The list includes the mastermind of Bilbao’s titanium-clad Guggenheim, Frank Gehry; the designer of the Eden Project, Nicholas Grimshaw; and Terry Farrell, the Postmodern protagonist behind MI6’s headquarters in London.

‘Starchitects’ aside, the past 12 months also saw the passing of former RIBA president David Rock, Poundbury architect Léon Krier, and writer and educationalist Alan Berman, among others.

As 2025 comes to a close, the AJ remembers the architects, educators and architectural historians we lost.

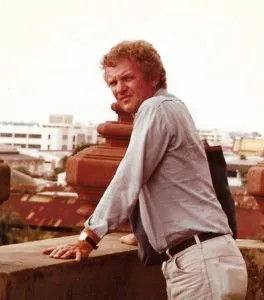

Frank Gehry

Photo: Alexandra Cabri

The Deconstructivism pioneering, Pritzker Prize-winning Canadian-American architect Frank Gehry died this month, aged 96.

Gehry’s titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum (1997) in Spain gave birth to the phrase the ‘Bilbao Effect’ – a term used around the world to describe how a single landmark scheme could act as a catalyst for successful regeneration.

In the UK, Gehry is best known in the UK for his Battersea Power Station housing in London, featuring rippled white facades; his Deconstructivist timber-tented Serpentine Pavilion; and his Maggie’s Centre in Dundee, Scotland, which The Twentieth Century Society described as ‘bothy-like’ and an ‘instant classic [which] helped introduce the fledgling [Maggie’s] programme to an international audience’.

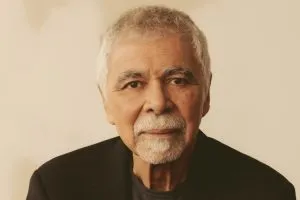

Robert AM Stern

Photo: RAMSA

US architect and academic Robert AM Stern died in November, aged 86.

Born in 1939, he went on to found RAMSA in the 1960s. The prolific architect led the design of iconic skyscrapers such as 15 Central Park West in Manhattan and the 58-storey Comcast Center in Philadelphia.

In the 1970s and early ’80s, he developed a reputation as a Postmodern architect, integrating Classical elements into his schemes.

His significant portfolio also includes the George W Bush Presidential Center in Dallas, the 45,000m² Tour Carpe Diem just outside Paris, Schwarzman College in Beijing and luxury homes across the USA.

Stern’s only foray into the UK, a seven-storey apartment block in Mayfair, London, is nearing completion.

David Rock

Former RIBA president David Rock died in November at the age of 96.

Rock studied at the Newcastle University School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape, then part of Durham University, leaving in 1952 with first-class honours.

From there, he joined Basil Spence’s legendary post-war architectural practice, where he spent five years. In the 1960s, Rock helped set up and run BDP’s London office before going on to launch his own practice, Rock Townsend, in 1971 with fellow BDP architect John Townsend.

Bottom left – John Townsend; Bottom right – David Rock; Top right – Alistair Hay; and Top left – Charles Thompson. Photo: Rock Townsend

Among Rock Townsend’s most renowned works was Angel Square, in Islington, north London, a Postmodern office block featuring an Italian campanile-style clocktower.

After two terms as RIBA vice-president, Rock took the helm of the organisation from 1997 to 1999. He told the AJ during this spell: ‘I like a reputation as a fighting president – I have nothing to lose.’

In 1998, he described a London Council brief as ‘pathetic’ and ‘one of the poorest documents I’ve ever seen’.

Roger Pollard

Photo: Pollard Thomas Edwards

Pollard Thomas Edwards co-founder Roger Pollard died in November at the age of 88.

Between stints studying at the Bartlett, he worked for James Cubitt and Partners in London and the Far East before partnering with Bill Thomas and John Edwards to found the practice bearing their names in 1974.

For the next decade, all the partners worked in the same room. Thomas said Pollard brought ‘lightness’ and ‘perspective’ to their work.

‘Uncontrolled enthusiasm, tempered by genuine warmth, ran through everything he did,’ added his co-founder.

Pollard Thomas Edwards maintains its reputation as a residential architect, and its website lists awards spanning 50 years from 1975 to the current day.

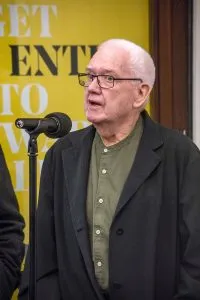

Terry Farrell

Postmodernism pioneer Terry Farrell died in September, aged 87.

