Sound is energy carried by vibrations moving through matter. It is something we hear, not something we expect to lift, hold, or precisely control physical objects.

And yet, for decades, scientists have been doing exactly that.

By carefully shaping intense sound waves, researchers have learned how to suspend droplets, particles, and small solids in mid-air. The technique, known as acoustic levitation, uses high-frequency sound to counteract gravity and hold matter in place without physical contact.

Early hints of acoustic levitation appeared in the 19th century, when experiments such as Kundt’s tube showed that sound waves could trap particles at specific points in space, even though the goal was simply to measure the speed of sound.

At the time, however, the scientists had failed to realize that they had accidentally found a way to make matters float. They recognized its significance in the 1930s, when liquid droplets were first levitated using ultrasonic waves.

What is acoustic levitation?

Acoustic levitation, also known as sound levitation, is a technique for suspending matter in air against gravity and without physical contact, using acoustic radiation pressure from high intensity sound waves, most commonly ultrasound.

Sound is a mechanical wave that propagates through a medium, such as a gas, liquid or solid, by causing particles to oscillate and transmit energy through the material. When these waves are strong enough, they exert a measurable force on matter known as acoustic radiation pressure.

In practice, a transducer emits ultrasonic waves that travel through air and reflect back toward the source. The interaction between the incoming and reflected waves creates a standing wave, which contains alternating regions of high and low pressure, known as antinodes and nodes.

Small objects placed within this field naturally migrate toward the low-pressure nodes, where the upward acoustic force can counteract gravity. As long as this balance is maintained, the objects remain suspended in mid-air.

The clumping problem

Because acoustic radiation pressure depends on sound rather than magnetism or light, the method can be used on a wide range of materials like liquids, powders, biological tissues or even fragile solids.

But the same wave interactions that enable levitation generate secondary forces between nearby objects. This causes multiple particles to drift toward one another and clump together. Generated by the sound field itself, these attractive forces have so far made it difficult to control more than a single particle precisely.

A new, breakthrough approach developed by physicists at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) has now overcome this obstacle by adding electric charge to the levitated objects.

University of Chicago and the University of Bath scientists revealed new insights about how materials cluster together in the absence of gravity. Credit: Courtesy of Melody Lim

University of Chicago and the University of Bath scientists revealed new insights about how materials cluster together in the absence of gravity. Credit: Courtesy of Melody Lim

The added charge introduces electrostatic repulsion, a fundamental force, which as described by Coulomb’s Law, prevents objects or particles with the same type of electric charge (two negatives or two positives) from clumping together.

It therefore enables stable, multi-object control. This means several objects can float separately within a single acoustic field, opening the door to more complex, contact-free experiments and applications.

“By counteracting sound with electrostatic repulsion, we are able to keep the particles separated from one another,” Sue Shi, a PhD student and first author of the study, noted.

Adding charge to sound

The team at ISTA was initially trying to separate levitated particles so they would form crystals, or specific repetitive patterns. However, in doing so, they realized that a more fundamental challenge stood in the way.

Known as acoustic collapse, the phenomenon causes particles to snap together in mid-air as sound-induced forces pull them toward one another. To overcome it, the team introduced electric charge into the system.

With the charge carefully tuned, the team found they could control how particles behaved within the acoustic field. Depending on the balance between the sound and the electrostatic forces, the particles could remain fully separated, collapse into clusters or form hybrid arrangements combining both states.

