Folklore photography began in Japan with Haga Hideo, who made a career of recording human activities and customs on film. His distinctive style of establishing rapport with his subjects was an approach he learned from colleagues conducting fieldwork. A folklore researcher studying the connection between ethnography and photos describes how Haga’s career was born.

Fieldwork and Photography

The photographs Haga Hideo (1921–2022) took during fieldwork in Kagoshima Prefecture’s Amami Islands over a period of three years in the 1950s marked a definitive moment in Japan’s humanities field. The Amami study, in the immediate postwar period when the islands formed Japan’s southernmost boundary before Okinawa reverted to Japanese rule in 1972, were a way of reexamining the concept of “Japan” after the loss of its overseas colonies.

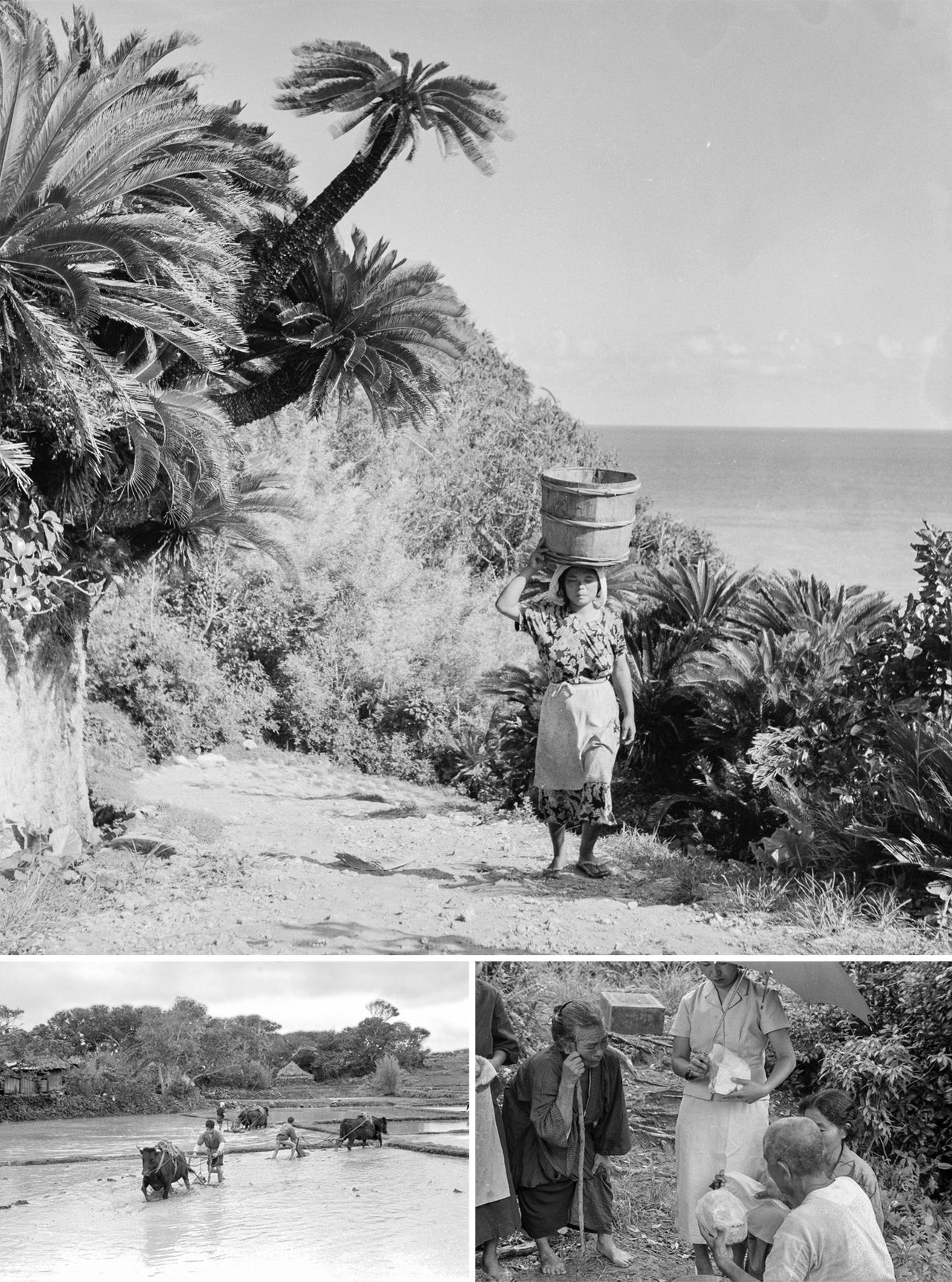

