In one of the most fascinating globular clusters in the Milky Way, Omega Centauri, astronomers have long suspected the presence of a massive black hole at its core. A recent study, published on ArXiv, used cutting-edge radio telescopes to confirm or deny the existence of this black hole. However, despite intensive efforts, the results were unexpected—no detectable emissions were found, challenging our understanding of how such black holes behave in star-deprived environments.

A Dark Mystery in the Heart of Omega Centauri

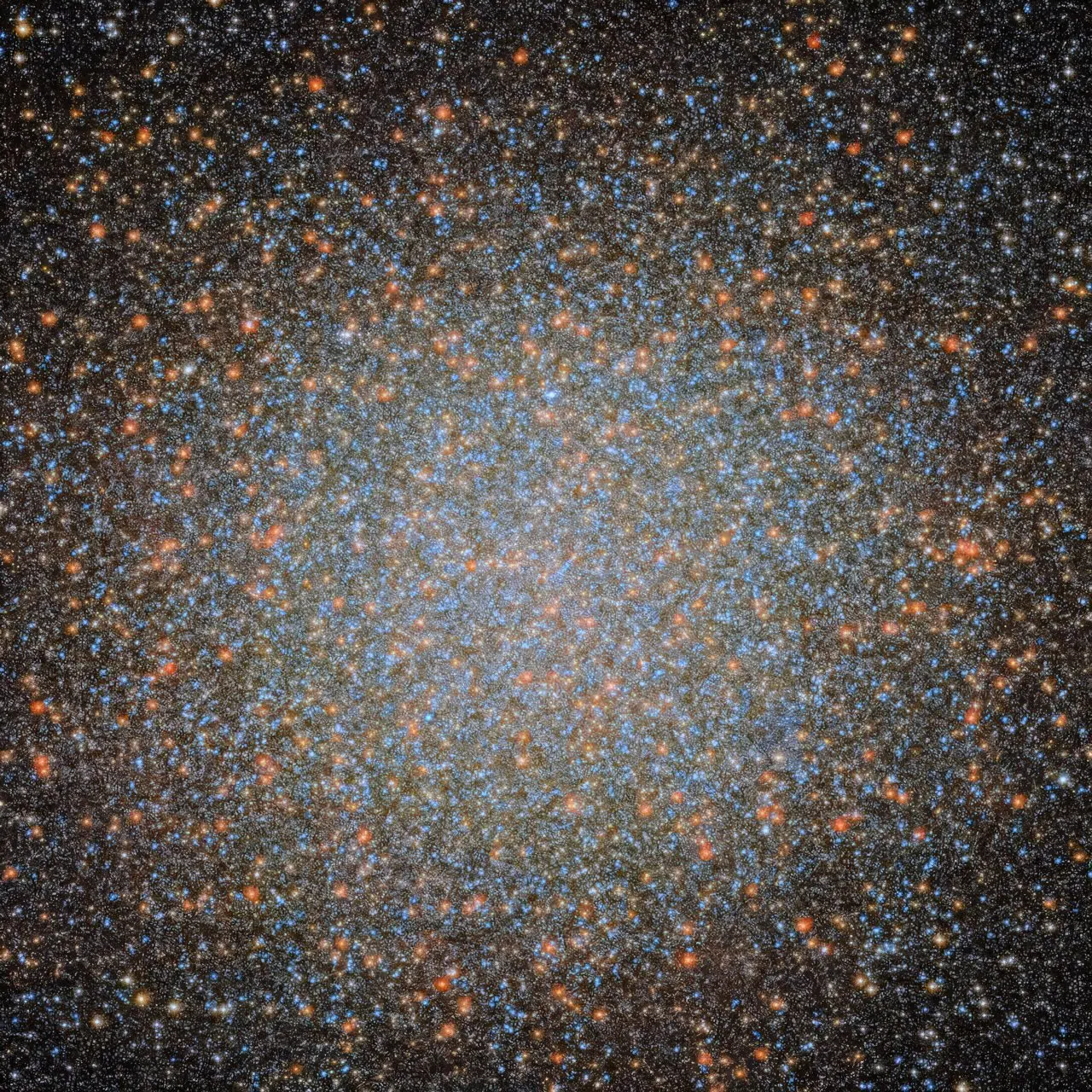

Omega Centauri, the largest and brightest globular cluster in the Milky Way, has captured the imaginations of astronomers for decades. Located about 15,000 light-years away from Earth, this dense sphere is home to around 10 million stars. The cluster’s central region, however, is where things get intriguing. Earlier observations, notably using the Hubble Space Telescope, uncovered a strange phenomenon: seven stars in the cluster’s core were moving far too quickly to remain bound unless an unseen massive object—likely a black hole—was holding them in place.

These findings suggested that an intermediate-mass black hole, with a mass between 8,200 and 47,000 times that of the Sun, could be lurking at Omega Centauri’s core. Such black holes, which sit between stellar-mass black holes and supermassive black holes, remain elusive in the study of black holes. While stellar-mass black holes form from collapsing stars and supermassive black holes dominate the centers of galaxies, the intermediate-mass black holes represent a mysterious “missing link” in our understanding of black hole evolution.

