For over two decades, cosmologists have believed that the universe is expanding at an accelerating pace, driven by a mysterious force called dark energy. This assumption has shaped modern theories of cosmic evolution and underpinned the prevailing model of the universe: ΛCDM. But a striking new study is now challenging that foundational idea.

Researchers at Yonsei University in South Korea have identified a significant bias in the way astronomers measure cosmic expansion using type Ia supernovae, the stellar explosions long considered “standard candles.” Their analysis shows that these supernovae are not as uniform as previously assumed—their brightness varies depending on the age of their host galaxies.

A brief schematic diagram of the origin and evolution of the universe according to the standard cosmological model ΛCDM. Credit: Astronuclphysics

A brief schematic diagram of the origin and evolution of the universe according to the standard cosmological model ΛCDM. Credit: Astronuclphysics

This age-dependent brightness skews measurements of cosmic distances, particularly at high redshifts where younger galaxies dominate. Correcting for this bias, the researchers found no evidence of an accelerating universe. In fact, the data suggest that the expansion may already be slowing down.

Supernovae May Not Be So Standard After All

For decades, type Ia supernovae have played a critical role in measuring the universe’s expansion rate. Their peak brightness was believed to be consistent regardless of where or when they occurred, allowing astronomers to use them to estimate how far away a galaxy is. The further away, the dimmer the explosion appears.

This assumption formed the basis of the 1998 discovery that the universe’s expansion was accelerating—a breakthrough that led to the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics.

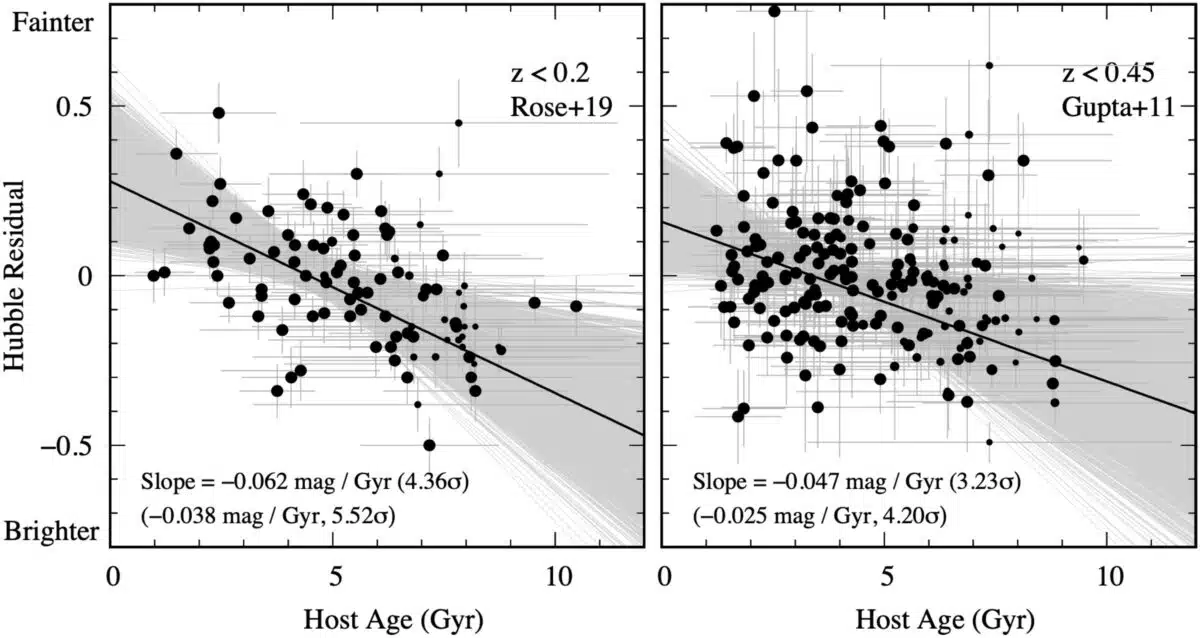

But in this new research, published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, led by Dr. Chul Chung and Junhyuk Son, the team analyzed over 300 supernova-hosting galaxies and found a clear correlation: the younger the galaxy, the dimmer its supernovae. Distant galaxies, which are typically younger, therefore produce explosions that appear fainter—not necessarily because they are farther away, but because of this age effect.

