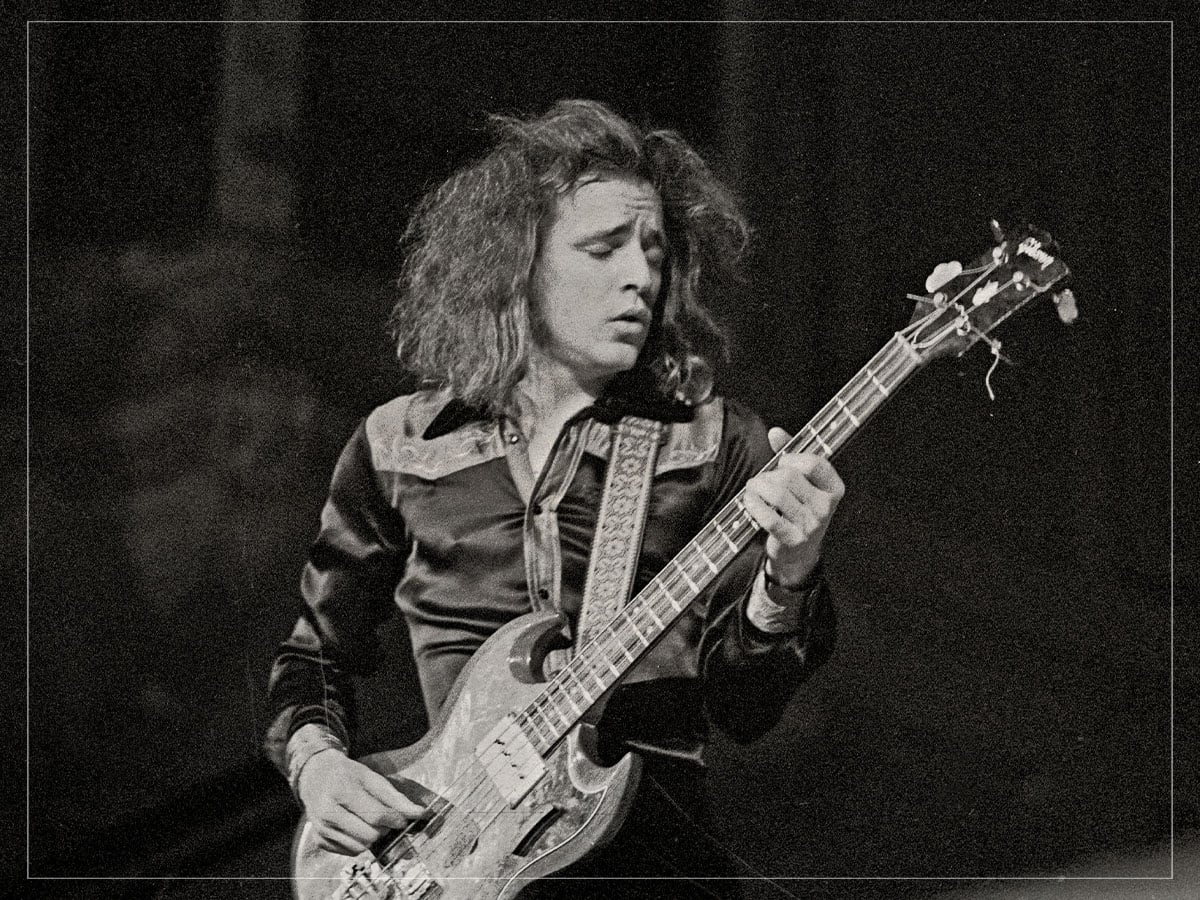

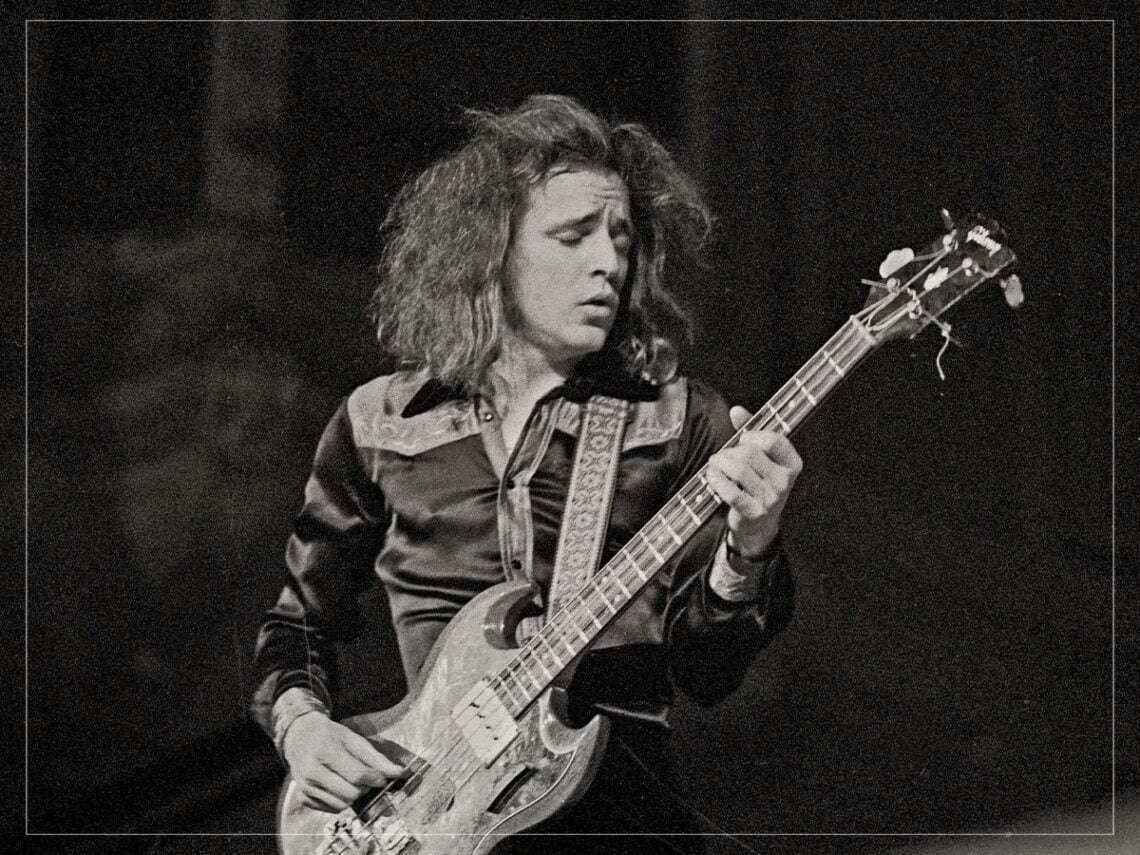

(Credits: Far Out / Heinrich Klaffs)

Wed 3 December 2025 18:30, UK

There are probably about three bands that immediately spring to mind when considering the archetypal supergroup, Cream invariably flashing first.

It’s a tag that likely rolled eyes within the power trio, but Cream indeed stands shoulder to shoulder with the likes of Bad Company and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young as the ultimate alloyed musical force.

It was hard to fail. Having hopped from The Yardbirds to John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, Eric Clapton’s electric blues guitar awaited the alchemic rhythms shared between The Graham Bond Organisation’s Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker’s respective bass and drum magic.

Adding a fuzzed-out pedal attack and an air of spontaneity to their live improv, Cream found themselves a leading, if slightly diffident, force of the counterculture’s psychedelic revolution. Powering through as a three-piece from 1966, a string of acclaimed albums and a live reputation for mammoth virtuosity ran on intensity with little hopes of enduring longevity.

Three years and albums later, the Cream machine was starting to wear and tear. Despite the grinning cover on 1969’s fourth and final Goodbye, the former creative vim had ebbed, the final LP barely eked out from a band who had virtually already broken up, plumping its tracklist with live cuts around the otherwise fantastic numbers like ‘What a Bringdown’ and the George Harrison co-write ‘Badge’.