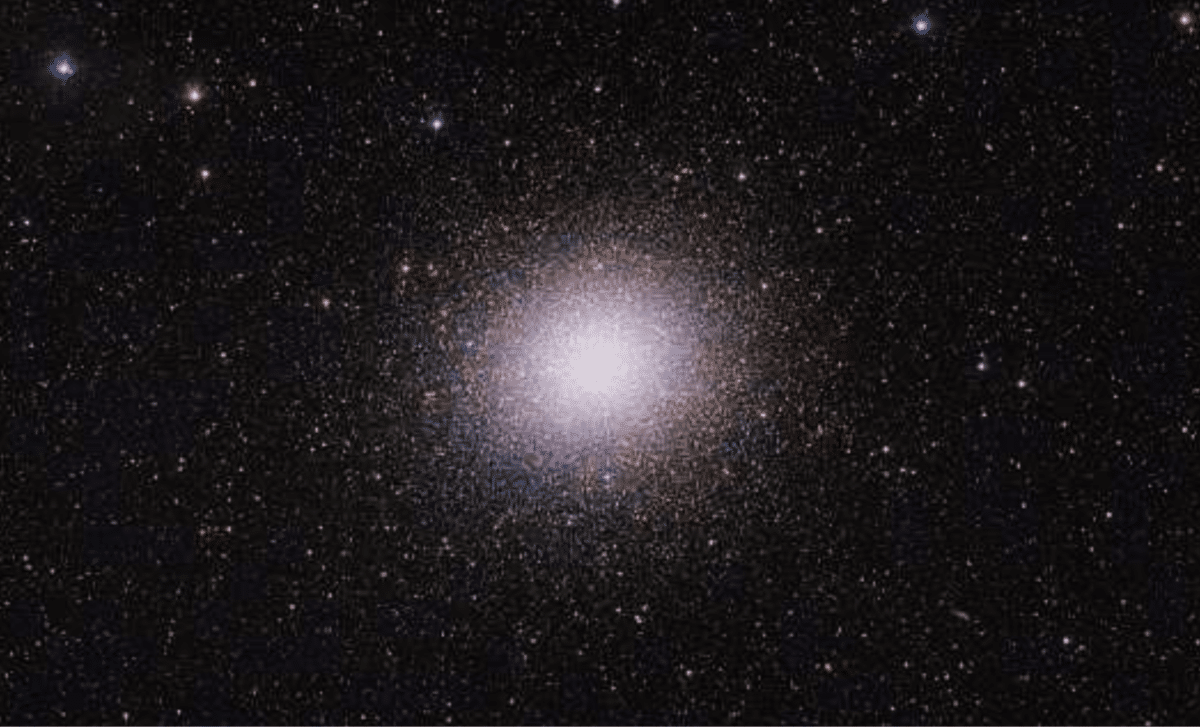

Omega Centauri. Credit: NASA

Omega Centauri. Credit: NASA

The Radio Search and What Wasn’t Found

To further explore this intriguing possibility, a team of researchers led by Angiraben Mahida turned to radio astronomy. Their goal was to search for the black hole’s accretion signature—something that occurs when a black hole pulls in gas and dust, creating a hot accretion disk that emits across the electromagnetic spectrum, including radio waves. Using the Australia Telescope Compact Array, the team spent approximately 170 hours observing the heart of Omega Centauri.

The results were surprising. Despite the sensitivity of the observations, which reached an impressive 1.1 microjanskys at 7.25 gigahertz—the most sensitive radio image ever obtained of the cluster—the team found no trace of radio emissions. No sign of an accretion disk appeared at any of the proposed cluster centers where the black hole should reside. The absence of such emissions led the researchers to conclude that if a black hole is indeed present, it must have a significantly low accretion efficiency, with the upper limit being less than 0.004—far lower than expected.

The findings are detailed in a study published on ArXiv, adding a new layer of complexity to the ongoing search for intermediate-mass black holes.

A Quiet Black Hole: Why the Silence?

The non-detection of radio emissions raises important questions about the nature of black holes in environments like Omega Centauri. The researchers speculated that this silence might be due to the cluster’s unique history. Omega Centauri is believed to be the stripped core of a dwarf galaxy that was absorbed by the Milky Way billions of years ago. As a result, the region around the central black hole might simply be starved of the necessary gas and dust that would feed an accretion disk.

Unlike supermassive black holes at the centers of active galaxies, which are surrounded by vast amounts of gas that fuel intense emissions, the black hole in Omega Centauri might exist in a “desert” of gas, preventing it from feeding in the usual way. Without the material needed for accretion, the black hole would be nearly invisible across the electromagnetic spectrum. In essence, it’s a quiet black hole, operating in a region devoid of the fuel required for its typical radiation.