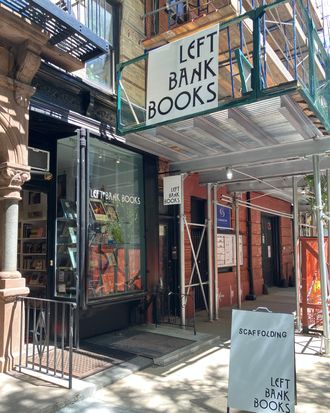

For two years, a teensy bookstore sat under scaffolding, which the owners say deterred shoppers and cut off their light.

Photo: Erik DuRon

Jess Kuronen first noticed the low, piercing sound toward the end of 2021. It was loud enough to drown out the fuzzy punk she often played at Left Bank Books, the Perry Street shop she runs with her business partner, Erik DuRon. Customers would hear it and startle, putting down a chapbook by Audre Lorde or a Kathy Acker first edition to ask, “What is that?” Madeleine Alpert, who works part time at the store, described the sound as similar to dental drilling but more persistent: “Like sonic warfare.”

The drilling was coming from the massive construction project next door, which eventually gave way to cartloads of rocks and dirt that wheezed out dust that clogged the air-conditioner. Kuronen started to curse the plexiglass shelves that made each speck visible. “We would dust. I would dust. Erik would dust,” she says. “And then a day later we would dust again.” Scaffolding went up over the front window and stayed there for two years, casting the store in shadow. When I visited on a Friday in July, raw wiring hung on one side of the façade. On the road, a chain-link fence blocked off a parking spot creating the illusion, from afar, that the store itself was blocked off. “That’s a permanent installation,” DuRon told me, adopting the artsy tone of his inventory.

DuRon outside the shop in July after the scaffolding came down.

Photo: Adriane Quinlan

Left Bank sells a tightly curated selection of esoteric titles on art, music, culture, and design and has been in the neighborhood in one form or another since 1992. It moved to Perry Street in 2019, where $8 paperbacks (a memoir by Playboy bunny Suze Randall) leaven the heavier inventory, like a $3,800 book of photographs (Alexey Brodovitch’s Ballet) and $2,000 first edition signed by Langston Hughes. On the Friday that I came by, Patti Smith’s first single (signed, for $2,000) intrigued a customer, who demurred and instead spent $40 on a book of Carlos Mollina polaroids. His daughter bought a hat. “We will sell hats to people who come in and don’t buy a book,” said DuRon. Jacob Elordi wore a Left Bank Books baseball cap during a shoot for GQ. Addison Rae has one, too — a gift from DuRon after she stopped in. The store isn’t Barnes and Noble. It runs on vibe, not volume. And the endless construction was throwing that off.

Vintage magazines and rare or coveted books preen for buyers who wander in and feel inclined to browse. Adriane Quinlan.

Vintage magazines and rare or coveted books preen for buyers who wander in and feel inclined to browse. Adriane Quinlan.

And there is a lot of construction to contend with. Left Bank, at 41 Perry, shares a wall with a former multifamily building that sold for $19.25 million in 2019 with plans to turn it into a single-family home. These double-wide townhomes have already taken over West 11th. Chipotle founder Steve Ells copied Sarah Jessica Parker and Matthew Broderick (No. 273-275) and bought at the end of the street, at West Fourth, while another double sold there for $72.5 million last year. The gut job on Perry Street included plans to dig out the cellar, add a roof deck, and install a Turkish bath. Like so many wealthy buyers in the city, the owners used an LLC, but locals knew who they were, anyway: Robert Soros, the eldest son of George Soros, and his wife, Jamie Singer Soros. When I called her, she said she didn’t know about emails that DuRon said he had been sending her since October and insisted she is doing everything in her power to be a thoughtful neighbor during the renovation. “I can’t wait to move in,” she said.

Google Maps StreetView captured the construction when scaffolding was up.

Photo: Google Maps

“At least they aren’t Fox News people,” said a neighbor, the painter Jo Ellen Van Ouwerkerk. Others were angrier; one called the work “extravagant.” “I’ve been calling it the $20 million starter home,” Kuronen joked. And DuRon wrote an op-ed in the local Village View, a community paper that emerged from its own neighborhood fight. The piece decried the neighborhood’s “ transformation … into a wealthy suburb of finance capital” and said the shop’s sales had fallen in the wake of the construction. (The Soros family had no comment on the op-ed.) Other old-timers were reluctant to alienate neighbors they would soon need to get along with or scorn renovation that looks a whole lot like what they’d done. “It’s hard for me not to feel like a hypocritical hater,” said the film and advertising producer Mindy Goldberg, who has lived on the block since the 1990s. She rented Abel Ferrara’s old apartment, eventually buying the building, renovating it with her architect ex, and raising a family there. Still, the renovation across the street “does feel more intense,” she said.

The closed sidewalk.

Photo: Erik DuRon

The scaffolding came down in June, but the chainlink and orange fencing in the roadway is still up.

Photo: Erik DuRon

“It’s not like I’m naïve,” said DuRon. “I depend on affluent people.” But something had changed. In his op-ed, he described the change on the block as a “hollowing out.” “We need access to good material. We need access to people with taste, but also money,” Kuronen said. “And I’m starting to worry that the taste and money are going separate ways.”

Jamie Singer Soros says she expects to move in soon, certainly by the end of the year. But permits for other brownstone renovations are pasted up and down the block. 34 and 36 both look empty with plywood blocking off doors and windows and permits outlining renovation jobs. Number 46 was listed earlier this year by a broker who said it was “ripe for conversion” into a double and No. 27 is being marketed to future buyers for its “endless possibilities,” including the opportunity for “basement excavation.”

Sign Up for the Curbed Newsletter

A daily mix of stories about cities, city life, and our always evolving neighborhoods and skylines.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

Related