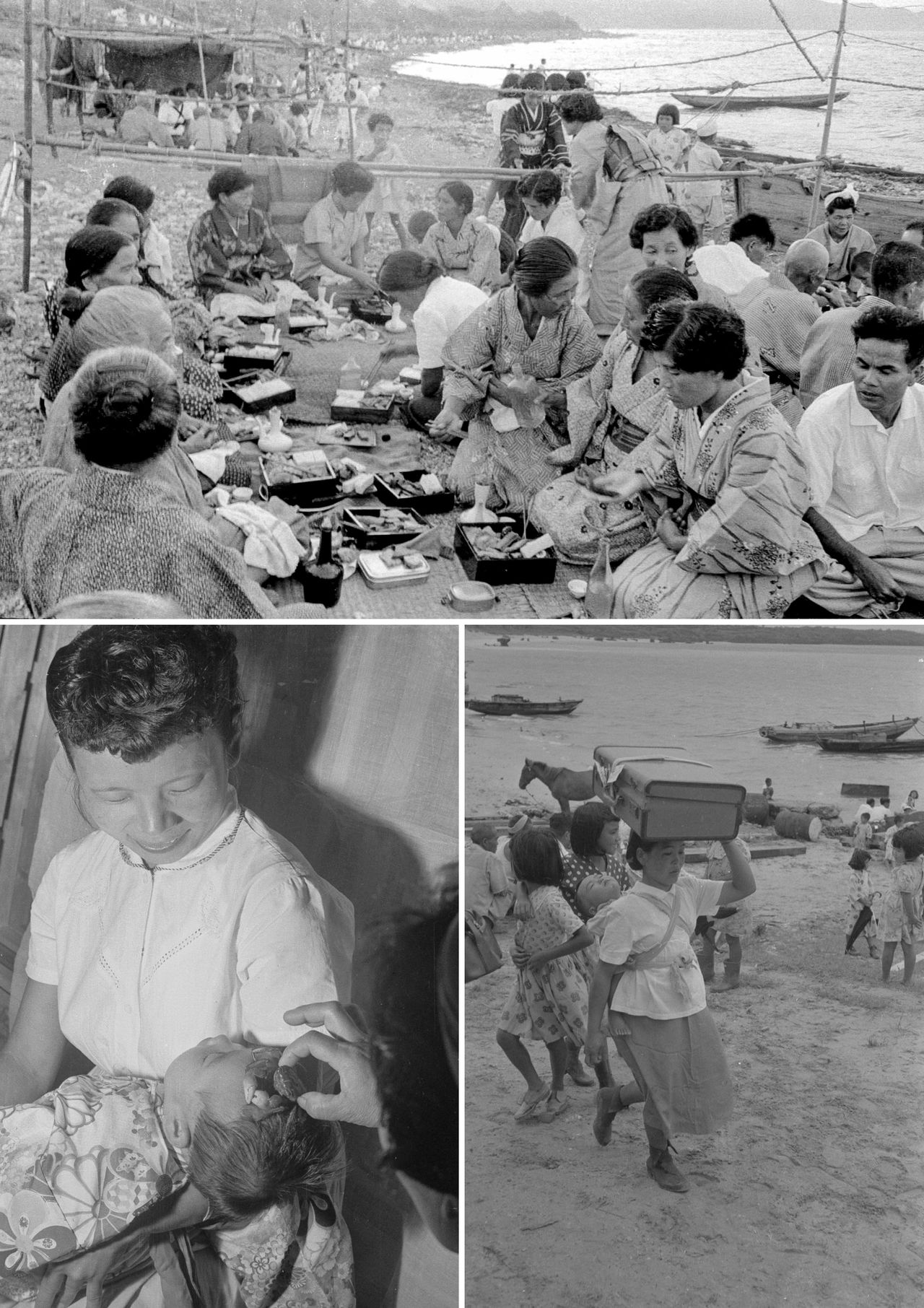

As the country entered its era of rapid economic growth in the postwar years, the premodern way of life was still prevalent in the Amami Islands, which had just been returned to Japanese rule: homes with thatched roofs, granaries elevated on stilts, women carrying loads on their heads, burials by exposure to the elements, and ritual bone collecting and washing. To study the relationship between native Yamato culture and South Asian culture, Haga traveled to Amami with a group of scholars. Inspired in his student days by lectures given by the ethnologist and folklorist Orikuchi Shinobu (1887–1953), Haga had developed an interest in folklore. On his own, he learned techniques for photographing folk customs, an experience that led him on the path to becoming a chronicler of Japan’s folklore and folkways.

