Astronomers have been treated to a stunning fireworks display from around a young star called Fomalhaut. The events, detected in 2004 and 2023, represent the first collisions between large objects seen in a planetary system beyond our own. Observing collisions occurring in a young star system like that of Fomalhaut could provide astronomers with a window to the conditions under which our own planet and its siblings formed around the infant sun around 4.6 billion years ago.

You may like

Illustration of the collision of two planetesimals in the circumstellar disc of the star Fomalhaut. (Image credit: Thomas Müller (MPIA))

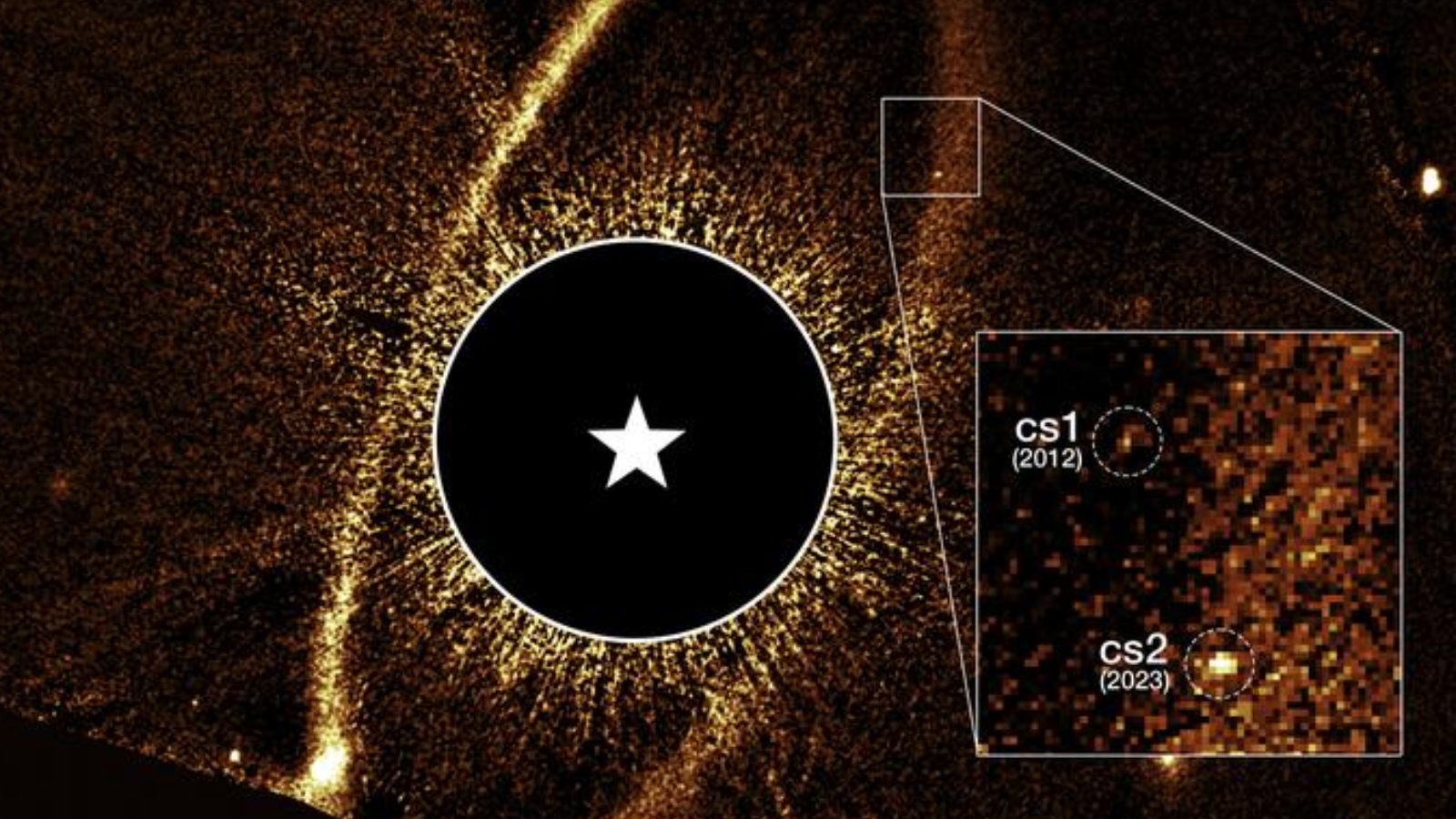

Kalas added that the team did not directly see the two objects that crashed into each other, instead spotting the aftermath of this enormous impact.

He and his colleagues first began investigating the young star Fomalhaut back in 1993, hunting for the debris leftover from planet birth, eventually finding a disk of this material around the star with the Hubble Space Telescope. Then, in 2008, Kalas found a bright spot in that so-called protoplanetary disk that was initially thought to be a planet. This new research suggests that this planet, Fomalhaut b, is actually a dust cloud that was stirred up by the collision between planetesimals in the protoplanetary disk.

“This is a new phenomenon, a point source that appears in a planetary system and then over 10 years or more slowly disappears,” Kalas said. “It’s masquerading as a planet because planets also look like tiny dots orbiting nearby stars.”

The brightness of the events observed in 2004 and 2023 revealed that the bodies involved were around 37 miles wide (60 kilometers) or more, meaning they are each at least four times as large as the Chicxulub impactor, the asteroid that struck Earth 66 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs along with 75% of all species of animals and plants.

Hubble Space Telescope image shows the debris ring and dust clouds cs1 and cs2 around the star Fomalhaut. (Image credit: NASA, ESA, Paul Kalas/UC Berkeley. Image Processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI))

“The Fomalhaut system is a natural laboratory to probe how planetesimals behave when undergoing collisions, which in turn tells us about what they are made of and how they formed,” team member Mark Wyatt, of the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, said. “The exciting aspect of this observation is that it allows us to estimate both the size of the colliding bodies and how many of them there are in the disk, information which is almost impossible to get by any other means.” Indeed, the team estimates that there are around 300 million planetesimals in the region around Fomalhaut of sizes similar to those involved in these two crashes. The fact that carbon monoxide gas has previously been detected in this system indicates these objects are rich in volatiles, substances such as hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen and methane that easily turn gaseous at low temperatures.

That makes these icy bodies in Fomalhaut similar to the frigid comets of the solar system, which are also packed with volatiles. In a further comparison with the solar system, Kalas suggested that the 2004 and 2023 dust clouds seen by the team are akin to the dust cloud created in 2022 when NASA struck the moonlet Dimorphos with the DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) to test if this could shift its parent asteroid Didemos.

Kalas and colleagues will continue to investigate Fomalhaut with Hubble, also adding the powerful infrared vision of the James Webb Space Telescope to their investigation. This should allow them to track how the cloud seen in 2023 evolves. It is already around 30% brighter than the 2003 cloud, and observations conducted in August 2025 confirmed that it is indeed still visible.

As this investigation continues, Kalas warns astronomers not to fall into the trap of mistaking dust clouds for newly formed planets around infant stars.

“These collisions that produce dust clouds happen in every planetary system,” Kalas said. “Once we start probing stars with sensitive future telescopes such as the Habitable Worlds Observatory, which aims to directly image an Earth-like exoplanet, we have to be cautious because these faint points of light orbiting a star may not be planets.”

The team’s research was published on Thursday (Dec. 18) in the journal Science.