Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

For millennia, supernovae were rare, once-per-century sights.

What appears to be a double-lobed nuclear explosion is actually the result of a rare astronomical outburst known as a supernova impostor: a precursor to a supernova, rather than the real thing. A “small” nuclear explosion occurred in the massive star Eta Carinae nearly 200 years ago, but the star continues to live on on the inside, with the two expanding lobes shown here resulting from the aftermath of that outburst.

Credit: NASA, ESA, N. Smith (University of Arizona, Tucson), and J. Morse (BoldlyGo Institute, New York)

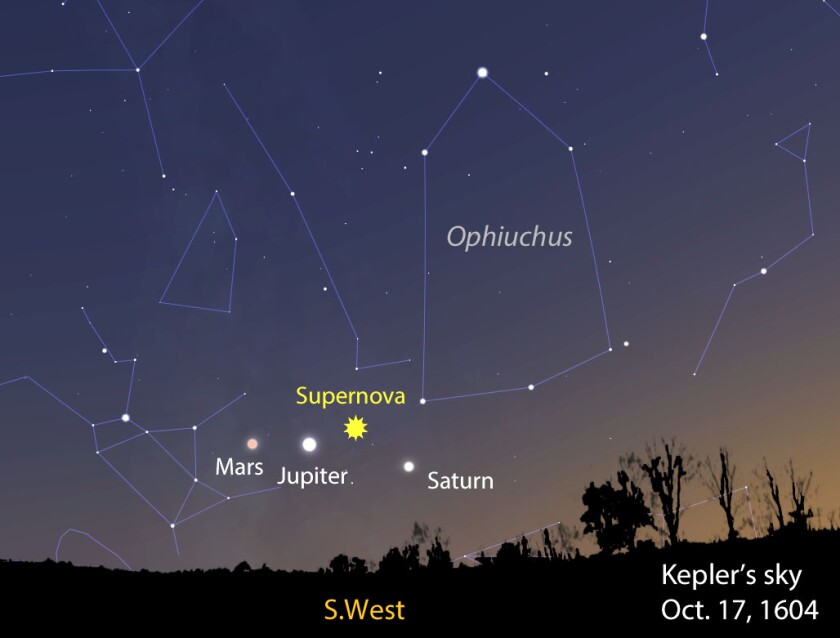

The last naked-eye Milky Way supernova occurred way back in 1604.

In 1604, a supernova appeared to skywatchers on Earth, between the constellations of Ophiuchus and Sagittarius. Known as Kepler’s supernova, on October 17, 1604, it made a brilliant “line” with Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn flanking it. It remains the Milky Way’s most recent naked-eye supernova, even today, more than 400 years later.

Credit: Sterllarium/InForum

But with modern astronomy, they’ve appeared all across the Universe.

As recently as 2019, there were only 19 published galaxies that contained distances as measured by Cepheid variable stars that also were observed to have type Ia supernovae occur in them. We now have distance measurements from individual stars in galaxies that also hosted at least one type Ia supernova in 42 events, 35 of which are independent galaxies with excellent Hubble imagery. Those 35 galaxies are shown here.

Credit: A.G. Riess et al., ApJ, 2022

Similarly, gravitational lenses abound, with mass bending and distorting space.

