In a new study published in The Open Journal of Astrophysics, scientists have unveiled a new mapping of the universe’s invisible components. By analyzing subtle distortions in the shapes of millions of galaxies, they have provided new insights into the nature of dark matter and dark energy—two of the most mysterious forces in the cosmos. This research challenges current models of cosmic structure and offers a deeper understanding of how the unseen shapes the visible universe.

The Invisible Universe Unveiled: Mapping the Dark Forces of Space

In the vast expanse of the universe, nearly 95% of the cosmos remains hidden from view, consisting of dark matter and dark energy—mysterious substances that scientists have been trying to understand for decades. Through the use of the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) and data from the Dark Energy Survey (DES), a new project has brought us one step closer to unlocking the secrets of these invisible forces. By studying faint distortions in galaxy shapes, researchers at the University of Chicago have made a significant breakthrough that helps refine our understanding of the universe’s large-scale structure. The study was published in The Open Journal of Astrophysics and introduces a new perspective on the interactions of dark matter, dark energy, and the ordinary matter we can see.

The Power of Gravitational Lensing

Gravitational lensing is a powerful technique used by astronomers to study the hidden mass in the universe. It occurs when the light from distant galaxies bends as it passes through the gravitational field of intervening cosmic structures. This bending of light allows scientists to measure the distribution of mass—both visible and invisible—across vast regions of the universe. In the case of this new study, weak gravitational lensing provided the key to understanding how matter is distributed on a cosmic scale.

Dhayaa Anbajagane, a PhD student at the University of Chicago and the lead analyst on the project, explained,

“Weak lensing measurements are best at probing the ‘clumpiness’ of matter. Quantifying this clumpiness sheds light on the origin and evolution of structures like galaxies and galaxy clusters.”

Through this method, researchers can map out the density of dark matter and better understand how it influences the formation of galaxies and other cosmic structures.

This approach is akin to studying the layout of a city by observing how people are spread out across different neighborhoods. The more densely packed areas reveal crucial information about how the “landscape” of the universe has evolved over time.

A New Dataset with Unprecedented Scope

Between 2013 and 2019, the Dark Energy Survey gathered a wealth of data, mapping the shapes of over 150 million galaxies across a significant section of the sky. The survey covered an area of about 5,000 square degrees—roughly an eighth of the sky—allowing scientists to study how dark matter and dark energy influence the cosmic landscape. With the recent addition of data captured beyond the original survey boundaries, researchers were able to nearly double the number of galaxies included in the analysis.

By combining the newly acquired data from the DECam with the original DES data, the research team was able to create a far more detailed and accurate picture of the universe. “We are also able to combine the DECADE lensing measurements with those of DES, resulting in a galaxy lensing analysis that uses the largest number of galaxies (270 million) covering the widest patch of sky (13,000 square degrees) to date,” said Anbajagane. This comprehensive dataset provides an unprecedented view of the universe, with enough precision to offer valuable comparisons to other cosmological models, including the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB).

