(Credits: Far Out / Circacies / Alamy)

Sun 14 December 2025 18:00, UK

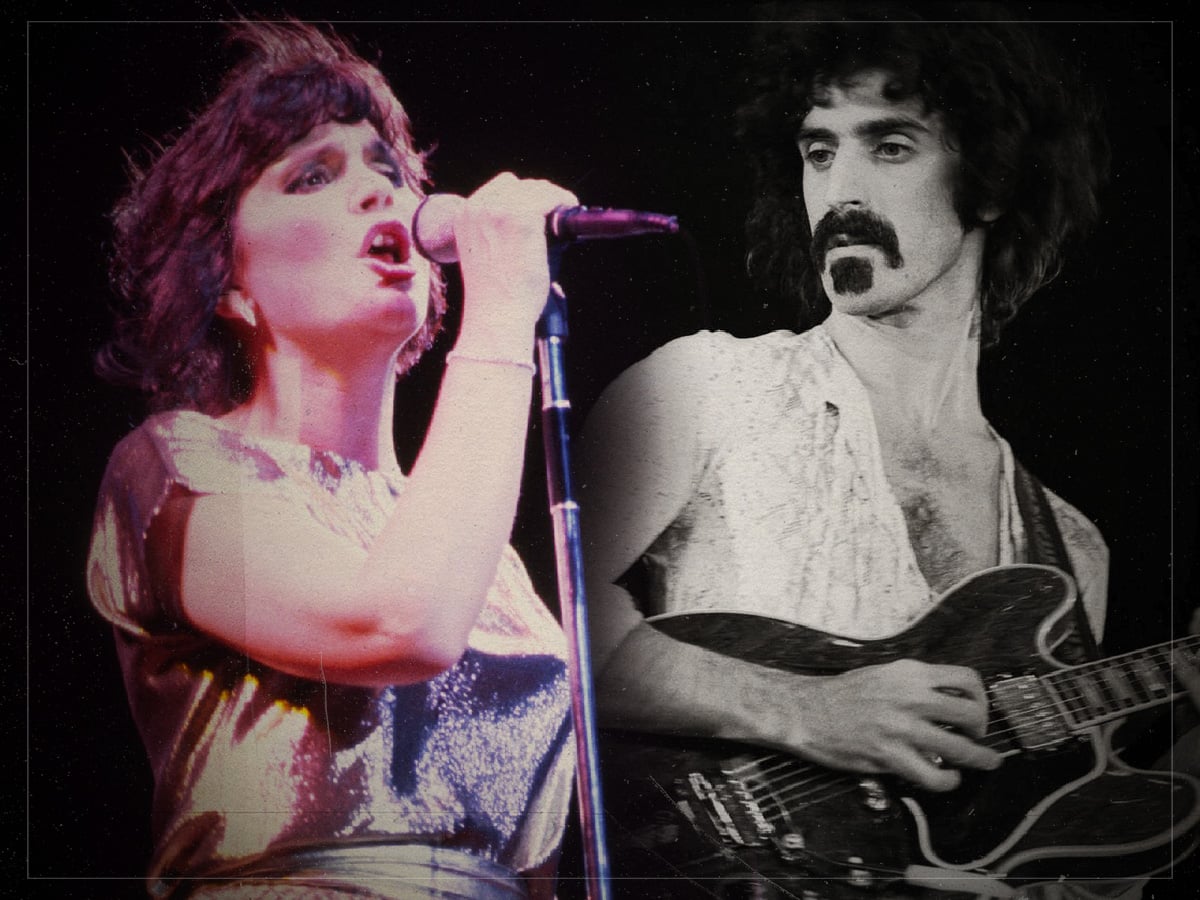

It’s common for a musician to struggle with the vulnerability of listening back to their own work. However, when someone like Linda Ronstadt declares their hatred for the one thing that gave her her name, it’s really something.

“I hate music,” Ronstadt once said, words that disregard everything that she’s ever said about those she grew up with and those she surrounded herself with at LA’s bustling Troubadour scene. When you dig deeper, it’s clear that isn’t exactly the case, but the words themselves seem cutting enough to make you think that Ronstadt might just despise everything to do with the art form and all that it’s given her.

In reality, however, it’s more to do with that vulnerability, and having to live with being her own worst critic whenever it comes to listening to her own voice. Ronstadt’s main gripe has always been that she feels she was never a good singer, or at least, not the kind that she wanted to be, until much later in her career. But by that point, most of her best work had already gone out.

As she once reflected, “I hate [all my records]. I don’t particularly care for the sound of my voice. I’m delighted when anybody likes it, and I always try my best. I generally feel a song when I’m singing it, but I just don’t like to hear it back.”