Clockwise from top left: An islander with a bucket on her head; washing the bones of the dead; oxen plowing rice paddies. (© Haga Hideo)

Since the birth of photography in the West in the early nineteenth century, photos have been a medium for recording people, places, and things all over the world. But in field sciences like folklore studies and ethnology, which study people’s lives—how they live, and their work, celebrations, and entertainment—it took some time before photography could be utilized to keep a visual record, since bulky equipment and light sensitivity issues made it difficult to closely focus on people’s daily doings.

The anthropologist and ethnologist Torii Ryūzō (1870–1953) roamed over the prewar Japanese empire—including China, Taiwan, Korea, and Sakhalin—in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In Japan, he became the first person ever to use photos in fieldwork, despite the difficulties of having to carry heavy equipment and fragile glass photographic plates. Although cameras began to be used in academic studies after 1925, when the first made-in-Japan cameras appeared, this was not common practice. And by the late 1930s, the country had been placed on a war footing and anyone conducting fieldwork near the border or military facilities was considered to be spying.

An Early Postwar Amami Study

Fieldwork started up again in earnest when restrictions were lifted after World War II, and cameras were eagerly adopted. With imports of photographic equipment from abroad resuming and the revival of the domestic camera industry, photography began to be used extensively.

One notable example of fieldwork was the joint studies carried out by the Federation of Nine Learned Societies. Started by the financier and folklorist Shibusawa Keizō (1896–1963), this grouping, which counted the Anthropological Society of Nippon and the Japan Sociological Society among its members, aimed to establish a cross-disciplinary federation. Modeled on American-style area studies, the Federation conducted extensive studies on the island of Tsushima, Nagasaki Prefecture, in 1950 and 1951, and in Ishikawa Prefecture’s Noto Peninsula in 1952 and 1953. The site selected for the third study was the Amami Islands, which had only been returned to Japanese sovereignty in December 1953.