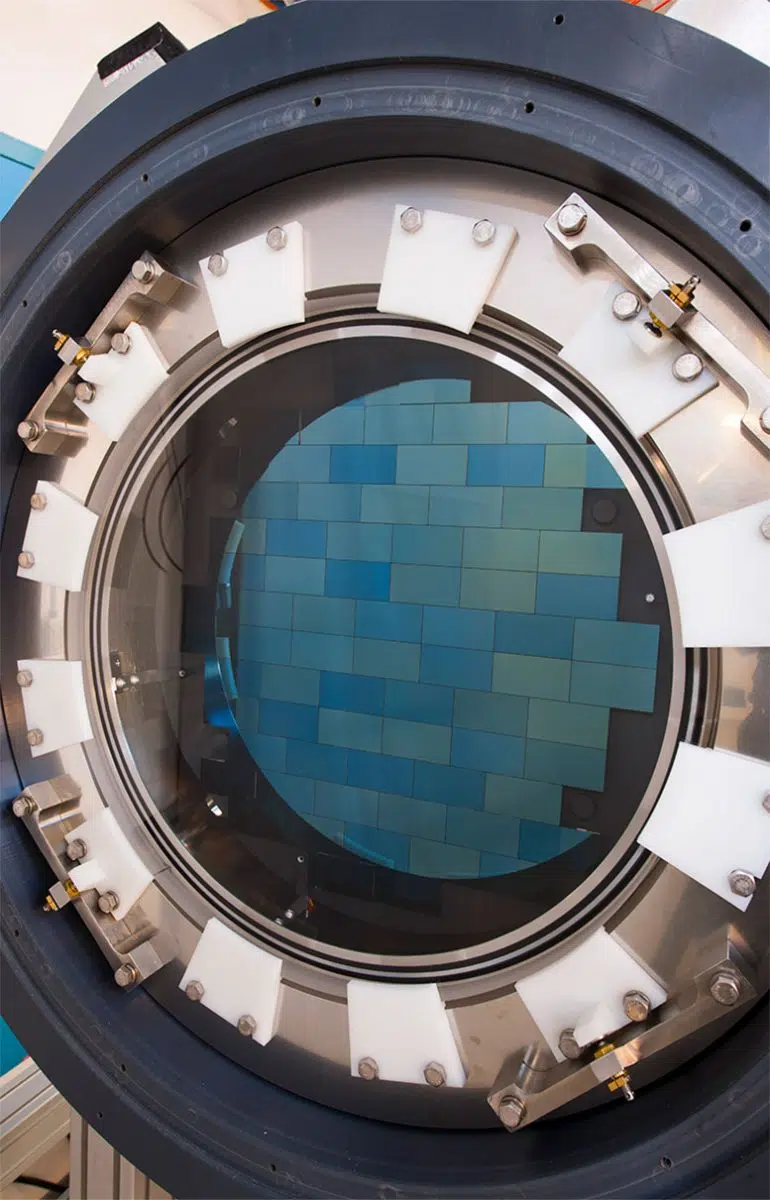

The Dark Energy Camera contains 62 ultra-sensitive CCD sensors and allows imaging of the universe with unprecedented depth. Credit: DOE/FNAL/DECam/R. Hahn/CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

The Dark Energy Camera contains 62 ultra-sensitive CCD sensors and allows imaging of the universe with unprecedented depth. Credit: DOE/FNAL/DECam/R. Hahn/CTIO/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA

The Role of Dark Energy and Dark Matter

Dark matter and dark energy play pivotal roles in shaping the universe, even though they cannot be directly observed. Dark matter exerts a gravitational influence on galaxies and galaxy clusters, helping to govern their formation and movement. Dark energy, on the other hand, is believed to be responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe. Together, these unseen forces account for most of the universe’s mass-energy content, yet they remain some of the most elusive and least understood components of cosmology.

This study is crucial for advancing our understanding of these mysterious forces. By mapping out how matter—both visible and invisible—is distributed, the researchers can gain insights into the broader dynamics of the universe. For example, the expansion of space is thought to be driven by dark energy, but the exact nature of this force remains unclear. Through the detailed mapping enabled by gravitational lensing, the study offers new clues that may help scientists refine existing theories or develop new models.

Repurposing Archival Data: A Unique Approach

One of the standout features of this study is the use of archival data in the analysis. Traditionally, weak lensing surveys require years of dedicated observations, with many images being discarded due to poor quality. However, the DECADE project took a different approach. Instead of focusing exclusively on lensing-dedicated imaging, the team repurposed images originally taken for a variety of scientific purposes, from studying distant galaxy clusters to examining dwarf galaxies.

“One unique result from this work has to do with choices we make on image quality,” said Anbajagane. “The DECADE project is unique as it repurposes archival data—images originally taken by the astronomy community for a wide variety of science goals—and uses significantly more permissive criteria for image quality. Our work shows robust lensing analyses can be done even if we do not have lensing-dedicated imaging campaigns.”

This innovative use of archival data opens new possibilities for future astronomical surveys, as it allows for more flexible and efficient data analysis. Instead of discarding potentially valuable images, astronomers can now make use of them in ways that were previously thought to be impossible.