That said, there are some moments that Ronstadt likes, like her collaborations with Dolly Parton and Emmylou Harris, and those she did with arranger Nelson Riddle. She also enjoyed Adieu False Heart, the record she made with Ann Savoy, even though it was after she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, and she found it difficult to sing. “I had to whisper everything,” she told The Guardian. “But that was a really successful record for us – artistically successful.”

As someone who also said that singing was a major part of who she is, it’s easy to understand why Ronstadt missed being able to do it the way that she used to, especially the sense of community that it gave her or the way that it made her feel closer to her heritage and her upbringing. These simplicities, like harmonising with others, were what she missed doing the most, especially as she considers music to be the “core” of most of her relationships, and something she would do when people like Emmylou Harris called her up on the phone for a catch-up.

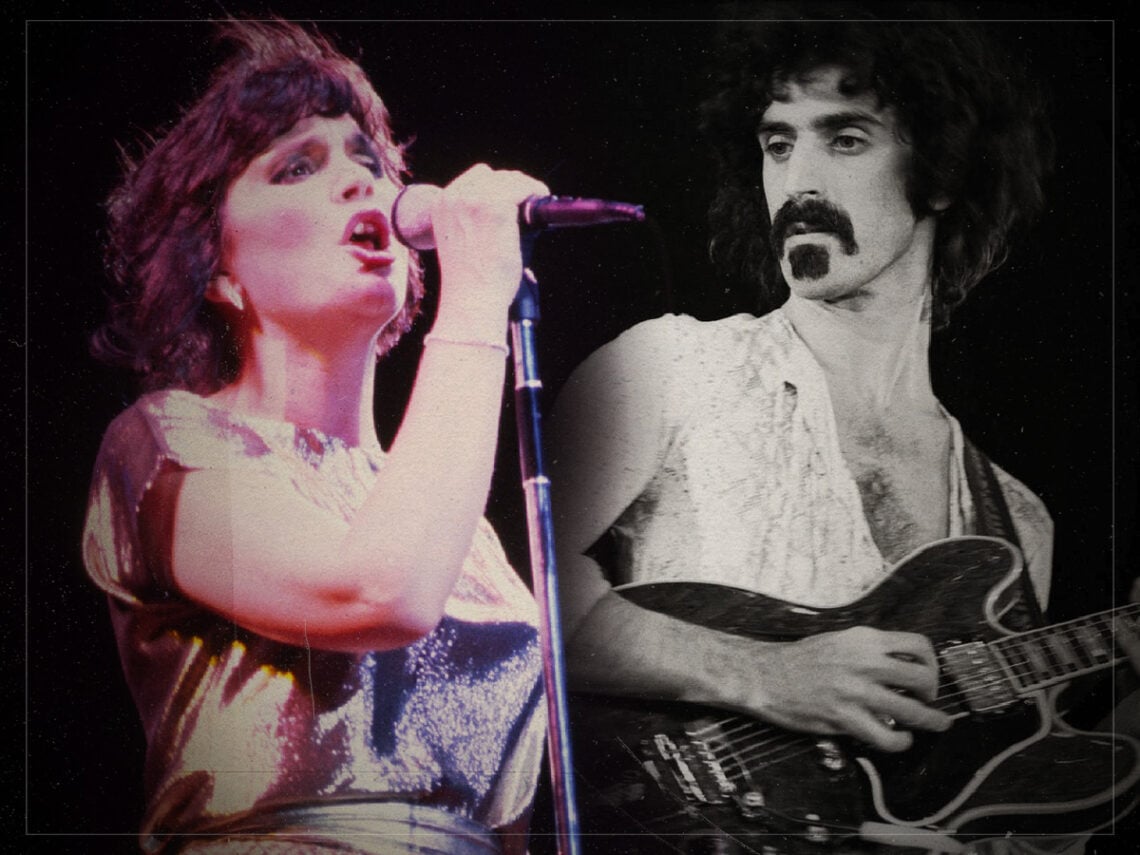

These simplicities are also likely the reason why some of her collaborations didn’t really make any sense. Aside from her inability to listen to herself, if she didn’t feel emotionally connected to something, she either didn’t do it or didn’t understand it to begin with. This was the case when it came to her duet with Frank Zappa for a radio jingle for an electric razor, something that Ronstadt later recognised was completely out of the blue.

“Frank wrote it. It was so musically complicated that I don’t know if they liked it,” she said. “It was kind of like Bambi and Deep Throat on the same bill; it was not a likely pairing.”

Most people agreed. Mainly, it seemed that both of them occupied such distinctive spaces that a collaboration wouldn’t have even been considered, let alone discussed. After all, Ronstadt’s appreciation for simple, emotive vocals and melodies attached to those she knew and loved growing up would never really be a match for Zappa’s focus on complex and meticulous innovation, no matter the triviality of the project itself.

Related Topics