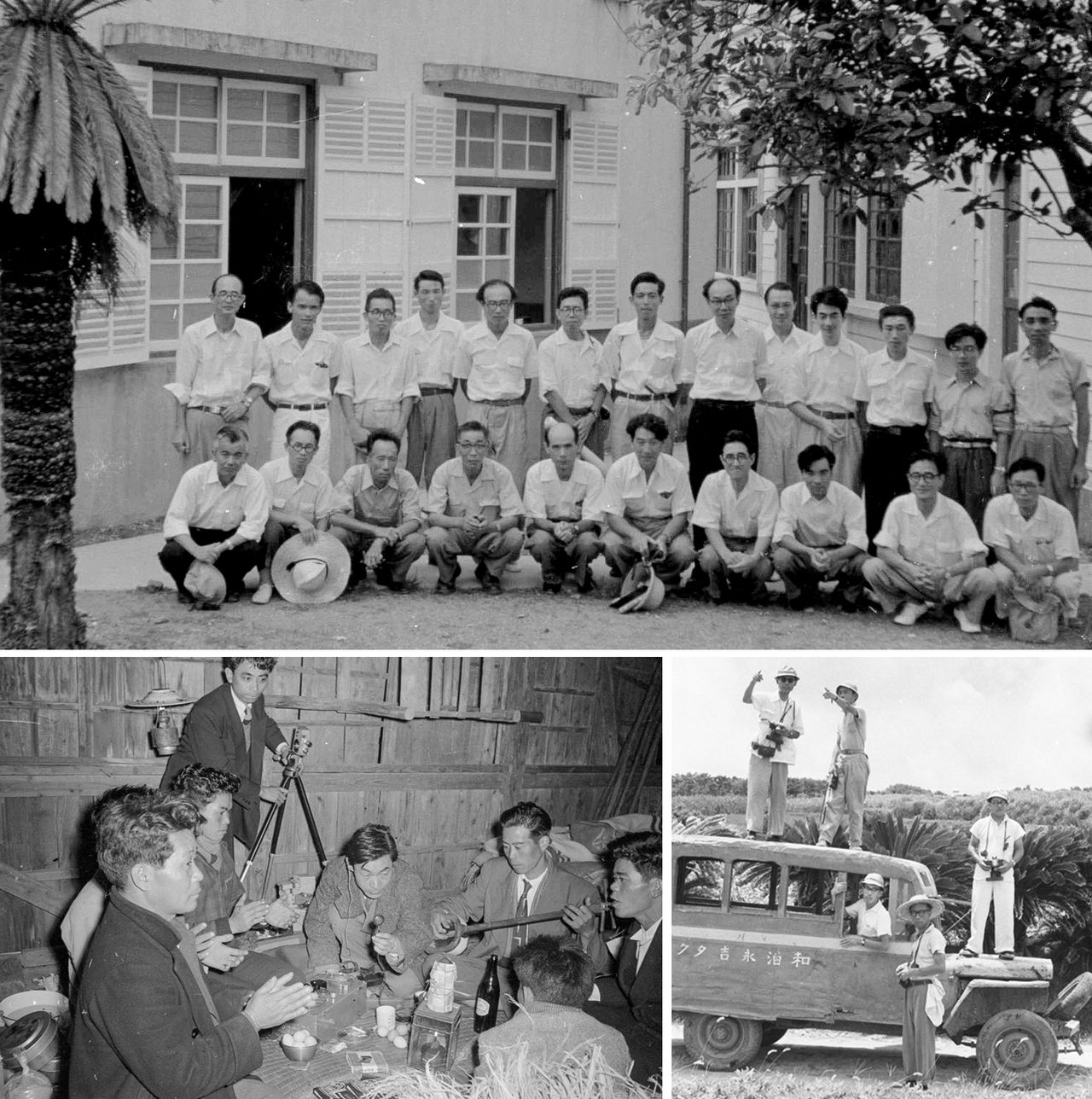

The folklorist Seki Keigo (1899–1990) led the Amami study, which took place from 1955 through 1957. He suggested having a photographer accompany the group, and Haga was the individual selected. Haga spent a total of 182 days on Amami over the three years, working together with researchers and perfecting his technique for photographing folk culture.

The Federation of Nine Learned Societies research team on the Amami Islands. In the group photo, Haga stands at far right in the back row. (© Haga Hideo)

Shodonshibaya, a local form of kyōgen comic drama on Kakeromajima. It was performed for the research team for the first time after the war. (© Haga Hideo)