His work changed the London skyline thanks to buildings including the MI6 headquarters in Vauxhall, the TV-am headquarters in Camden and the Embankment Place development above Charing Cross railway station.

Photo: Terry Farrell / Alan Williams

Farrell founded his own practice, initially known as Terry Farrell & Partners and more recently simply as Farrells, in 1980. This outfit worked around the world, including on large-scale transport hubs in China as well as at home.

Farrells, the practice, said in a statement that its founder was a ‘maverick, radical and non-conformist’, and that he was ‘never quite part of the “architecture club”, often going against the establishment’.

Nicholas Grimshaw

Nicholas Grimshaw, the pioneer of High-Tech architecture best known for the Eden Project in Cornwall and the International Terminal at London’s Waterloo station, also died in September, aged 85.

After working with Terry Farrell for 15 years, Grimshaw set up his own practice in 1980. Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners became Grimshaw Architects and now employs more than 650 people with offices in Los Angeles, New York, London, Doha, Dubai, Kuala Lumpur, Melbourne and Sydney.

Photo: Grimshaw/Rick Roxburgh

The practice described Grimshaw as a ‘man of invention and ideas’ who would be ‘remembered for his endless curiosity about how things are made and his commitment to the craft of architecture and building’.

He said in 2018: ‘My life – and that of the practice – has always been involved in experiment and in ideas, particularly around sustainability; I have always felt we should use the technology of the age we live in for the improvement of mankind.’

Kongjian Yu

Photo: Turenscape

Sponge city pioneer Kongjian Yu died in September at the age of 62.

The professor at Beijing University and founder of landscape architecture practice Turenscape received the Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize in recognition of his work developing the sponge city concept for mitigating urban flooding and augmenting urban climate resilience.

Yu told the AJ’s Robert Wilson earlier this year that growing up on a farm in rural China had ‘shaped my understanding of the relationship between people and the land’.

He added: ‘Addressing global challenges such as urban flooding, climate change and ecological degradation requires more than technical solutions – it demands a shift in mindsets. Teaching, whether through universities, books, projects or public engagements, is the foundation of my mission.’

Alan Berman

Co-founder of Berman Guedes Stretton (BGS), Alan Berman died in September at the age of 76.

Born in South Africa in 1949, he moved to the UK 13 years later, before securing a place and a sports blue at Clare College, Cambridge, in 1968 to study architecture. He switched to University College London for postgraduate studies and went on to form Berman Guedes Architects in the 1970s and BGS in 1984.

Photo: Peter Searle

The latter practice worked on several higher education schemes. At Wolfson College, Oxford, Berman extended Powell & Moya’s original Modernist buildings with what college bursar Richard Morin called ‘a firm steering hand’.

The studio also helped deliver Richard Meier’s first house in the UK – a huge country home in Oxfordshire, which was completed in 2016.

Graham Morrison, co-founder of Allies and Morrison, said Berman ‘had a clear-headed, logical mind yet never lost his passion for architecture and its detail’. Photographer Matthew Blunderfield wrote in the AJ that Berman’s ‘buildings, words and mentorship had quietly shaped not only the architectural fabric of colleges but the intellectual lives within them’.

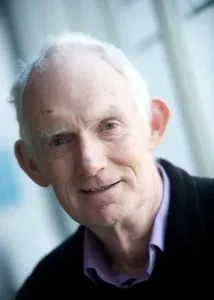

Andrew Saint

Photo: Lily Saint and Catherine Leopold

Architectural historian and heritage champion Andrew Saint died in July, aged 78.

He was a leading authority on Victorian architecture and, as a member of The Victorian Society, a keen campaigner for the preservation of 19th century buildings.

Saint published several books, including Richard Norman Shaw; Image of an Architect; Towards a Social Architecture: the role of school-building in post-war England; and Not Buildings but a Method of Building: the achievement of the post-war Hertfordshire school building programme.

He became professor at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Architecture in 1995 and taught at the institution for more than a decade.

Cambridge’s Department of Architecture said he continued to mark dissertations and give lectures in his retirement and was a ‘friend and supporter of the faculty’.

‘He will be sadly missed,’ it added.

Léon Krier

Poundbury architect Léon Krier died in June at the age of 79.

Born in Luxembourg shortly after the Second World War, Krier moved to London in the 1960s to work for James Stirling and spent much of the following two decades teaching at the Architectural Association and the Royal College of Art.

His 1988 masterplan for the Poundbury new town in Dorset for the then Prince of Wales – now King Charles III – brought Krier a mixture of fame, acclaim and derision.