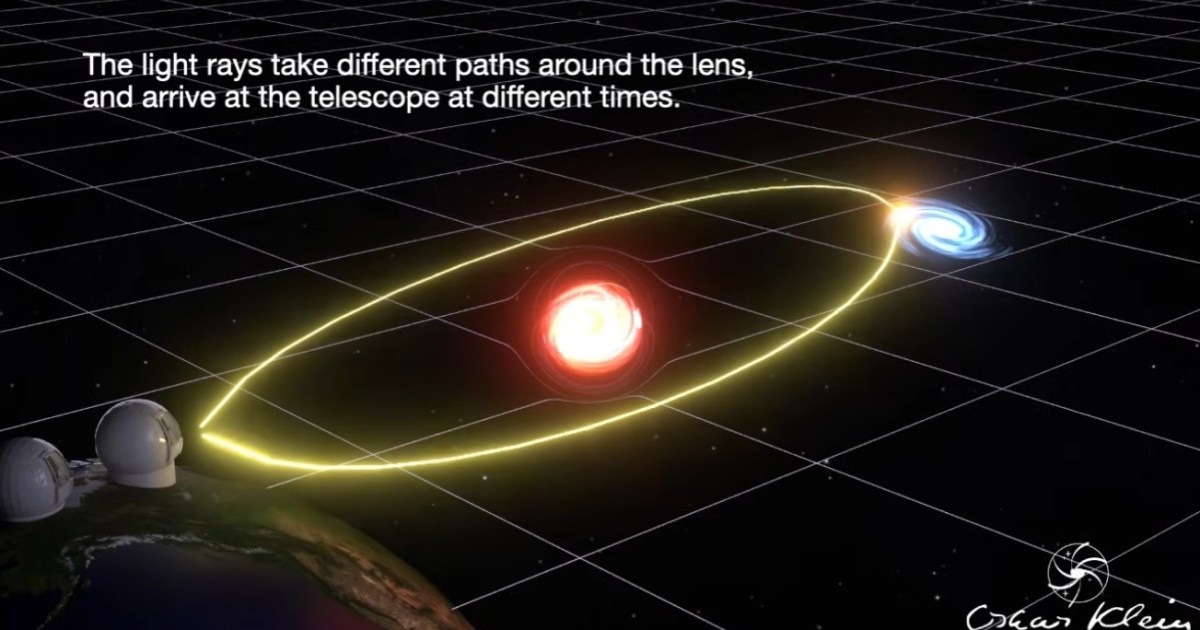

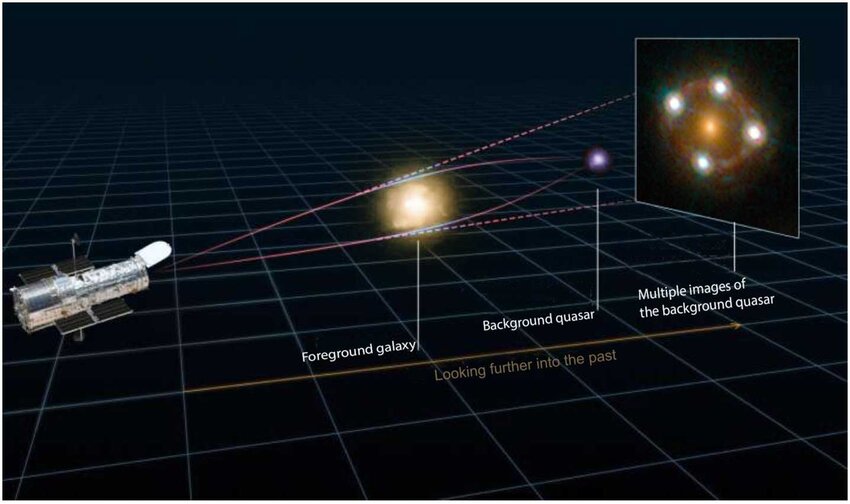

An illustration of gravitational lensing showcases how background galaxies — or any light path — are distorted by the presence of an intervening mass, but it also shows how space itself is bent and distorted by the presence of the foreground mass. When multiple background objects are aligned with the same foreground lens, multiple sets of multiple images can be seen by a properly-aligned observer, or even an “Einstein ring” in the case of perfect alignment. If a transient event, like a supernova, occurs in the background galaxy, it will appear with time delays in the various images.

Credit: NASA, ESA & L. Calçada

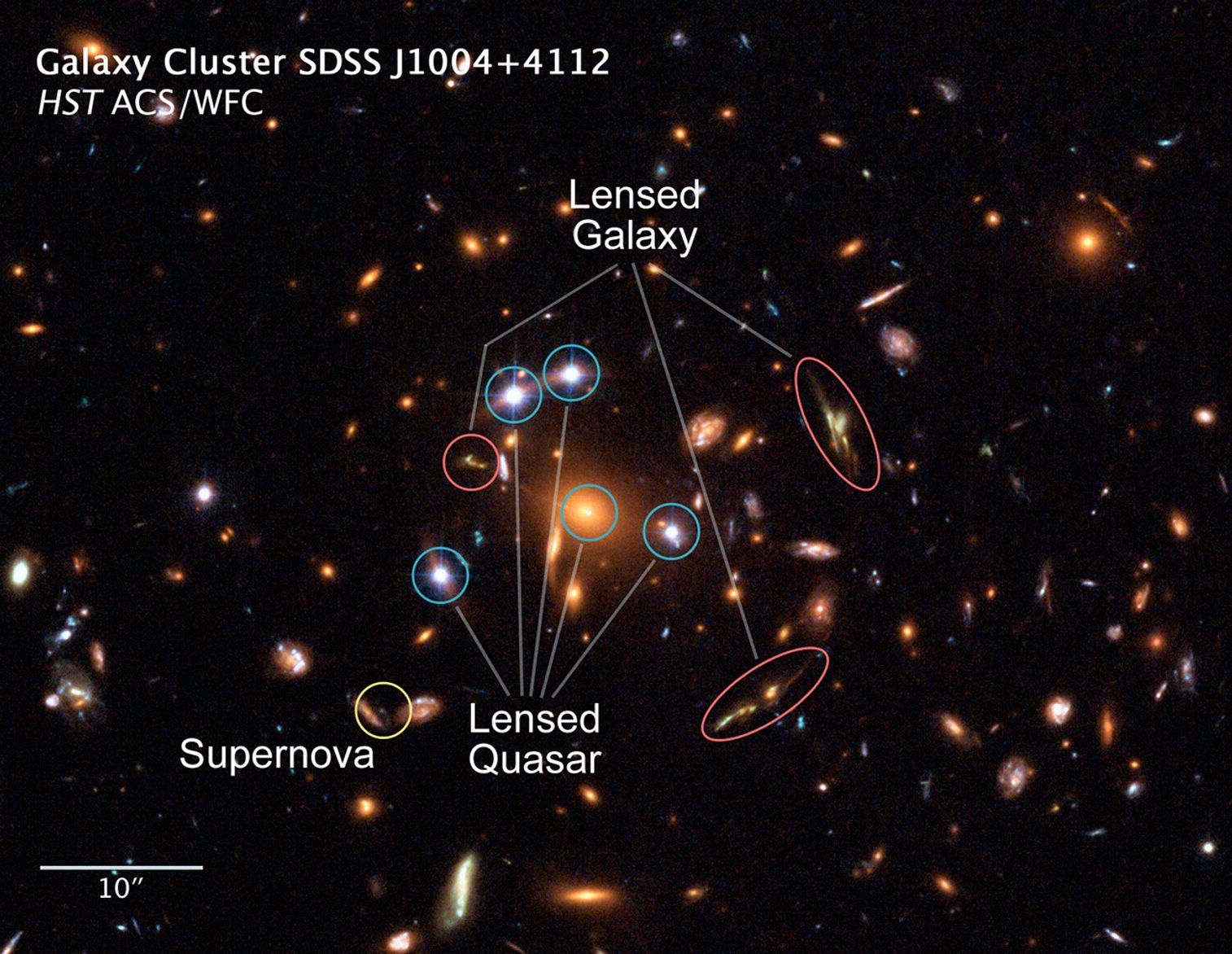

The light from background objects often appears multiple times.

