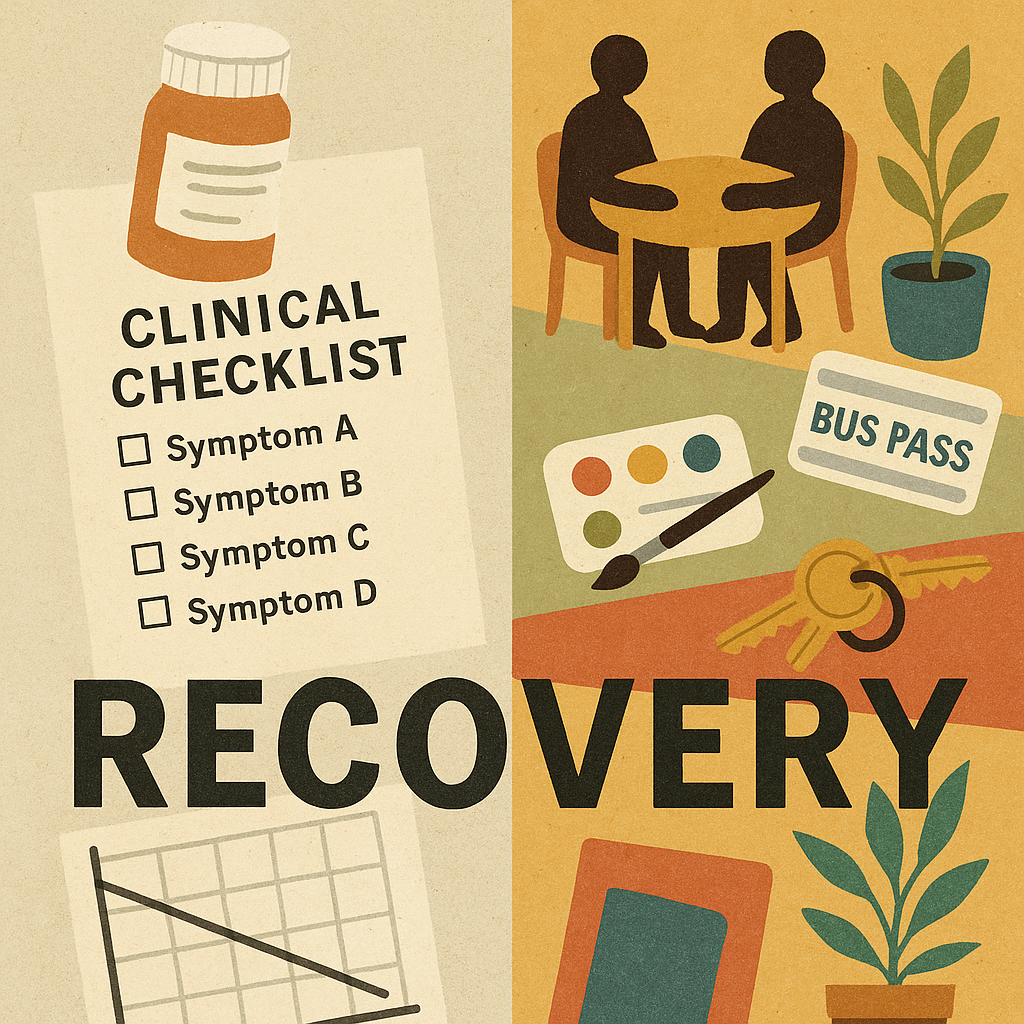

In their new chapter Reconsidering ‘Recovery,” Larry Davidson and Kim Jørgensen call for a paradigm shift toward personal recovery, emphasizing the pursuit of a meaningful, connected, and empowered life even in the presence of ongoing mental health challenges.

They respond to the persistent difficulty within mental health systems and local communities to define recovery, and the implications this ambiguity has for policy and practice.

As the opening chapter of The Path to Mental Health Recovery, the piece critically examines the evolution of the concept of recovery, situating it within both historical and contemporary frameworks. Through an integrative analysis of case-based reflections and historical perspectives, Davidson and Jørgensen demonstrate the impact and potential of changing definitions of recovery.

Approaching their work through a disability lens, the authors emphasize the value of person-centered care, peer support, and community-based participation.

The authors write:

“Real change requires systemic reforms, including policies that prioritize recovery-oriented care, funding for community-based support, and the integration of lived experience into decision-making. Training programs must equip professionals with a broader understanding of mental health beyond diagnosis and medication, while regulatory frameworks should move away from a narrow focus on symptom management. Without these deeper structural changes, education alone risks being a surface-level intervention that fails to challenge the entrenched systems shaping mental health services today.”

Davidson, a longtime recovery researcher at Yale, has helped shape recovery-oriented practice in the U.S. and internationally. Jørgensen, a Danish scholar whose work focuses on recovery-oriented practice and user perspectives across health systems, brings a European lens and a strong interest in how power works in “helping” institutions. They argue that the field has too often treated recovery as a clinical endpoint defined by fewer symptoms, fewer hospitalizations, and better scores on standardized measures. They call for a more ambitious definition, one rooted in disability studies, civil rights, and the knowledge produced by people who have lived through psychiatric systems.

