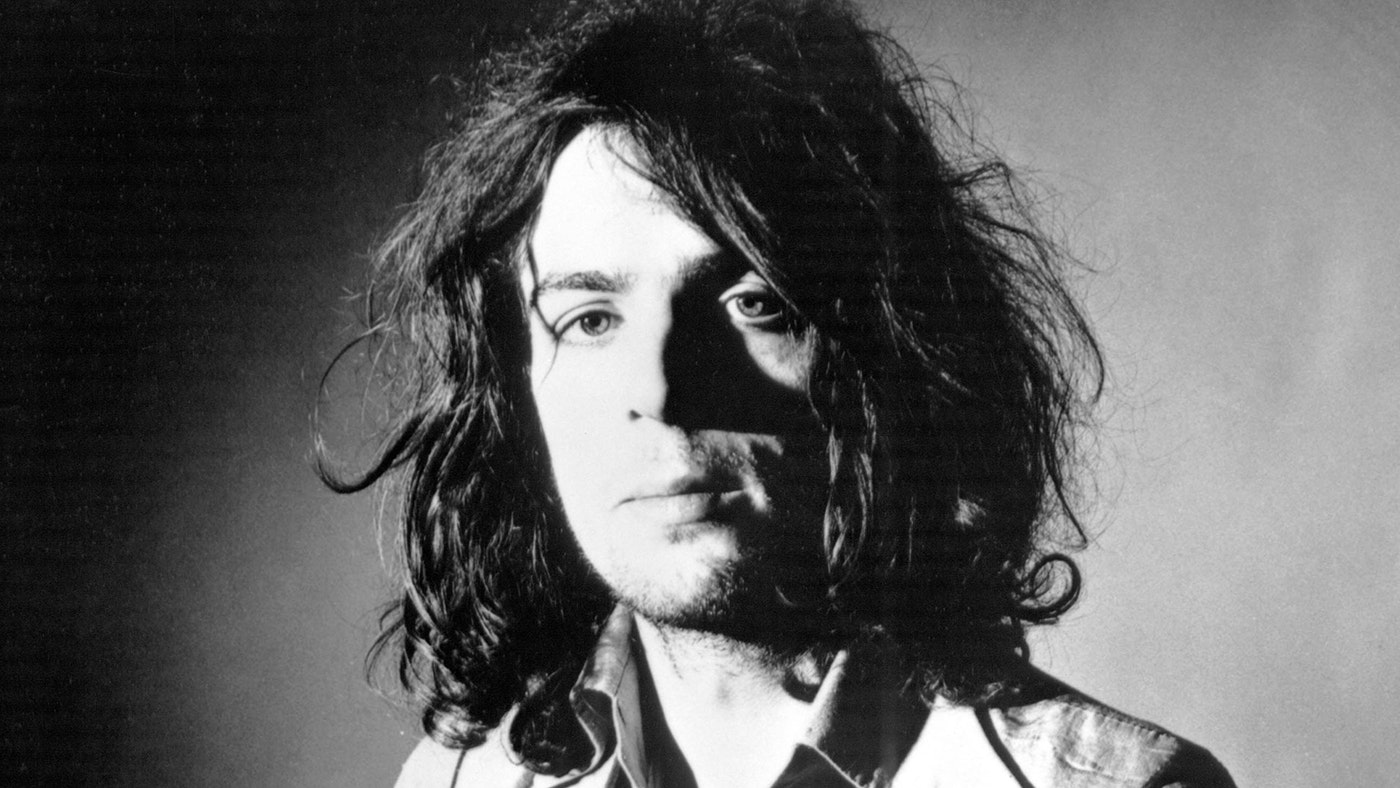

Born in Cambridge in 1946, Roger ‘Syd’ Barrett was not only the creative visionary behind Pink Floyd in the 1960s, but the leading light of the UK’s psychedelic scene itself. Barrett’s kaleidoscopic imagination, alchemising childhood fantasy with cosmos-prodding musical exploration, was captured on Floyd’s 1967 debut, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn. Yet just as quickly as his star ascended, Syd suffered a swift mental deterioration, the pressures of fame exacerbated by his growing LSD use. By 1968 Barrett was out of the band he had formed with childhood friend Roger Waters, and while his two solo albums, 1970’s The Madcap Laughs and Barrett, would provide wellsprings of inspiration for generations of artists from David Bowie and Robyn Hitchcock to The Damned and The Jesus And Mary Chain, he withdrew from public life entirely, returning to Cambridge to live and paint as a virtual recluse cared for by his sister, Rosemary. When Barrett died in 2006, some of his friends and admirers paid tribute to Floyd’s fallen Icarus…

Peter Jenner

Manager of Syd-centric Floyd; produced his last session.

“We were all, in varying degrees, amateurish or incompetent. Yet we achieved something enormous, which had everything to do with Syd’s charisma, his creativity and his songwriting. [Co-manager] Andrew King and I had never even sold a packet of biscuits before, but within three months Floyd had the biggest deal EMI had ever given to a new pop band. It was Syd’s talent that brought it all together.

“When I think of Syd, I think of two occasions. The first is at Earlham Street, playing guitar, with his book with all his songs in it, reading out the lyrics. And the other image is from the other end. It’s Syd sitting in my flat in Edbrooke Road, near Abbey Road, and writing Vegetable Man because we needed a new single. And he sat there and wrote it, and it was just a description of himself. And that was all inside a year, during which he’d gone from fresh-faced youth to: Christ, what’s happening here?