This densely populated region of space is focused on galaxy cluster SDSS J1004+4112, and showcases several objects that appear multiply imaged owing to gravitational lensing. Once called a “five star” lens, the star-like appearances seen near the cluster’s center are actually the same quasar imaged five times in the same field-of-view: a deceptive trick of light and gravity.

Credit: ESA, NASA, K. Sharon (Tel Aviv University) and E. Ofek (Caltech)

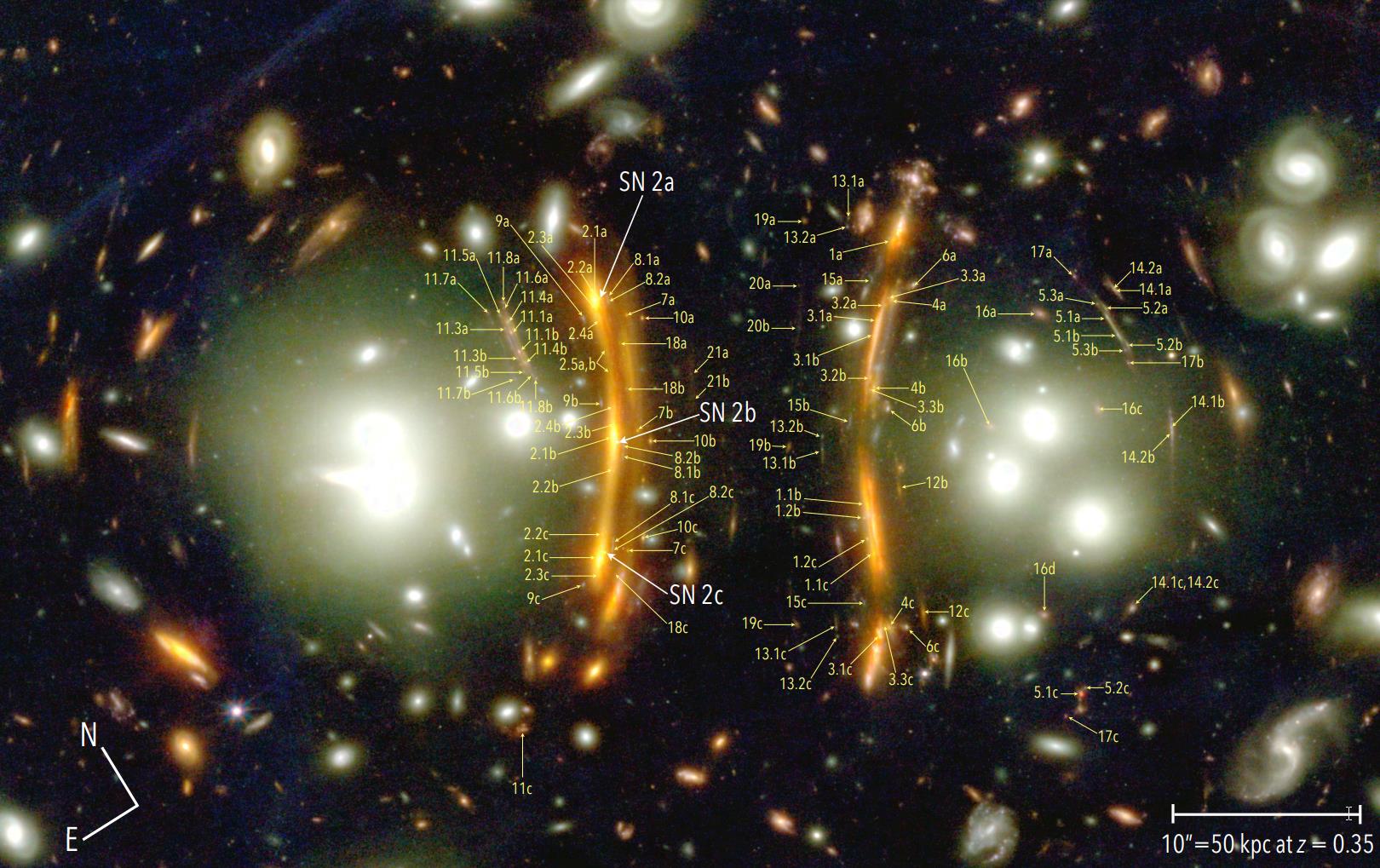

When galactic brightness varies — from quasars or supernovae — those multiple images vary, too.

This image shows not only the central dual cores of galaxy cluster G165, but also the labeled lensed features. All told, there are at least 21 independent multiply-imaged background light sources found in this field of view. The big orange arc at left, called “Arc 2,” contains the second-most distant type Ia supernova ever discovered, and it was seen by JWST on repeat in all three images, as annotated here.

Credit: B. Frye et al., ApJ submitted, 2023

Different images possess different path-lengths, causing delays in those features’ appearances.