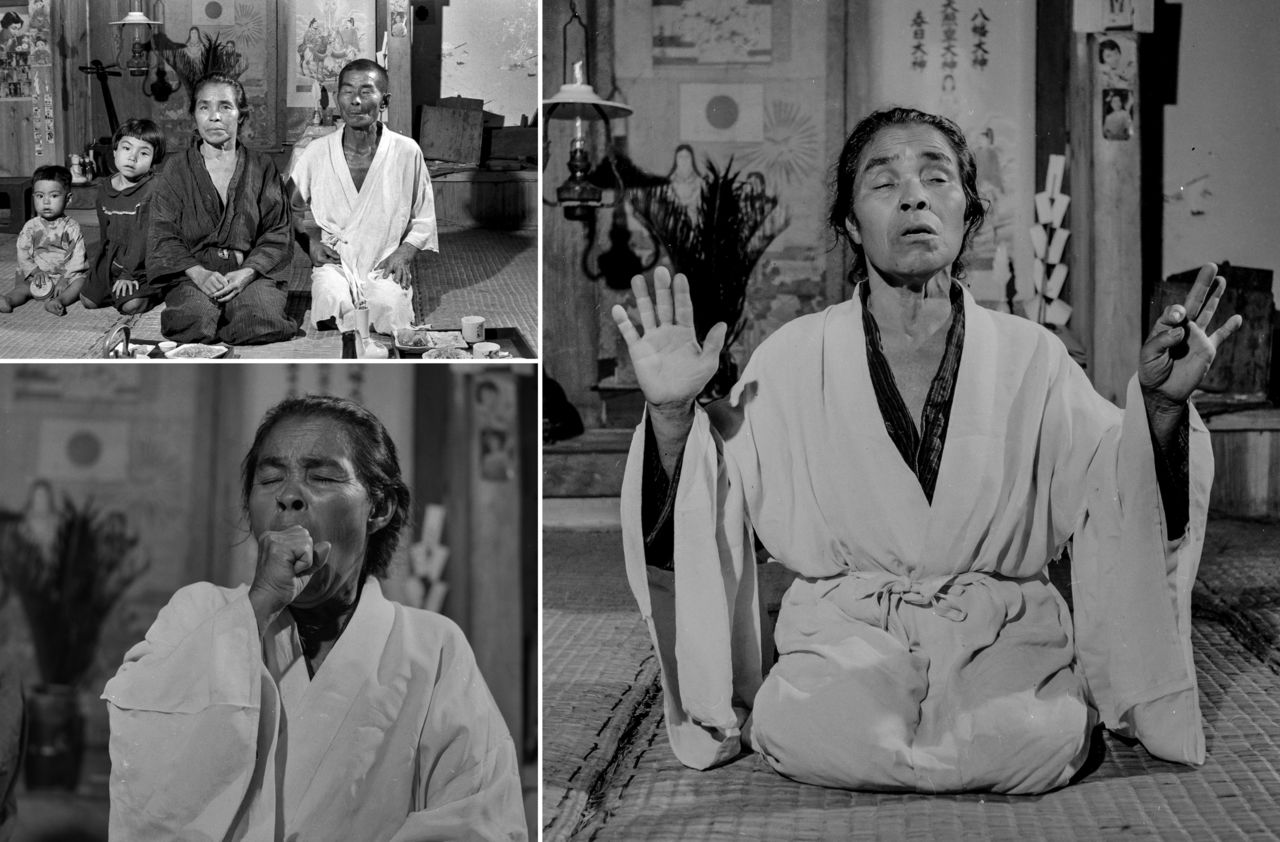

Scientific Research Methods

Notably, Haga learned the participant-observation method, where researchers live among the people they are studying. Relating his experiences photographing noro priestesses and yuta shamanesses, collectively called miko, he related the advice he received from young researchers. “I was told that the miko dislike men, so that I should start by photographing the men of the family going about their daily tasks, and then to photograph the family’s children. After a month of this, the women would have gotten used to me and would no longer be puzzled by my presence.” He finally succeeded in photographing a yuta who had been invited to a family’s ancestor ceremony. Not only was he able to capture the moment she was possessed by a spirit, but the family even described the rite taking place.

During participant observation, the ability to establish rapport between the researchers and the people they are studying is crucial for the quality of the data obtained. Haga learned how to build rapport through his photography.

These photos taken on Okinoerabujima show a yuta performing a secret ceremony; her yawn (at lower left) indicates the moment of spirit possession. (© Haga Hideo)