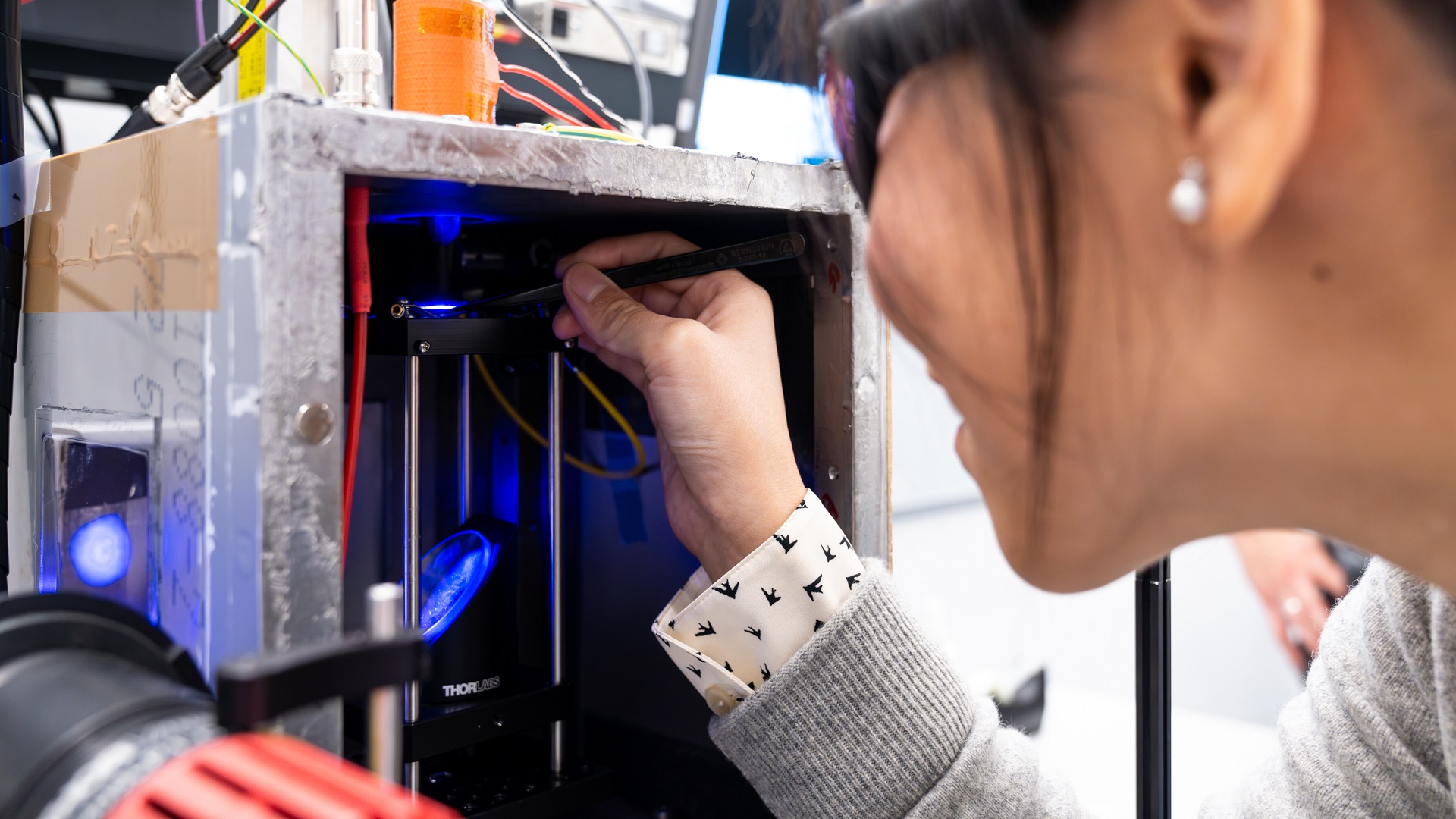

Sue Shi, ISTA PhD student, places a particle inside the acoustic levitation setup.

Sue Shi, ISTA PhD student, places a particle inside the acoustic levitation setup.

Credit: ISTA

The physicists could also bounce the particles off the levitation setup’s charged bottom reflector plate to switch between the different configurations. The added control revealed behaviors that had not been observed before.

While some particle arrangements began rotating spontaneously, others showed chasing or looping motions. These dynamics pointed to so-called non-reciprocal interactions, including effects that appear to violate Newton’s third law.

Although Newton’s third law was not violated the missing momentum was carried away by the sound field itself. “By introducing electrostatic repulsion, we can now maintain stable, well-separated structures,” Scott Waitukaitis, PhD, an assistant professor at ISTA, pointed out.

Overcoming acoustic collapse

Over the years, acoustic levitation has been applied across many fields, including the analysis of sensitive materials, pharmaceutical research, materials science and micro-assembly, where it is used to build complex structures and microchips.

Research carried out by UK’s University College London showed that it even has the potential to revolutionize virtual reality and 3D printing. The team levitated different objects including polystyrene beads, water and fabric.

By levitating and manipulating objects in real-world environments, the technique could enable interactive 3D displays without headsets and support new forms of 3D printing that move beyond today’s layer-by-layer, single-material approach.

In addition, scientists at the University of Bath and the University of Chicago have levitated particles to observe how materials cluster together when they are not resting on a hard, flat surface.

They said that apart from applications in soft robotics, the method could help reveal how planets begin to form. Anton Souslov, PhD, a physics professor at the University of Bath, said that ultrasound is used to make fine mist in humidifiers and to clean grime from hard surfaces.

Understanding how to control ultrasonic forces is key. “For us scientists, defying gravity to levitate dust also has this more fundamental interest of developing earth-based experiments to understand how bodies in space like planets and moons start to form when space dust begins to agglomerate together,” Souslov noted.

The ISTA team believes that their approach could be particularly useful in micro-robotics, as well as other areas that depend on assembling controlled, dynamic structures from small components.

“That’s the funny thing about experiments: the most interesting discoveries often come from the things that don’t go as planned,” Shi concluded in a press release.