The issue of cholesterol is a lot more complicated than most people think – there are as many as eight different blood tests for particles that carry cholesterol or other fatty substances

It’s nearly the start of a new year and many of us are planning our resolutions. One that I’ve been weighing up is whether to get a cholesterol test.

My dad had a heart attack at a relatively young age, and so I’m likely to be at higher risk myself.

The NHS says most people should have such a test once they turn 40, as high cholesterol raises the risk of heart attacks and strokes. But the threat could be reduced by lifestyle changes or taking cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins.

At 54, I have been putting this off for too long. Part of the reason I’ve delayed is that, as a health journalist, I’ve become aware that cholesterol is a bit more complicated than implied by the health messaging on this topic.

For starters, it’s too simplistic to talk of the dangers of “high cholesterol”. There are different kinds of cholesterol, and while most are thought to raise heart attack risk, there is one form that seems to be protective – leading to the ideas of good cholesterol and bad cholesterol. And that’s not the half of it.

Tests can give as many as eight different measures of the various particles in the blood that carry cholesterol or other fatty compounds, which all have subtly different implications for health.

Chemically, the compounds are called lipids, so the results are referred to as a lipid profile.

For one person, some of the measures may indicate they are at low risk, while others could say the opposite. Frustratingly, doctors disagree about which ones are the most important.

Then there’s the statin question. Some studies suggest they can cause side effects, including muscle pains and fatigue. I don’t want to take a test that leads to me feeling rotten if the results can be unreliable.

So, my New Year’s Resolution for 2026 is to do something I have been putting off for a while: get to the bottom of cholesterol, testing and treatment, and then make an informed decision about it.

Simple cholesterol story is wrong

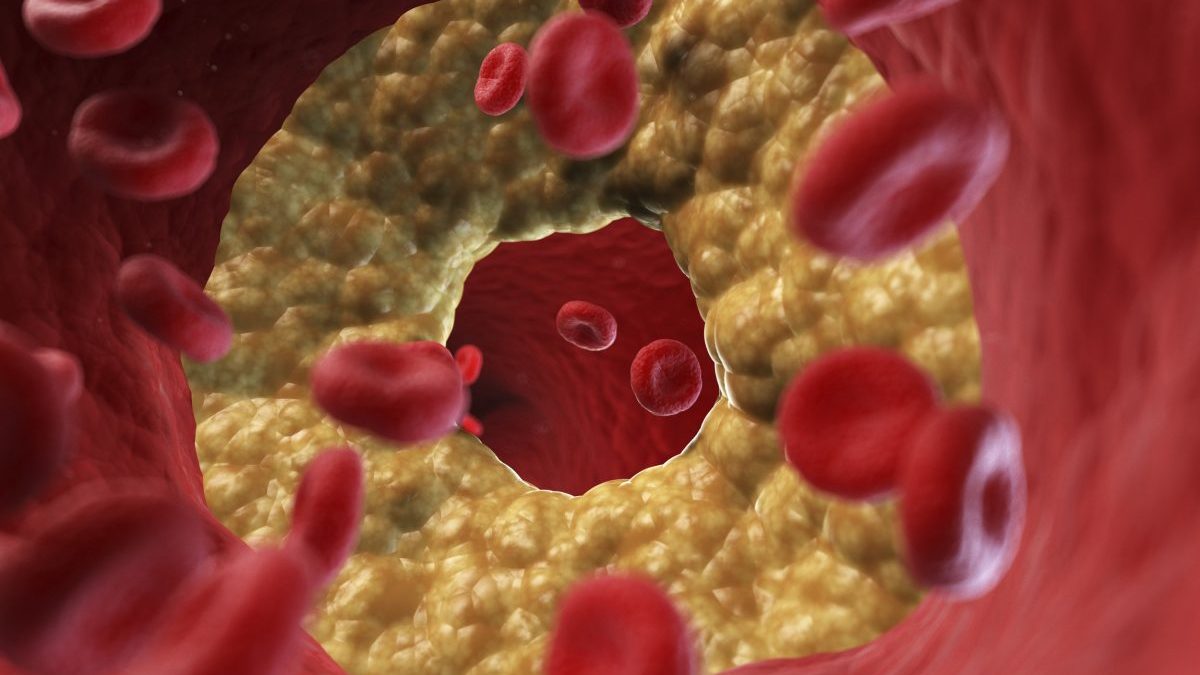

The original version of the cholesterol story is that it is a dangerous fatty substance that can stick to the walls of your arteries, forming plaques, like the way limescale in water can fur up pipes. The plaques are what cause heart attacks.

This was what led to advice in the 1980s that people like my dad, who survived his heart attack, should avoid eating foods high in cholesterol such as eggs.