“Those extraordinary last songs, Scream Thy Last Scream, Jugband Blues, Vegetable Man, are not fun. But they’re great works of art, a depiction of a state of mind, up there with the old Van Goghs – the ones with the blue sky and cornfields and the birds. You look at that and think, Fuck, is that how he was feeling? Is that where his mind was?’

“Syd put a unique combination of things together, and created something that has affected the development of British music and art. He made his choices for whatever reason. Maybe he’d had enough. Maybe he wanted to just waddle around in Cambridge, to not have all the cares about career choices and taxmen, and servants, and all that shit- ambition and greed.”

Mick Rock

Syd’s court photographer and confidant.

“I met Syd in December 1966 at the Cambridge Art College’s Christmas party. I was studying Modern Languages at Cambridge University. Some people from town and took me to see their friend Syd Barrett who had a band called Pink Floyd. I don’t remember anyone else on stage that night. It was all Syd. He sung, he played, he was the focal point and he was the most charismatic.

“After the gig, my friends took me to meet Syd and we went to his mum’s house. There was a record player, music was being played very loud. Syd loved jazz, the Stones, Dylan. Some of his abstract paintings were there too. What I remember was that Syd laughed a lot. He was a very happy, communicable guy. We talked about science fiction, Eastern mysticism. We were kids, 18, 19, but we knew we were on the cusp of some- thing, we felt alien but special. His fame happened incredibly quickly. Christmas 1966 he was subterranean, summer 1967 he was heading the 14-Hour Technicolor Dream. Syd withdrew because he liked to improvise, he didn’t want to go out and play the same songs every night.

“By the time I took my first pictures of Syd in 1969 he’d been out of the band for a year. He was very easy to work with, and when in 1971 I captured him in his mum’s garden, he was relaxed. If Syd hadn’t stopped playing with the Floyd, though, he probably would have died. He was fragile, a gentle soul who somehow got stuck and couldn’t get out and the only way to preserve himself was to withdraw. Syd liked to laugh. I remember him that way.”

Elton John

Today a superstar, then Pinner’s prime Syd devotee.