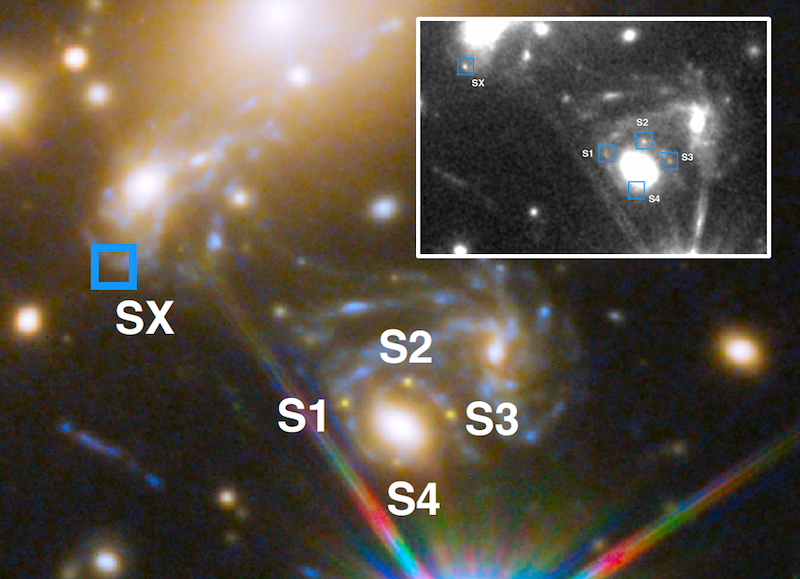

This Hubble telescope image shows the locations of the first four images (S1–S4) of a lensed supernova seen in late 2014. A full 376 days later, astronomers detected a fifth image at the point SX. By using the time-delay information and the stretching of the light inferred by the time it’s arrived at our eyes, we can estimate the cosmic expansion rate. As we collect greater numbers of multiply-lensed supernovae, this could become a key method for measuring the cosmic expansion rate.

Credit: P. L. Kelly et al., Science, 2023

Our first multiply lensed supernova exhibited significant delays across five separate images.

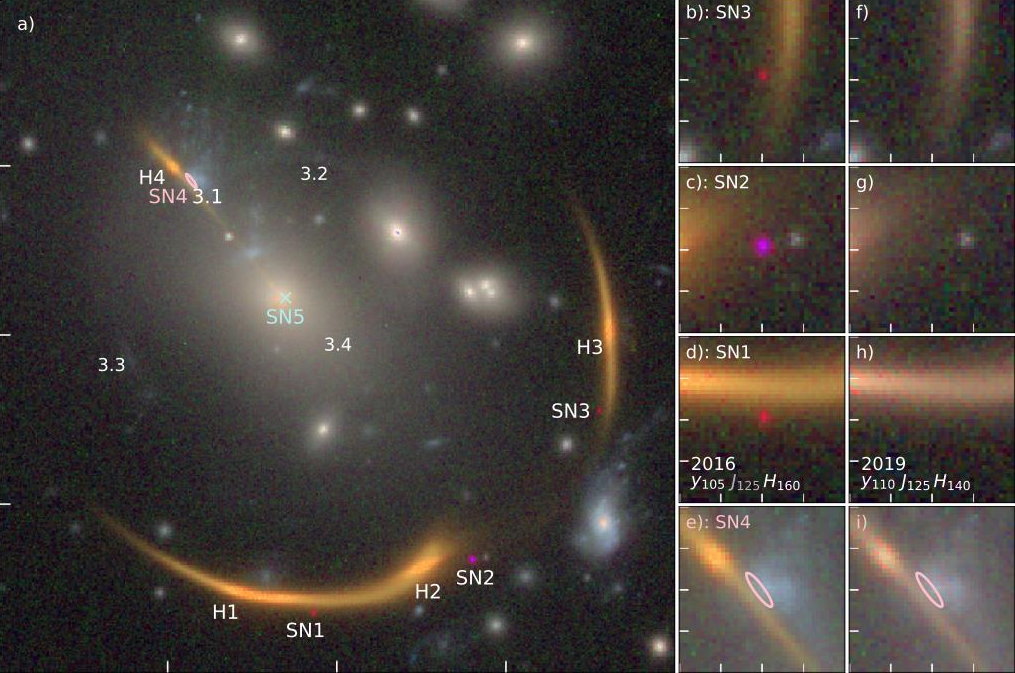

This series of images, captured with the Hubble Space Telescope, shows four images, stretched out into arcs by gravitational lensing, of the same galaxy. In 2016, we captured a supernova in one of these images (labeled SN1), and then saw a second and third separated by a total of around 6 months. Based on the reconstructed geometry of the lensing foreground cluster, we can expect to see the fourth replay in the location labeled SN4 in the year 2037.

(Credit: S.A. Rodney et al., Nature Astronomy, 2021)

These lensing path delays, wherever they occur, yield distance and redshift information.

This grid, showing 80 independent multiply-lensed and/or binary quasars, showcases the power of large surveys, like DESI here, for revealing large numbers of multiply-lensed quasar systems. Over 400 such candidate systems have been identified by DESI alone, with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory expected to far surpass that number.

Credit: C. Dawes et al., Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 2023

Multiply lensed, time-varying objects enable measurements of the cosmic expansion rate.

This illustration shows several different light-paths from the same object, the background quadruply-lensed quasar HE0435-1223. Because the light-paths are different lengths, the arrival time corresponding to quasar brightening or faintening episodes will differ across the multiple images. Measuring the time delays and reconstructing the lensing effect allows one to measure an absolute scale in the cosmos, leading to a measurement of the expansion rate.