But doctors today acknowledge that picture of cholesterol is misleading. It isn’t a toxin, but an important substance in the body, carrying out several functions, including as a building block of cell membranes and a starting material for several hormones.

For most people cholesterol levels are not affected by cholesterol in food (Photo: Tatiana Maksimova/Getty)

For most people cholesterol levels are not affected by cholesterol in food (Photo: Tatiana Maksimova/Getty)

Cholesterol is constantly being shuttled about in the blood. It has to be transported inside protein-covered particles because otherwise it would not be water soluble, and blood is mostly water.

Some cholesterol gets into the body from our food. Along with dietary fat, it is first sent to the liver – the body’s master controller of lipid metabolism.

But most of the body’s cholesterol is actually manufactured by the liver. So for most people, the old advice we should avoid foods with cholesterol is now acknowledged as a mistake. If you consume little cholesterol, the liver will just make more of it to compensate.

Total cholesterol hides key details

That’s not the only way that the cholesterol story has changed. Doctors no longer believe the blood’s total cholesterol level governs the build-up of dangerous plaques. Instead they are interested in the relative amounts of the various particles.

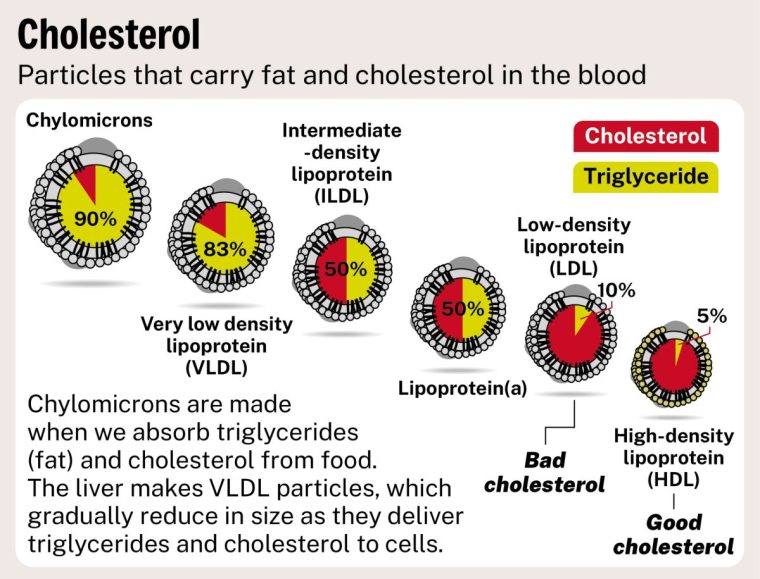

These carry different amounts of cholesterol and come in a range of sizes. They can be thought of as like the mix of traffic on the roads, with vehicles ranging from the biggest oil tankers, through buses and vans, down to the smallest cars.

To get to grips with cholesterol testing, we need to get familiar with this vehicular fleet – so buckle up. To take them in decreasing size order, the oil tankers are particles called chylomicrons, the first stage of fat transport after it is absorbed from food.

Chylomicrons are balls of mostly triglycerides – the chemical name for fat or oil – and a dab of cholesterol.

With a width of 1 micrometre, or a thousandth of a millimetre, chylomicrons can be seen through a small microscope. Their numbers soar after eating, so much that if a blood sample taken after a fatty meal is refrigerated overnight, the chylomicrons form a creamy layer floating on the top.

In the body, though, they don’t hang around. In the hours after a meal, chylomicrons whizz through the bloodstream, gradually shrinking as they deliver triglycerides to cells for fuel or storage. It may be demonised, but for the body, fat is the most efficient energy source.

When small enough, chylomicrons are taken up by the liver again, which after some tweaks, spits them out as slightly smaller particles, called VLDLs. These continue circulating in the blood, gradually delivering more of their triglycerides and becoming a sequence of smaller and denser particles.

How bad cholesterol turns good

The most numerous of these, called LDLs, are the ones your doctor is referring to if they say you have too much bad cholesterol. That’s because LDLs can bind to artery walls and release their load of cholesterol, forming the dangerous plaques.

Once they have shrunk further, in another pass through the liver, LDLs get turned into HDLs, and these are what get called good cholesterol. HDLs are thought to do the opposite of LDLs, binding to plaques and “sucking out” cholesterol, to bring it back to the liver.

Typically, an NHS cholesterol test measures at least four things: the total cholesterol in your blood carried by all these particles, the amount in HDL, the amount in LDL, and the amount of triglycerides.

The orthodoxy is that the key determinant of plaque growth – and therefore how likely you are to have a heart attack – is the amount of LDL in your blood; but this can be somewhat compensated for if you have high HDL. To take both things into account, doctors work out the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL.