His Neoclassical urban extension of Dorchester has remained controversial and is yet to be completed, although it is home to more than 5,000 people and said to be contributing almost £100 million to the local economy.

Photo: Jackie Matthews/Shutterstock

Nicholas Boys Smith, chairman of urban design consultancy Create Streets, said he was ‘very saddened’ to learn of Krier’s death.

‘He is probably the most consequential urban and architectural thinker of our era,’ Boys Smith added. ‘As an architect, urban designer, theorist and planner, his career was foundational for the sustainable, human-scale and traditional place-making renaissance that is now, thank heavens, under way.’

Ricardo Scofidio

Photo: Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Ricardo Scofidio, founding partner of US design studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro (DS+R), died on 6 March, aged 89.

He and his wife, Elizabeth Diller, won the Royal Academy’s Architecture Prize in 2019, when they were recognised for their ‘inspiring and enduring’ contribution to building design.

Alongside fellow architects Charles Renfro and Benjamin Gilmartin, Diller and Scofidio were responsible for the High Line in New York and its sibling project, The Tide on London’s Greenwich Peninsula.

The practice is also behind the V&A East Storehouse in London’s Olympic Park; and London West Wall, a controversial mixed-use scheme for the former Museum of London site.

His practice said following his death: ‘The firm’s partners and principals, many of whom have collaborated with him for decades, will extend his architectural legacy in the work we will continue to perform every day.’

Aga Khan IV

In February, The Aga Khan IV, a lifelong advocate for Islamic architecture, died aged 88.

Prince Karim al-Hussaini was spiritual leader of the world’s Ismali Muslim community. He also spent billions of dollars on homes, hospitals and schools in developing countries.

In 1967 he founded the Aga Khan Foundation, which would later become the Aga Khan Development Network that employs 96,000 people across more than 30 countries and channels $1 billion per year into projects including hospitals, schools, universities and climate and cultural initiatives.

Photo: AKDN

He was behind the creation of Aga Khan Centres, established worldwide as places for education, knowledge and cultural exchange. Seven years ago he opened a Maki & Associates-designed centre in London’s King’s Cross.

In 1977, he established the Aga Khan Award for Architecture through the foundation. This is given every three years to projects that ‘set new standards of excellence in architecture, planning practices, historic preservation and landscape architecture’.

Farshid Moussavi, founder of Farshid Moussavi Architecture, who designed the Ismaili Centre in Houston, Texas, paid tribute, describing The Aga Khan as ‘a visionary leader who dedicated his life to improving the quality of life for individuals and communities worldwide, regardless of origin, faith, or gender’.

Dennis Crompton

Photo: David Jenkins (Circa Press)

Archigram member Dennis Crompton died in January at the age of 89.

Born in Blackpool in 1935, he studied architecture at Manchester University before forming part of the avant-garde 1960s architectural group that was eventually awarded a RIBA Gold Medal in 2002.

Crompton taught at the AA for more than three decades and later at the Bartlett, as well as regularly delivering lectures in the USA and Europe.

When the AJ reported that Archigram’s archive was to be sold to modern art and design museum M+ in Hong Kong for £1.8 million, Crompton disclosed that the valuable works had been mostly stored in his house ‘under various beds and in cupboards’.

Fellow Archigram member Peter Cook called Crompton a ‘highly honourable man’ who was passionate about his home town and had an ‘enviable practicality,’ yet was ‘as much a dreamer as the rest of us’.

‘He was quick to rise to any occasion and go along with the absurdities of the Archigram world, right to the end,’ he added.

Richard Gibson

Photo: Gibson family

Shetland-based architect Richard Gibson, whose architecture was described as ‘characterised by care’, died at the end of 2024. His passing, at the age of 89, was widely reported at the start of this year ahead of a 16 January funeral.

Originally from London, Gibson left a position at Camden Council to take up the post of Deputy County Architect on Shetland in the late 1960s.

In 1972 he founded his own practice, Richard Gibson Architects, through which he became known for low-rise housing that befitted the sometimes harsh coastal environment of Shetland.

Gibson was also respected for his public architecture, including schools, museums and civic pavilions and in 2010 was handed a lifetime achievement award by the Royal Institute of Architects in Scotland.

Architectural critic Rowan Moore praised Gibson’s work as ‘characterised by care with the shared spaces between homes and by a responsiveness to the landscape and constructional traditions of Shetland’.

Nick Brett, Gibson’s former co-director at Richard Gibson Architects, said he and his wife Victoria ‘brought colour to Shetland in both an abstract and literal sense’.

Gibson himself said architecture was ‘not about designing icons but making a framework for people to live their lives’.