Credit: Martin Millon, Wong et al., MNRAS, 2017

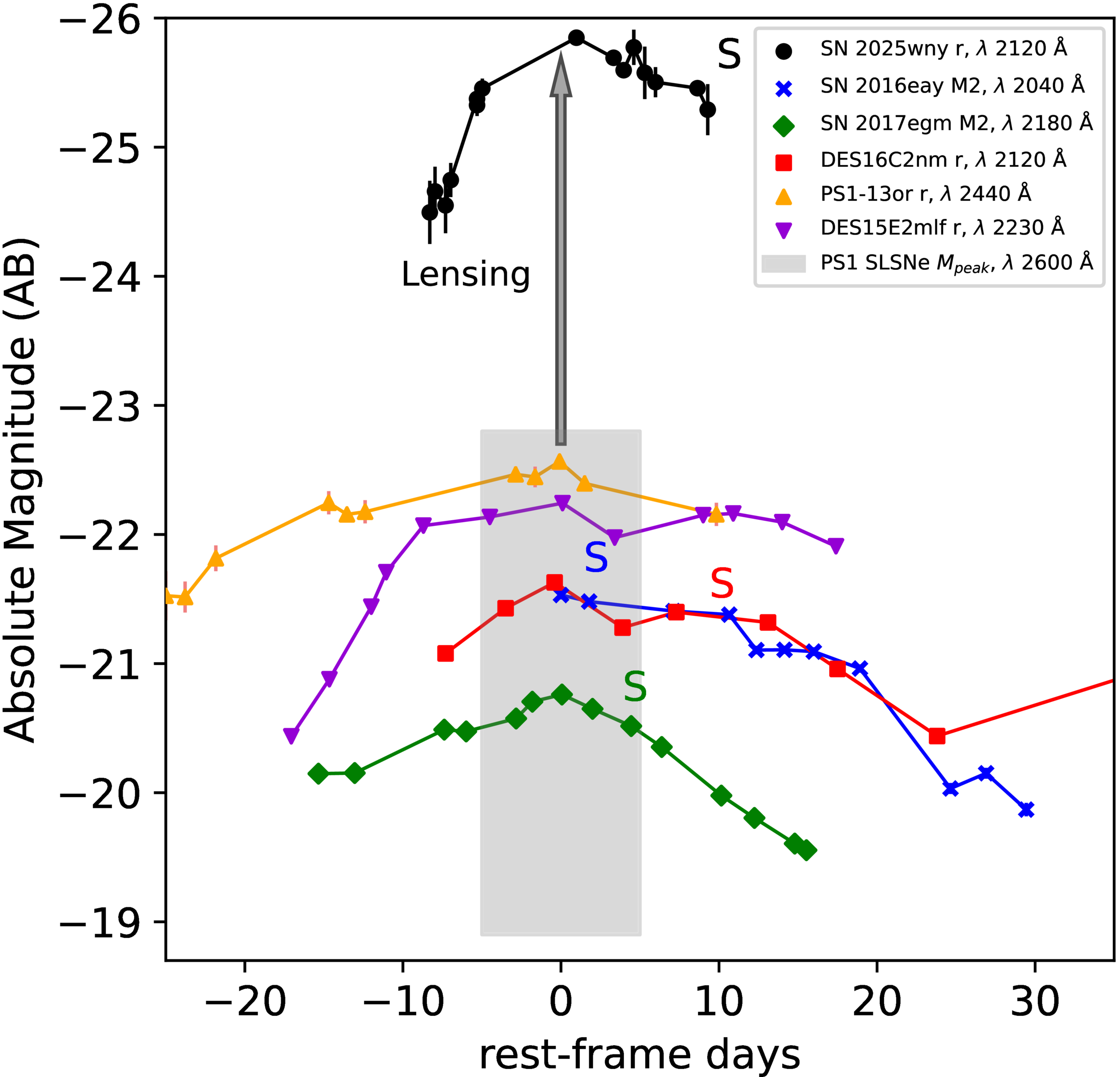

In 2025, supernova SN 2025wny became humanity’s first multiply imaged superluminous supernova.