They then plug that value into an equation that also weighs up whether you are overweight, smoke, and so on, to calculate your heart attack risk. If it is above a certain level, you will be advised to start taking statins, which reduce LDL.

Bad cholesterol may not be worst danger

There are at least three controversies about this approach. The first is that not all cardiologists agree that the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL is the best way to gauge our risk of plaques.

Some say that, rather than the amount of cholesterol, it is actually the number of LDL particles that governs how likely plaques are to form. LDLs vary in size and having lots of small particles is worse than fewer large ones, because that gives more chances for each one to stick to a plaque and deposit cholesterol.

“If there’s more particles on the road, they’re more likely to crash into the barrier and get caught,” said Dr Scott Murray, a cardiologist at University Hospitals of Liverpool and a former president of the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation.

Particle numbers can be measured with a separate test for something called Apo B, which is the protein on the surface of the particles. Apo B and LDL results are usually similar – but are different in about a fifth of people, according to guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Apo B is more accurate in people with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and in people with high triglycerides or very low LDL.

But if you want to know if you have high triglycerides, there’s another hitch with the NHS test – the triglycerides result will only be accurate if you take the test first thing in the morning, after going without food for 12 hours. Otherwise, the test will detect the surge that happens after eating.

The Apo B test is usually only available through the NHS for cardiologists, not GPs, but it can also be bought online. “The Apo B test is probably superior, but [isn’t yet] part of routine clinical practice,” said Professor Ian Graham, cardiologist at Trinity College Dublin who helped write the ESC guidelines.

When good cholesterol is really bad

There’s a further drawback with the basic NHS lipid profile. The orthodoxy is that the higher your HDL levels, the better – which is after all why it was named good cholesterol.

But it has recently emerged that very high HDL levels are just as bad as very low levels. If you plot a graph of HDL and risk of death, rather than a straight line going down (as was thought), it is in fact a U-shaped curve that bends back up again.

It is not clear why very high HDL is harmful, but it creates a problem. Remember that equation doctors use to calculate your risk of plaque formation? It assumes that the higher your HDL, the better.

This means that people with high HDL would be falsely reassured they are at low risk. “Most doctors won’t be aware of that – they’ll just plug the numbers in,” said Professor Kausik Ray at Imperial College London, former president of the European Atherosclerosis Society.

The other bad cholesterol that gets overlooked

A third criticism of NHS lipid panels is they ignore the impact of a further type of particle called Lp(a) – pronounced “LP little a”. This is similar to LDL, but it has an extra peptide chain stuck to the outside, which promotes both plaque formation and blood clots.

This makes Lp(a) especially dangerous for heart disease risk – and an alarming one in five people have high levels. This is genetically determined and not affected by diet. “There’s less of it, but it’s a lot nastier,” said Professor Ray. “If LDL is like having 100 bullets, LP(a) is like a bazooka.”

High cholesterol raises the risk of heart attacks and strokes (Photo: Yuichiro Chino/Getty)

High cholesterol raises the risk of heart attacks and strokes (Photo: Yuichiro Chino/Getty)

Both European and US guidelines say everyone should have their Lp(a) levels tested, but in the UK, GPs can’t usually offer this – the test needs to be either ordered by a cardiologist or paid for yourself.

But it does seem worth doing to me, as while Lp(a) isn’t affected by statins, two new medicines have recently become available that lower it and more potent versions are in late-stage trials.

Even if you don’t tackle Lp(a) with drugs, it is still possible to lower your total heart risk by improving your lifestyle – for instance, by stopping smoking, drinking less, and so on.

Lipids are not the only risk factor

You might think that as I dug deeper into the potential problems with the NHS test, I would have been put off having it.

In fact, the opposite has happened, and I’m planning to go ahead. I was struck by how the cardiologists who explained the limitations of the NHS lipid profile to me were adamant that it is still helpful most of the time, and better than staying completely ignorant.

There’s nothing to stop me from getting the test first thing in the morning, so it will be accurate about triglycerides – and I plan on paying for supplementary tests for ApoB and Lp(a), at about £60 each.

If the results suggest I need to start taking statin medicines I think they are worth a try – after all, most people don’t get side effects. “Statins are such a potent mechanism to protect yourself,” said Professor Manuel Mayr at Imperial College London, who takes statins himself. “Why would you not use them if you are at risk?”

Your next read

The other thing to remember is that cholesterol is only one aspect of your heart disease risk – other things are important too, like smoking, drinking, diet, weight and exercise levels. “Rather than getting too tied up in cholesterol metabolism, the name of the game is total risk,” said Professor Graham. “You can attack total risk from many angles.”

I don’t smoke, but like most people, my diet, drinking and exercise levels probably have room for improvement. It seems that getting a cholesterol test may not be the only New Year’s resolution I’ll have to make.