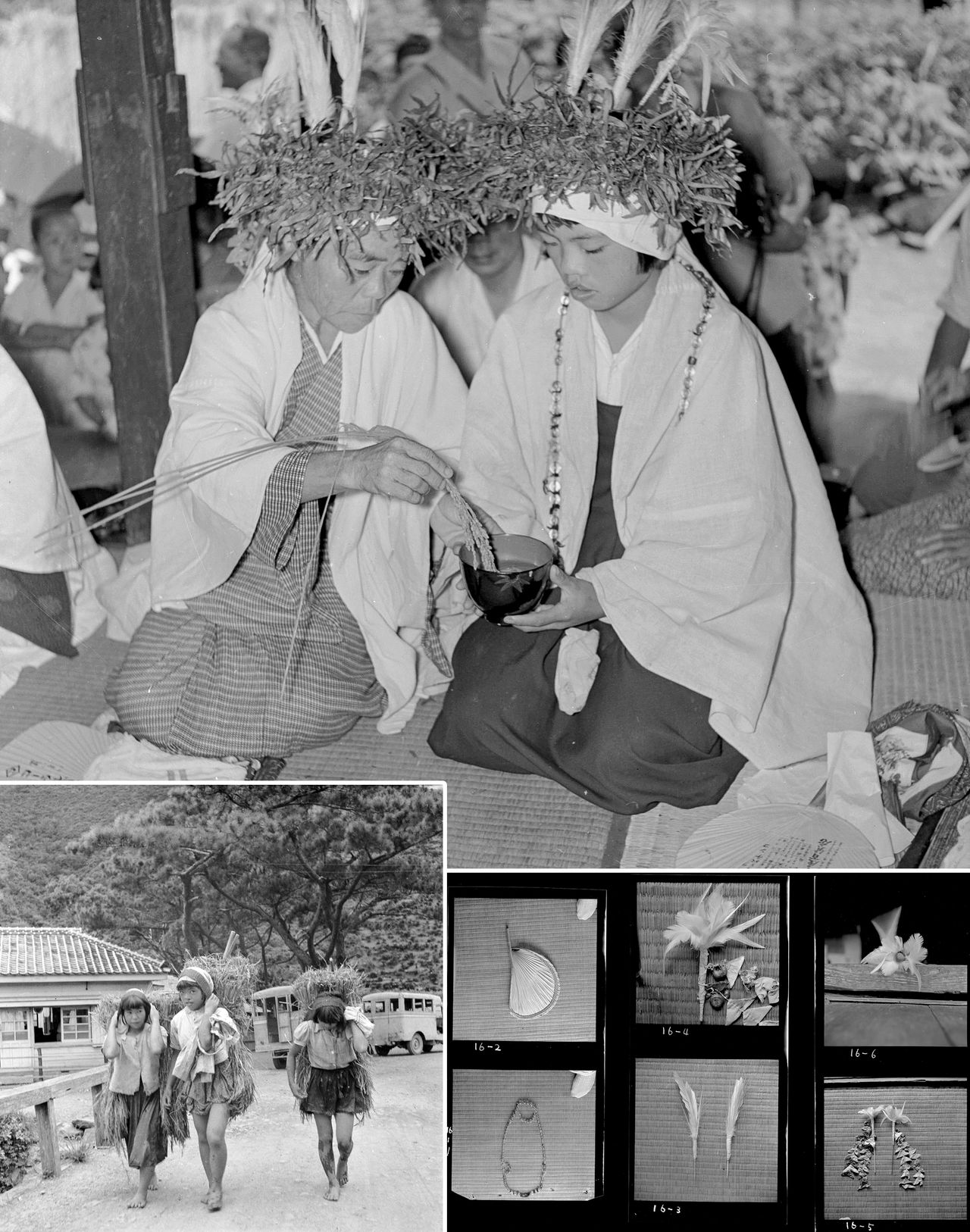

Noro are shown praying for a bountiful harvest on Amami Ōshima. Haga’s photos also tracked the daily life of young noro and documented how ceremonies proceeded and the ritual implements they used. (© Haga Hideo)