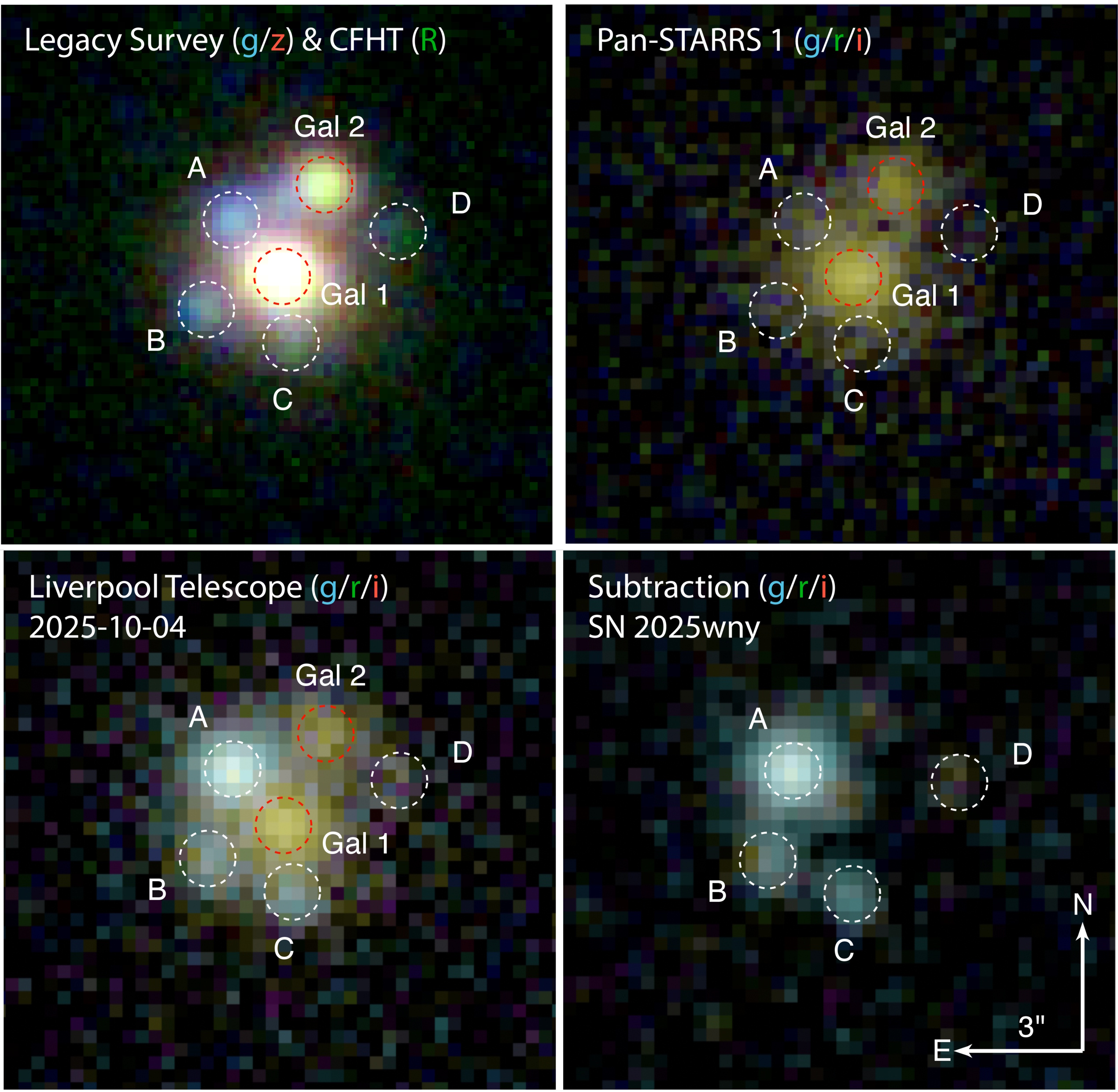

This four-panel image shows ground-based imaging of the system containing the superluminous supernova SN 2025wny. The white-circled regions labeled A through D are the multiple images of the lensed supernovae, while the red circled regions are the two galaxies participating in the foreground lens. The lower-right panel shows the four images of the lensed supernovae after foreground subtraction.

Credit: J. Johansson et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

First identified with the Zwicky Transient Facility, follow-up ground based imaging revealed its nature.

This observations demonstrate that existing ground-based facilities are sufficient for time-delay cosmography.

