapses up on itself. It doesn’t have to slide over the rest of the roof. And what that does is it frees up all of the roof because the movable bit isn’t covering parts of the roof. The whole thing can be covered with solar panels, which is a huge area. And I think we’re close to 10,000 solar panels on the roof of the stadium because we’re not using loads of the area to move the roof onto. And so that is going to power one hundred events a year just from the energy taken off the roof, which is an enormous amount of energy.

And then the other part, that brick story, that we would love to really lean into reclaimed material. And there’s a huge amount of reclaimed brick stock in the Midlands. And we would love to see if we can bring that in. We would love it if it had that richness and feeling of history in the stadium and whether even we can take bits from St Andrew’s. Like, can we take the fan bricks that are there and place them in the chimneys so that fan legacy continues. And of course, there’ll be hopefully new fans that want fan bricks and to have their name at the base of the chimneys. And so, yeah, we’re excited about the opportunities there as well. So there’s a number of different kinds of strategies that are coming together to really try to push the sustainable credentials, because ultimately it is a really large undertaking. It’s a really big building so we are trying to do as much as we can.

Q: Talk to us about the elevator experience in one of the chimneys…

EP: So often stadiums, when they hit the ground, offer very, very little outside of match day. There’s this amazing hub of activity during match day, but then the rest of the time, they really don’t offer much to the community. They’re actually just kind of in the way. So part of this has been about what experiences can we bring to the stadium that will bring people there every day of the week and these chimneys aren’t just about the silhouette, they’re doing these other things but part of what they’re doing is the overall experience of the stadium so I’ll come to the lift in a minute but it’s also about how they hit the ground. They’re part of the experience of bringing that materiality to where it really counts, where people are experiencing the stadium every day, where they can touch it. They frame these amazing entrance moments. And when there isn’t a match on, some of the chimneys will be open to the public so that you can walk in and kind of experience the base of the stadium. And there might be a little market hall space behind the northern chimney that’s open every day of the year.

And then on the southern chimney, The thinking is at the moment, absolutely, is there the potential of having like an immersive experience there that can be something that would be ticketed so that it can help drive revenue for the city and for the club and for the stadium, but will be a lift experience that takes you to the top of that chimney. And the lift is big enough that there could be a small hospitality offer, like a little bar up there. So you could go up there and have a drink at sunset with amazing views back to the city. But as you’re going up the chimney – it could be quite a slow journey – that the lift itself is kind of an immersive projected experience. We were excited by the idea that it’s almost like a timeline of Birmingham. So it’s as if you’re looking out of the lift, even though you’re in a brick shaft, and it starts showing you Birmingham’s evolution. As you look around, you’re seeing how Birmingham developed, as well as starting to learn about the club and the history of the club being one of the oldest clubs in English football. And then you pop out of the lift, and the projections fall away, but they match with what you then see outside. And so we just thought there’s lots of different things we could do.

You could imagine brands could take over. I know Nike are one of the sponsors, Delta are one of the sponsors, they could take over that lift experience. It could be a branded thing. Likewise, projections on the outside of these chimneys. Yeah, there’s just lots of opportunity of creating a bit of a spectacle, something that people want to come and enjoy.

A view of what the inside of The Powerhouse’s chimneys could look like

A view of what the inside of The Powerhouse’s chimneys could look like

Q: When you describe this it sounds like you’ve been there and you’ve lived it.

EP: For sure, we’re able to give a better sense digitally of what it might feel like than we were able to show at the launch event, for example. We can test our designs in VR, in virtual reality goggles where quite early on in the design process we’re able to walk around and get a sense of scale and make sure that the heights and the distances between things and the overall space feels right and that’s even before it’s necessarily got kind of materiality and things. We haven’t created that whole projection experience but in terms of getting a sense of how steep the stands feel and how do those entrances feel? Are they big enough, the arches? Does it feel welcoming? Does it feel intimidating for away fans? We’re able to get a sense of that.

Q: How will the pitch be protected when it’s removed for concerts etc?

EP: It’s similar to what’s happening at Tottenham. So Tottenham have a similar situation where they’ve got a retractable pitch. So ours will, we’ve basically got a space underneath the east stand. So there are certain points of structure that hold the east stand that can temporarily flip up to allow the pitch to slide underneath the east stand. And then there’s basically a big zone of structure, like a big truss that you can walk around it and in between the truss where the pitch would sit and be able to be maintained. It would have grow lights and it would be kind of kept in a pristine condition with enough space to have groundsmen essentially under there monitoring it in its pieces. So I think it’s currently being planned to be split into five pieces and then it’s able to then slide back into place after the NFL game or the boxing match or whatever. It’s a really important part of the stadium genuinely being flexible, to be able to host these other things, to be able to have Coldplay go there or Oasis next time they tour… It’s a really important part of being able to do that.

Q: How long will the stadium take to build?

EP: Look, they’re big buildings that can take time. I don’t want to promise a date. Tom (Wagner) is amazingly ambitious and he just wants this yesterday. And we love that because we just want things built. But, you know, you could imagine it’s easily a two year, two and a half year build. I guess the thing to hold is that there is the ambition within the club and within Knighthead to make sure this is done as quickly as possible. And for us, part of the engineering and working with the engineers has been about how we can accelerate that time that it takes to build something. It’s called prefabrication: how much can you build not on the site? So how much of the stadium can be built in really big bits offsite so that it can then be brought to site and just lifted into place? The whole design of the structure inside has been thought of in that way. We call it a kit of parts. What are the fewest number of parts that you can make the whole stadium out of to be able to deliver on that vision of getting this ready as early as possible, so it’s absolutely front of mind but I don’t want to promise any dates.

Get the latest Blues headlines sent straight to your phone

BirminghamLive has its very own Birmingham City WhatsApp community to deliver the latest headlines straight to your phone. Just click this link to receive daily Blues content and breaking news. We also treat our community members to special offers, promotions, and adverts from us and our partners. If you don’t like our community, you can check out any time you like. Click on the name at the top of your screen while in WhatsApp and click ‘Exit Group’. Read our Privacy Notice.