Correlation between SN Ia Hubble residuals and host-galaxy population age using updated age measurements. Both the low-redshift R19 sample and the broader G11 sample show a consistent trend: older hosts produce brighter SNe Ia after standardization, confirming the universality of the age bias. Credit: Chung et al. 2025

Correlation between SN Ia Hubble residuals and host-galaxy population age using updated age measurements. Both the low-redshift R19 sample and the broader G11 sample show a consistent trend: older hosts produce brighter SNe Ia after standardization, confirming the universality of the age bias. Credit: Chung et al. 2025

When this progenitor age bias was accounted for, the apparent evidence for accelerated expansion vanished. The findings suggest that much of what has been interpreted as dark energy’s influence could in fact be the result of uncorrected stellar evolution effects.

This isn’t an isolated claim. Separate observations from the Dark Energy Survey (DES), which examined 16 million galaxies, have already shown tension with the ΛCDM model. In combining baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) measurements and supernova data, DES scientists found potential signs that dark energy may not be constant.

Dr. Santiago Avila, a researcher involved in the DES BAO analysis, said in that report: “We can observe the cracks in ΛCDM, which is considered the standard model of cosmology.”

An Evolving Dark Energy Model Gains Ground

The implications of these findings run deep. After correcting for the age bias, the Yonsei team ran their data against several cosmological models. The standard ΛCDM framework—where dark energy is a constant—no longer matched the observations. Instead, their results aligned with a more flexible model: w₀waCDM, which allows dark energy to evolve over time.

Their calculations revealed a positive deceleration parameter, indicating that the universe’s expansion is not speeding up, but rather entering a slowing phase. This directly contradicts the foundational conclusion of accelerating expansion and pushes cosmologists to consider a different path forward.

Notably, this revised interpretation also offers a plausible explanation for the long-standing Hubble tension—the discrepancy between two primary methods of measuring the expansion rate of the universe. One method uses cosmic microwave background (CMB) data, while the other uses the distance ladder method involving supernovae and Cepheid variables.

Hubble image of the famous Type Ia supernova 1994D in the galaxy NGC 4526. This may not be as common anymore. Credit: NASA/ESA, the Hubble Key Project team, and the High Redshift Supernova Research Team

Hubble image of the famous Type Ia supernova 1994D in the galaxy NGC 4526. This may not be as common anymore. Credit: NASA/ESA, the Hubble Key Project team, and the High Redshift Supernova Research Team

The new study suggests that unaccounted-for age differences between galaxies used in the two methods may partially explain this mismatch. If supernovae in younger galaxies are systematically dimmer, their distances—and therefore expansion rates—would be misjudged.

Bigger Telescopes, Bigger Answers

Testing this theory requires more data, and that’s exactly what the next generation of sky surveys is poised to deliver. The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, through its Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), is expected to collect observations of over 20,000 supernova-hosting galaxies in the next few years. This sample size—almost 100 times larger than current datasets—will offer the statistical power needed to confirm or refute the Yonsei team’s claims.

Crucially, LSST will allow astronomers to isolate supernovae in galaxies of uniform age, removing the age bias at its root. If the corrected supernovae data continue to point toward a decelerating expansion, it would deliver a devastating blow to the long-accepted view of a dark energy-driven universe.

The European Space Agency’s Euclid mission, launched in 2023, is another key player. Designed to map the geometry of the dark universe using gravitational lensing and galaxy clustering, Euclid’s findings will help verify whether dark energy is a static property of space or a dynamic phenomenon that evolves over time.

Together, these missions promise to transform cosmology from a discipline grounded in assumptions into one that tests every foundation.