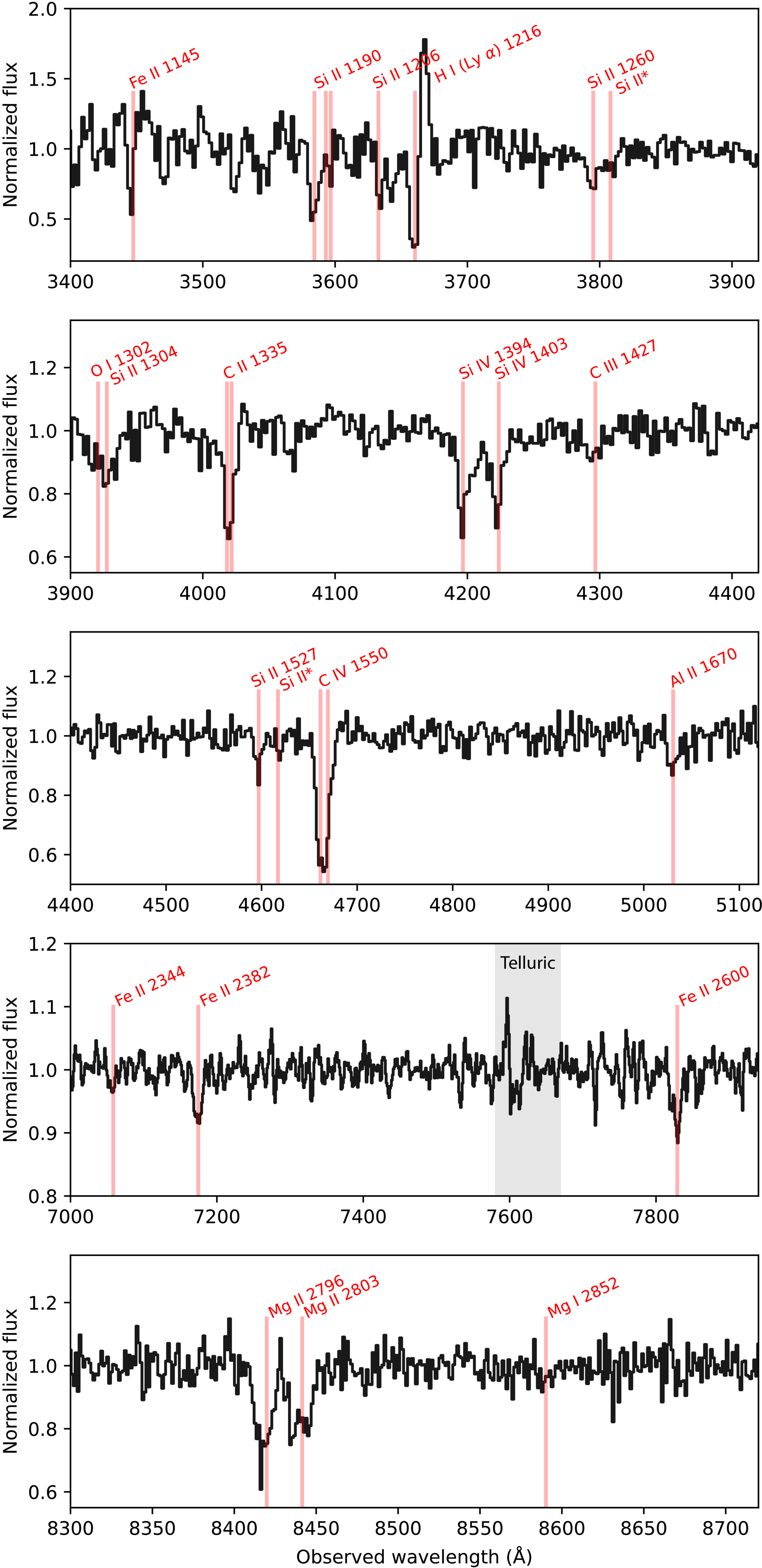

This spectrum shows the ground-based follow-up of the observations of the multiply-lensed superluminous supernova SN 2025wny, where many different elements in varying states of ionization have been detected. These observations enable astronomers to pin down the distance to, and redshift of, the distant galaxy hosting the lensed supernova.

Credit: J. Johansson et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

Absorption lines, magnification information, and light-curve features are all easily revealed.

This image, taken in April of 2025, shows the completed and operational Vera C. Rubin Observatory with its dome open during its First Look observation activities. Overhead, the Beehive Cluster (Messier 41) shines bright, while below, the glow of nearby small cities shines in this mountainous landscape.

Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA/P. Horálek (Institute of Physics in Opava)

With the advent of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, ~20 billion galaxies are continuously imaged.

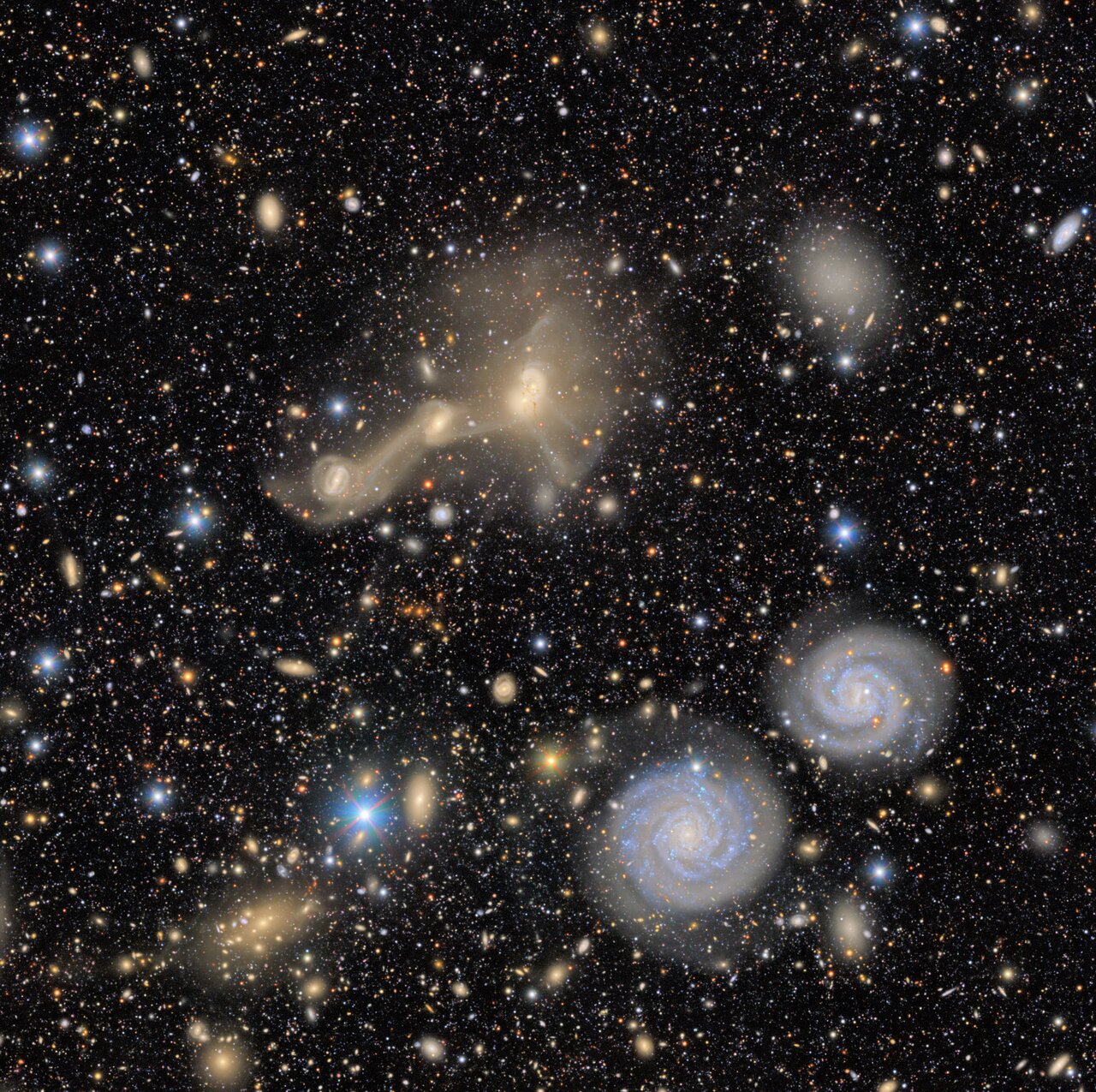

This image from the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s first look observations shows the galaxy pair NGC 4411, at lower right, which are far apart in 3D space and not interacting, along with the galaxies of RSCG 55, higher in the image, which are interacting. Rapidly and deeply imaging the sky, including regions like this, allow astronomers to search for small variations in brightness, leading to discoveries of quasars, supernovae, and other brightening/faintening phenomena.