“I saw The Pink Floyd at UFO in Tottenham Court Road in 1967 and I was blown away. I’d never seen anything like it. The visual aspect of the show alone was unbelievable. It was extremely exciting because it was a pretty small club anyway… an amazing thing, visually and musically too. Obviously, Syd’s death [in 2006] was very sad. To me he was rock’s first true casualty. Because of that he’ll be one of those people, like Nick Drake and Marc Bolan, whose legend will live on forever. You can hear Syd in early Blur records and in lots of other different places. And that’s the nicest thing one can say about what he achieved: the man won’t ever be forgotten.”

Barry Miles

The counter-culture’s resident Boswell.

“I first saw Syd play at the Spontaneous Underground at the Marquee in the spring of 1966. There’d been a lot of discussion about combining rock’n’roll with electronic music and here was a group clearly headed in that direction. Syd was not a guitarist in the normal ‘rock’ mode. He was interested in the textures and effects. was a painter and brought an artist’s approach to his solos. One of the few conversations I had with him was about how to incorporate the ideas of John Cage into rock and make it an art form instead of just ‘pop’. Everyone knew Syd. The communal house at 2 Earlham Street, just off Charing Cross Road where he and his girlfriend, Lindsay [Corner] lived was a typical 1966 hippy pad, from its purple door to the psychedelic graffiti on the walls. Syd often sat up on the roof, looking out over Covent Garden, playing his guitar and composing songs. This was his most creative period lyrically and possibly the happiest time of his life.”

Dave Brock

Hawkwind’s space lord, and fellow sonic adventurer.

“I was busking in London when I first saw Pink Floyd at the UFO club, but the next time I heard them properly was when Arnold Layne came out. I was in Holland and that track sounded great, totally different from everything else. Syd’s lyrics were down to earth, humorous and unique. To me he was very much like Bob Calvert [Hawkwind’s bipolar poet-in-residence, who died in 1988]. He suffered from incredible highs and crushing lows. That’s what happens when you’re touched by genius. I think Syd suffered in that same way as did [the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band’s] Viv Stanshall. All three were unique performers. Syd made some great, timeless music that changed a lot of things.”

Paul Weller

The Modfather, covered Apples And Oranges in The Jam.

“Syd was a unique songwriter. I loved his guitar style and the sound he got. He looked amazing, he was a really beautiful kid, and his vision and where his mind was at was amazing too. He opened up possibilities. I was nine or 10 when I first heard See Emily Play and I thought it was fantastic. It had so many different colours and textures. Syd had such an otherworldly quality to him. Those first singles – Arnold Layne, See Emily Play, Apples And Oranges- and The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn were amazing. His solo work too – Dominoes, Golden Hair, most of The Madcap Laughs – are magical. But when he disappeared, people reduced him to this tragic, figure, ‘the doomed star’, but they failed to see he was a human being going through mental anguish. He shone so bright for such a short space of time, everyone’s vision of him is still trapped in that time, we only think of Syd as he was on the sleeve of the first album. All I know is that he’s very important to me.”

Wayne Kramer

The MC5’s street fighting sonic architect.

“I first heard Syd in Floyd in 1967 when we were all around Wayne State University – the Ladbroke Grove of Detroit, full of poor people, students and beatniks. We went over to [manager John] Sinclair’s place. He had a compound that was in an old dentist’s office and he played us that first album. I’d been listening to Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor and Albert Ayler, but Pink Floyd were confirmation that rock music was breaking new ground too. Most British guitarists were American blues aficionados reintroducing Americans to blues, but Syd didn’t come from there. His approach was more experimental. I also dug Floyd’s sense of community. They were like the MC5’s British brother band, playing community shows and creating cultural events. There is an undeniably romantic aspect to his story in that the band carry on and become multi-millionaires and he becomes a recluse. But I applaud anyone who walks away from the music business, because if you stay it probably will drive you insane. In that respect, bless Syd.”

Captain Sensible

The Damned bassist and punk Syd freak.

