What is Devolution?

“Devolution is the transfer of power from a central government to subnational (e.g., state, regional, or local) authorities. Devolution usually occurs through conventional statutes rather than through a change in a country’s constitution; thus, unitary systems of government that have devolved powers in this manner are still considered unitary rather than federal systems, because the powers of the subnational authorities can be withdrawn by the central government at any time” – Charles Hauss, Britannica

This explainer aims to provide an overview of the history of devolution in the United Kingdom, what devolution looks like today, and lessons that can be taken into the Irish context. It is important to note that there are different levels of devolution. The most well-known would likely be the move from centralised government in Westminster to the establishment of three elected institutions within the countries of the UK in the late 1990s. These are the Scottish Parliament, the Senedd (National Parliament in Wales), and the Northern Ireland Assembly. In addition to this, devolution can be considered in the work of directly elected mayors in regions of England, noting that Ireland now has its first directly elected Mayor in Limerick, since June 2024.

Devolved Institutions in the UK

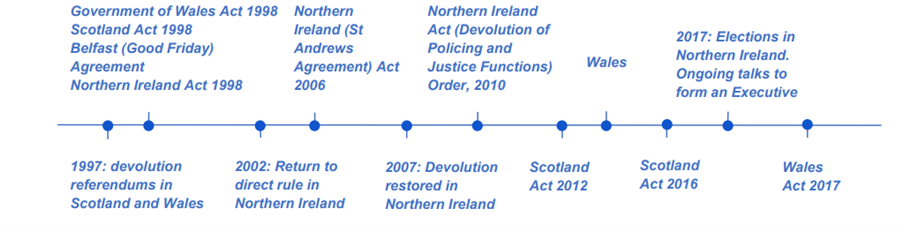

Figure 1. UK Devolution Timeline, UK Government Website, Devolution Factsheet

Scotland

The Scotland Act of 1978 was put forward by the Labour government of the time which would create a Scottish Assembly. A referendum was held in March 1979, in which 40% of the Scottish electorate was required for the creation of the devolved parliament to go ahead. Only 33% of the electorate voted in favour, followed by a vote of no confidence in the Labour government, which resulted in the Act being thrown out. In 1997, a second referendum was held proposing the establishment of a devolved government in Scotland, this resulted in the Scotland Bill being passed in the UK parliament and thus the Scotland Act came into effect in November 1998.

The Scottish Parliament sits at Holyrood in Edinburgh with 129 elected Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs). Prior to devolution, Scotland already had its own legal and education system, and since the Scotland Act in 1998 , the Scottish Parliament has become responsible for other areas including agriculture, forestry and fishing; environment; health; housing; justice; local government; some transport; and taxes including income tax, stamp duty, and air passenger duty; and finally, some of welfare.

Wales

A referendum to create a devolved Welsh Assembly was rejected on St David’s Day in 1979. From 1979 to 1997, there was a change in public opinion underpinned by economic difficulty and disillusion with the Conservative government at the time, which led to a second referendum in 1997 following Labour’s victory in the general election. The referendum was passed by just under seven thousand votes, thus forming the National Assembly of Wales. The Government of Wales Act was passed in the UK parliament in 1998, which established the legal framework for the Assembly.

In 2020, the National Assembly changed its name to Senedd Cymru (the Welsh Parliament) to reflect its constitutional status. Sitting at Cardiff Bay in Wales, the Senedd Cymru is currently made up of 60 elected Members of the Senedd, but this is set to change in 2026. After the general election in May 2026, the Senedd will have 96 Members instead of 60, with a new voting system, new constituencies, and new rules in place for the upcoming election. The Senedd will remain responsible for agriculture, forestry and fishing; education; environment; health and social care; housing; local government; highways and transport; parts of income tax, stamp duty and landfill tax; as well as the Welsh language.

Northern Ireland

In the case of Northern Ireland, devolution is slightly more complex given the context in which it occurred. Devolution was a key component of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement and saw the establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly and the Northern Ireland Executive. Government powers are divided into three categories:

“[…] reserved, excepted and transferred. When fully functioning, the Northern Ireland Assembly can make primary and subordinate legislation on “transferred” matters; on “reserved” matters with the consent of the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland and, in limited circumstances, on “excepted” matters.”

Excepted matters include the constitution; Royal succession; international relations; defence and armed forces; nationality, immigration and asylum; elections; national security; nuclear energy; UK-wide taxation; Currency; conferring of honours; international treaties.

Reserved matters include firearms and explosives; financial services and pensions regulation; broadcasting; import and export controls; navigation and civil aviation; international trade and financial markets; telecommunications and postage; the foreshore and seabed; disqualification from Assembly membership; consumer safety; intellectual property.