Credit: RubinObs/NOIRLab/SLAC/NSF/DOE/AURA

Many are lensed, yielding expectations of thousands of multiply lensed supernovae by 2035.

The observed faintness of the distant lensed supernova SN 2025wny is no match for the Vera C. Rubin’s ultra-sensitive camera, which is capable of reaching astronomical magnitudes of +24.5 in a single image and of +27.8 magnitudes with a full stack of images summed together. This represents an improvement of orders of magnitude over existing transient facilities such as ZTF, with faster cadence (shorter time between images) expected to reveal even more transient events.

Credit: J. Johansson et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2025

This unprecedented sensitivity advances our cosmic understanding: one lensed system and one transient/supernova at a time.

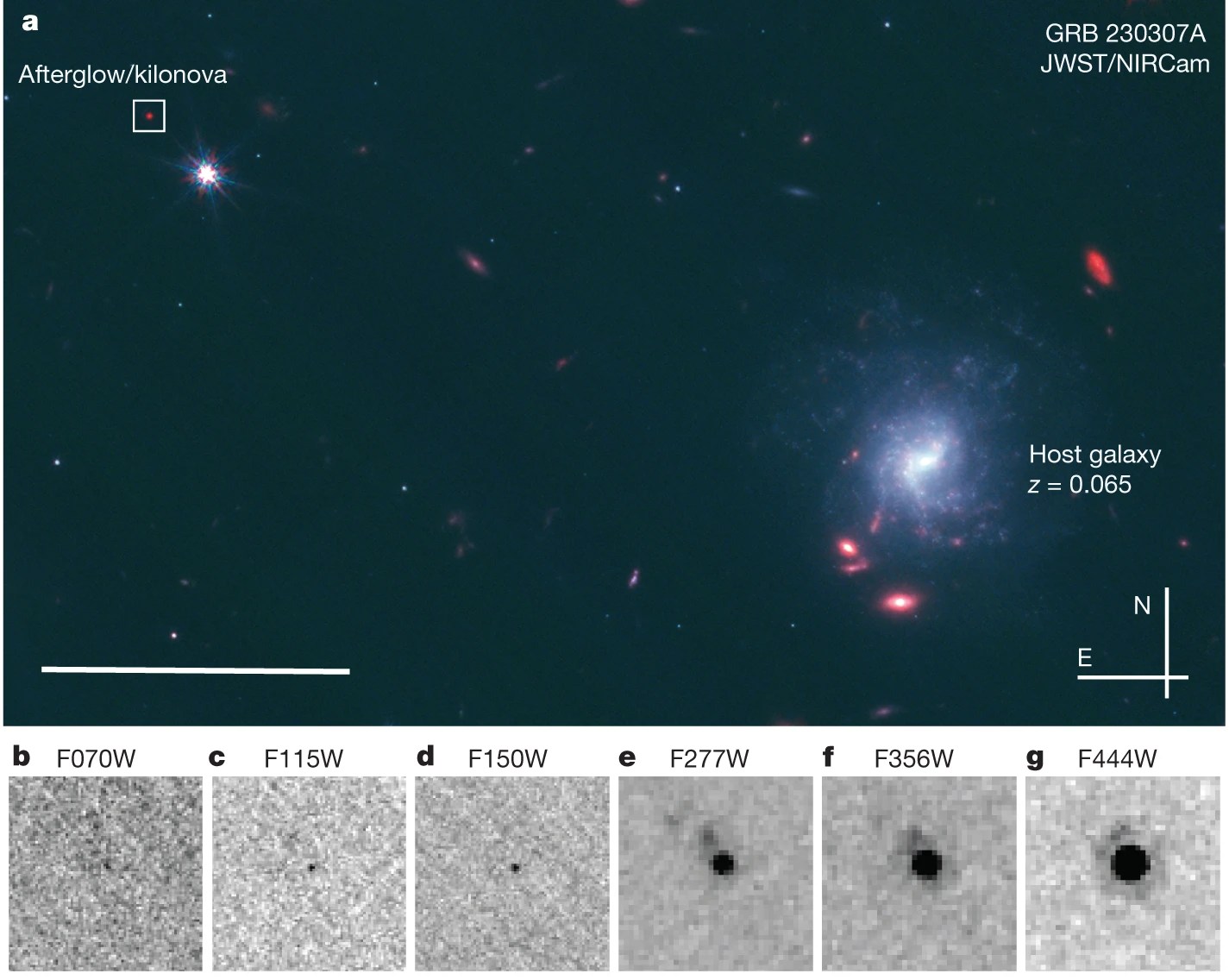

This image shows a photometric JWST image of a host galaxy for a neutron star-neutron star merger, along with the location of the remnant of GRB 230307A, shown at the top left. The source is faint and barely detectable at bluer (shorter-wavelength) colors, but appears bright farther into the infrared. Many other transient events, including tidal disruption events, supernovae, and novae will be discovered by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, enabling follow-ups with telescopes like JWST.

Credit: A.J. Levan et al., Nature, 2023

Mostly Mute Monday tells an astronomical story in images, visuals, and no more than 200 words.

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.