The chapter is framed throughout by a clinical vignette depicting an encounter between a psychiatrist and a service user with depression. Rather than centering the interaction on symptom reduction, the psychiatrist supports the service user in identifying meaningful goals and aspirations, such as art and relationships, to cultivate hope, identity, and well-being. The vignette illustrates what can be possible when providers depart from traditional or dominant approaches to recovery and instead recognize individuals’ capacity to lead fulfilling lives, all while still experiencing ongoing mental health challenges.

Davidson and Jørgensen contextualize this approach through a historical analysis that challenges prevailing assumptions about recovery, emphasizing the dynamic nature of psychiatric thought through time. They demonstrate that the evolution of the concept of recovery was not a linear progression toward more compassionate care. In the late 18th century, Philippe Pinel advanced a more optimistic view, advocating for the dignity and respect of individuals experiencing severe mental illness and emphasizing their capacity for recovery.

This perspective shifted dramatically in the 20th century. Influenced by Kraepelin and institutionalized through diagnostic classification systems such as the DSM and ICD, psychiatry adopted a more pessimistic and reductionist framework. Conditions such as schizophrenia came to be framed as chronic, degenerative, and irreversible, profoundly shaping clinical practice, policy, and public perception through the dominance of the biomedical model.

The authors carefully examine the distinction between clinical recovery and personal recovery. Clinical recovery prioritizes symptom elimination and diagnostic outcomes. In contrast, the authors define personal recovery:

“Personal recovery is about reconnecting with who you are, setting meaningful goals, and building hope for the future. It’s not just about reducing symptoms, it’s about living a fulfilling life, even in the presence of ongoing challenges. Achieving this requires understanding and engaging with the social contexts and networks that shape daily life, as these can either support or hinder recovery. By shifting the focus beyond psychiatric institutions to strengths, hope, and inclusion, we can create meaningful pathways for recovery.”

Personal recovery is not framed as an end goal but rather as an ongoing process that entails navigating or transcending limitations or challenges.

To demonstrate how personal recovery can be supported and implemented in practice, Davidson and Jørgensen draw on the CHIME framework. CHIME identifies five interconnected dimensions of personal recovery: connectedness, hope, identity, meaning, and empowerment, which depend on relationships, social inclusion, and material conditions. The framework emphasizes the relational nature of recovery, and that empowerment emerges through participation and belonging.

They advocate for approaching recovery through a disability lens, stating:

“Acknowledging severe mental illness through a disability model is crucial for identifying opportunities and resources, ensuring that individuals with mental conditions can access and participate in society without hindrance. The imperative for community inclusion as a prerequisite for recovery, rather than a reward for overcoming mental illness, challenges the prevailing narrative. Stigma and discrimination present formidable barriers to community participation for individuals with mental illness, perpetuating negative perceptions and hindering self-identity as capable individuals.”

Additionally, the authors highlight a range of interventions and movements that demonstrate progress and possibility within a disability- and person-centered framework, many of which have emerged from service user and survivor movements. For example, Hearing Voices Groups, peer support workers, and recognizing lived experience as legitimate knowledge, as well as the Housing First initiative and Individual Placement and Support.

By integrating clinical and personal recovery, the authors argue that mental health services can move toward a more holistic and humane model of care. The chapter concludes that actual recovery-oriented practice requires not only reform within mental health systems, but a collective commitment to inclusion, dignity, and shared responsibility, redefining what and who mental health care is for.

In conclusion, Davidson and Jørgensen call for a transformation of psychiatric and mental health systems, moving away from authoritative, practitioner-driven decision-making toward collaborative environments in which individuals with diverse mental health experiences are recognized as partners in recovery.

“Despite facing numerous challenges, individuals with mental health conditions offer unique and critical perspectives on the effects of their conditions on their lives, including the effectiveness of different interventions… Ultimately, it is the individual with a mental illness who bears the primary consequences, both positive and negative, of decisions concerning their well-being and lifestyle. Consequently, the focal points of the Recovery movement center on person-centered planning and the active participation of individuals in the process. This approach, encapsulated in identifying and leveraging a person’s strengths, opportunities, and community resources, fosters hope and supports their pursuit of aspirations.”

Davidson and Jørgensen argue that “recovery” cannot be reduced to symptom control without betraying the very people the recovery movement emerged to serve. Their chapter presses mental health systems toward a rights-based, disability-informed model in which belonging and participation are not rewards for getting better, but prerequisites for living.

****

Davidson, L., & Jørgensen, K. (2025). Reconsidering “Recovery.” In K. Jørgensen, The Path to Mental Health Recovery (1st ed., pp. 1–16). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003489030-1 (Link)