Grievances and tensions between Bruce and Baker were flaring up too, the pair’s fiery relationship rendering any possible further Cream output untenable.

An artistic dead end had been reached. Eager to look beyond the confines of the Cream set-up, thoughts were had within the trio of looking ahead to the next musical venture. “Just simply because Eric and myself thought we had done as much as we could with that band at that time,” Bruce recollected to journalist Larry Katz in 1993, reflecting on Cream’s disbandment.

“We wanted to move on and do other things,” he added, “I wanted to work with a larger group. My first solo record had four or five horns and things like that. That was the simple reason. We’d gone as far as we could at that point with the trio format and three guys. Simply that.”

Bruce had his eyes on the musical shaping of his youth long before Cream’s rock vanguard. Coming from a blues and jazz background and a student of classical and Scottish folk, Bruce sought to explore such terrain on 1969’s Songs for a Tailor, his solo debut but second to be recorded after the instrumental Things We Like. His jazz-rock leanings had reared their head two years earlier, the sketches of ‘Weird of Hermistan’ and ‘The Clearout’ swept aside from Disraeli Gears’ final tracklist from the Atlantic label bigwigs.

Bruce would continue to flourish if keeping a lower profile than Clapton’s 1970s solo run and Baker’s hellraising rock mythos. Throwing himself behind many a production work and numerous session works from then on, the Cream shackles shaken off opened up a new creative and professional vista for Bruce to embrace a chequered career, a more myriad and intriguingly haphazard body of work than his erstwhile Cream comrades.

Related Topics