Transferred matters include health and social services; education, employment and skills; agriculture; social security, pensions and child support; housing; economic development; local government; environmental issues, including planning; transport; culture and sport; the Northern Ireland Civil Service; equal opportunities; and justice, prisons and policing.

The Northern Ireland assembly sits in Stormont in Belfast and consists of 90 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs). As David Torrences explained in his briefing on devolution in Northern Ireland, the devolved assembly in Northern Ireland has been more unstable than in other parts of the UK and so, the UK government has been ‘in charge’ on devolved matters in periods when the Executive was non-functioning.

Devolution in England

In England, devolution refers to the transferring powers from central government to local governments, including local and combined authorities. Probably most well-known are the 10 directly elected mayors of combined authorities across England, referred to as ‘Metro Mayors’.

Two such mayors, Andy Burnham and Steve Rotherham, Mayor of Greater Manchester and Mayor of Liverpool City Region respectively, visited the IIEA in February 2025 to discuss their roles, and the importance of such devolution for areas outside of countries’ capitals, particularly for England. Mayor Rotheram described, “devolution is a journey and we’re [Liverpool] not at our destination at the moment” but that in his role he has been able to create job opportunities, build more housing, and “transform the transport system”. In his remarks, Mayor Burnham highlighted the importance of having devolved power when it comes to transport, like in Manchester, because “it is the foundation for a productive economy and economic growth and allows people to connect with each other and to their jobs”.

The first metro mayor was elected in London in 2000. Since then, and under the Local Government Act 2000, 13 local authorities have elected mayors, and under the Cities and Local Government Devolution Act 2016, 11 metro mayors have been directly elected, with an election for the mayor of Suffolk and Norfolk set to take place in May 2026. The main difference between the two categories of mayors is that metro mayors have more power when it comes to creating plans to boost the economy of the area and in plans for housing and transport, while local authority mayors form one of the available types of ‘political management arrangements’ available to local authorities in England and Wales. Mayors can be elected at this level in England and Wales, but there is no legislative power to do so in Scotland or Northern Ireland.

The Future of Devolution & Lessons for Ireland

This leaves the question of what the future of UK devolution looks like. Mayors Burnham and Rotheram call for a “complete rewiring of Britain” in their book Head North, however it is important to note that it is not necessarily a ‘one size fits all’ solution. Since the evolution of devolution in the UK began in the early 20th century, its functions have changed to suit a modern-day world. The likes of metro mayors and their individual leadership qualities can make them true representatives of championing devolution at local and combined authority level in the UK.

In Ireland, with a highly centralised government sitting in Dáil Eireann in Dublin, devolution is not well established. Mayor of Limerick John Moran is the first ever directly elected mayor in Ireland. This change came about in 2019 when the electorate in Limerick voted in favour of a directly elected mayor. At the same time, the proposal was rejected in Cork and Waterford. As the first Mayor in Ireland with executive powers, the mayor’s office will cover strategic planning; housing strategy; road transport; and the environment. It remains to be seen, if the mayor’s office has the resources to act on these portfolios or whether such a highly centralised government will allow for the mayor to make substantial changes. In Ireland’s Programme for Government: Securing Ireland’s Future, it is stated that one of their priorities is to “support the office of the Directly Elected Mayor of Limerick and consider further plebiscites in Dublin and other cities.” It remains to be seen if this is something that could work in other counties, particularly in Dublin, where the county falls into 4 different local authorities. Perhaps, devolution of this kind could help reduce the rural-city divide that presents itself outside of Ireland’s main cities and could restore confidence in politics, unlocking more accountability within local authorities.

Democratic Resilience Through Devolved Power

Revitalising democracy is important now, more than ever, as democracies come under threat across the EU and the US, devolved institutions and local authorities can play a key role in counterbalancing such democratic backsliding. In their book, How Democracies Die, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblat highlight that democratic decline often begins when institutions fail to check concentrated power. By distributing authority and empowering local governance, devolution can revitalise democratic norms and citizens’ trust.

Overall, the evolution of devolution in the UK is complex and varies across different levels. From national parliaments/assemblies with varying degrees of powers given to those directly elected by the electorate, to mayors of local and combined authorities, it is clear that the overarching priority is to make sure that people are connected i.e. to each other, to their jobs, and that their national/local governing bodies can reflect the needs of the people i.e. through housing, economic development, and transport.

“Devolving real power to communities across the country represents the best hope of restoring people’s confidence in the political system. It is not a panacea in itself but it could go a long way in helping to heal the rifts that divide our society.” – Mayor Steve Rotheram.