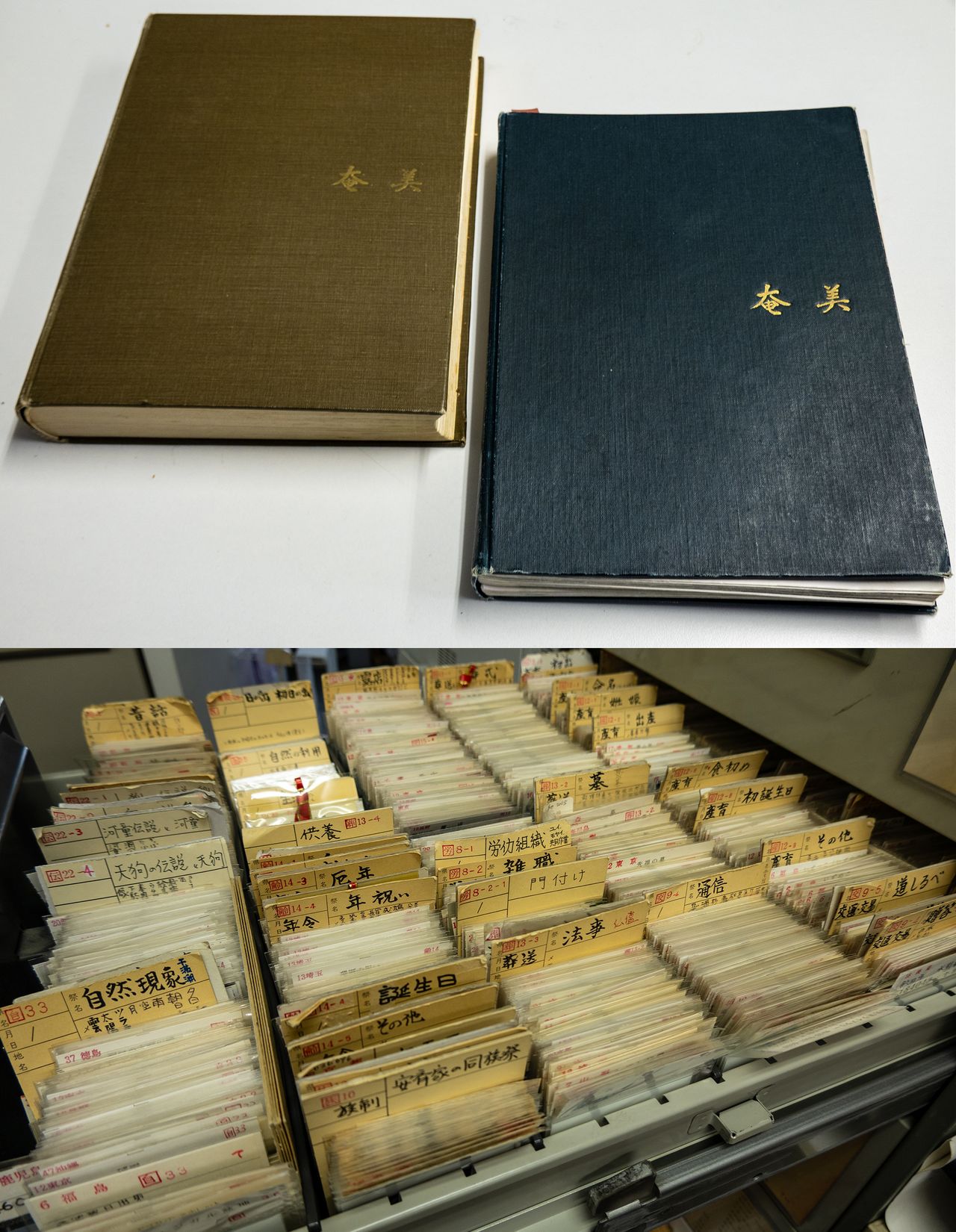

During the Amami study, Haga also learned how to classify his work. The roughly 30,000 photos the research team took were organized with the Human Relations Area Files method developed mainly by Yale University researcher George Murdock (1897–1985). Murdock created this method during World War II to process national strategic information, achieving a system that later made it possible to classify, preserve, and access ethnographic materials on a global scale.

In 1959, the Amami study report was published in two volumes, one of photos and the other of scholarly papers on the field research. This publication was the only photographic record of a study in the nearly 50 years of the Learned Societies’ activities. Of the 770 photos in the record, 562 were taken by Haga; the book is essentially a collection of his photos.

Through this experience, Haga learned the importance of classification as a means of identifying the topics of the photos. At the same time, he broadened the scope of his photography from seasonal events to the daily lives of the people whose photos he took.

Scenes of ceremonies, life milestones, and everyday life. (© Haga Hideo)

Top: The book of photos compiled for the Learned Societies’ field study, in 12 chapters by topic. Bottom: Photos stored at Haga’s office, filed according to his own classification method. (© Nippon.com)

The classification method also provided an unintended benefit for Haga’s business. Tagged according to topic and location, Haga’s photos could be located swiftly and accurately whenever advertising or media companies requested material. The organization and classification of the photo stock owed much to the perseverance of Haga’s wife, Kyōko. She knew what the market wanted and sometimes directed Haga to take photos on specific themes. Although photographers taking photos of folk customs were not rare, not many of them were able to respond in the way that Haga did. Haga established the folklore photo genre, and this is where the true value of his status as a giant in the field lies.

The Amami study was the starting point for Haga’s career. In the summer of 2025, digitalization of all his film was completed, and his son Hinata, a photographer himself, donated the collection to the Amami Island communities. Haga’s principal works had been donated and exhibited on Amami during his lifetime, but the digitalized collection now makes it possible to see the photos as they were shot, in sequence, giving a clearer understanding of conditions at the time. The collection’s value as documentation will no doubt increase as it leads to new discoveries and insights into vanished ways of life.

Top: Haga Hinata (second from right) presented the digitalized record of the Amami study to the city of Amami. Bottom: Local photos were also presented to the Okinoerabu towns of China and Wadomari. They were used for a photo exhibition and printed in the towns’ community newspapers. (© Nippon.com)

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner photo: Farming and fishing in Amami Ōshima in the 1950s. © Haga Hideo.)