“The Damned wanted Syd to produce our second album. We wanted to make a psychedelic punk masterpiece and Syd, for us, would have been perfect to realise that vision. At the time we had the same publisher as Syd, Peter Barnes, and Syd hadn’t done anything for years. Peter was really protective of Syd. I think they wanted to coax him back into the studio again and thought this would be the best way of doing it. But can you imagine poor old Syd working with us? The Damned were imploding at the time. It would have been chaos! I fully expected to see him walking through the door of Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row studio, where we were booked into. The door opened and the fucking drummer, Nick Mason, walked in. He said Syd couldn’t make it, he’s not well. We couldn’t get anyone else in because it was Floyd’s studio. Nick Mason wasn’t an unpleasant bloke, mind you. There just wasn’t a meeting of minds. We never got to meet Syd Barrett although there was talk of going round to visit him-not a good idea.”

Robyn Hitchcock

Soft Boy, solo star and one of Syd’s psychedelic sons.

“Syd Barrett left his host body years ago and there were many periods when I thought he had moved into mine, but that was my own fancy. You’ll really find him in his records – not in a banal way, but almost physically, like a trapped personality. There’s an intensity in everything he did. The words, the tune, the way he sang it, the guitar playing that accompanies it, there’s something a little unearthly. It’s something to do with someone not being able to live with themselves. I think there was a power struggle between Syd and Roger – I don’t mean Roger Waters, I mean Roger Barrett- and that Roger Barrett won. By all accounts, he carried on doing studies of watercolours, and painting – he was kind of convincing himself he was still at art school. So he was this hybrid of a small child going around in shorts and a serious old man. Meanwhile, everyone wanted Syd: “We want Syd, where is he?” Imagine somebody that disturbed and sensitive with all these ghouls on his doorstep. It’s not pretty.”

John Frusciante

Red Hot Chili Pepper and born-again Syd fan.

“When I was 15 I took a trip to New Jersey and stayed with a fellow Zappa–Beefheart fanatic, Joey Psychotic. He was also a Barrett obsessive. We listened to Syd for 90 per cent of the time I was there. Syd was one of the most original songwriters I’d ever heard. I purchased everything he was on. When I was 21 and started smoking weed his music took on an entirely different meaning. His music made the unseen parts of reality clear to me. I believed in his world more than the one I saw people around me living in.

“Inspired by The Madcap Laughs, Barrett and Opel, I also began my relationship with acoustic guitar songwriting, which never seemed right for me until my obsession with those albums.I related to his disconnection from his bandmates and his aversion to success. Like him (and many others), I originally thought success was what I was after and quickly found that the light was elsewhere. Not that I knew exactly where the light was, but I knew that chasing success had no value for me. Syd’s work with Floyd is extremely inspiring to me and has something to do with where I’m going. His genius and his pure, childlike spirit make him shine as bright as anyone could. May he be in a world more deserving of him.”

Jim Reid

Jesus And Mary Chain’s mainman, covered Vegetable Man.

“When Bowie covered See Emily Play on Pin-Ups I dug out the original and that was it! I was a fan for life! It was around the time of punk, when Pink Floyd were the enemy, but as soon as you hear those songs you forget about musical politics. If anybody else was to try to write that kind of song, it could be horrible, twee. With Syd it was almost like what was going on in his head went straight down onto tape with nothing in between. I don’t really buy the whole ‘Syd insane’ thing, though. I think he might have got a bit frazzled by taking the wrong drugs in the ’60s but came through them and just didn’t want to be involved. There’s a lot of shit to put up with in a band. We all take it; he didn’t. The Mary Chain covered Vegetable Man – the lyrics are really weird. You can clearly hear that the guy’s falling apart, saying that the clothes he’s wearing are all he is – there’s nothing else. Syd was the soul of Pink Floyd. When he left there was a huge gap, and I don’t think it ever got filled.”

This article appears in MOJO’s deluxe Pink Floyd Special, MOJO The Collectors’ Series: PINK FLOYD ECHOES 1965-2025. More information and to order a copy HERE.

.

.

.

.

.