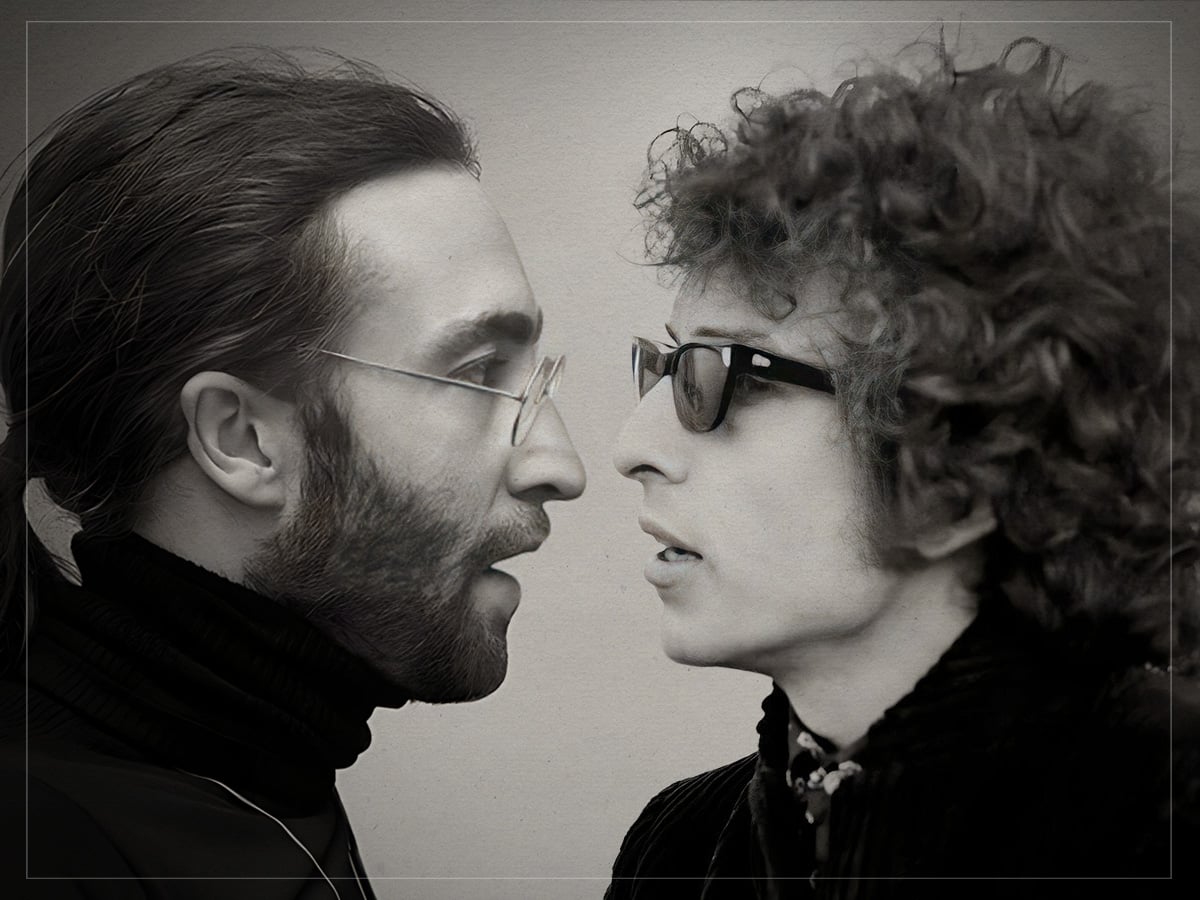

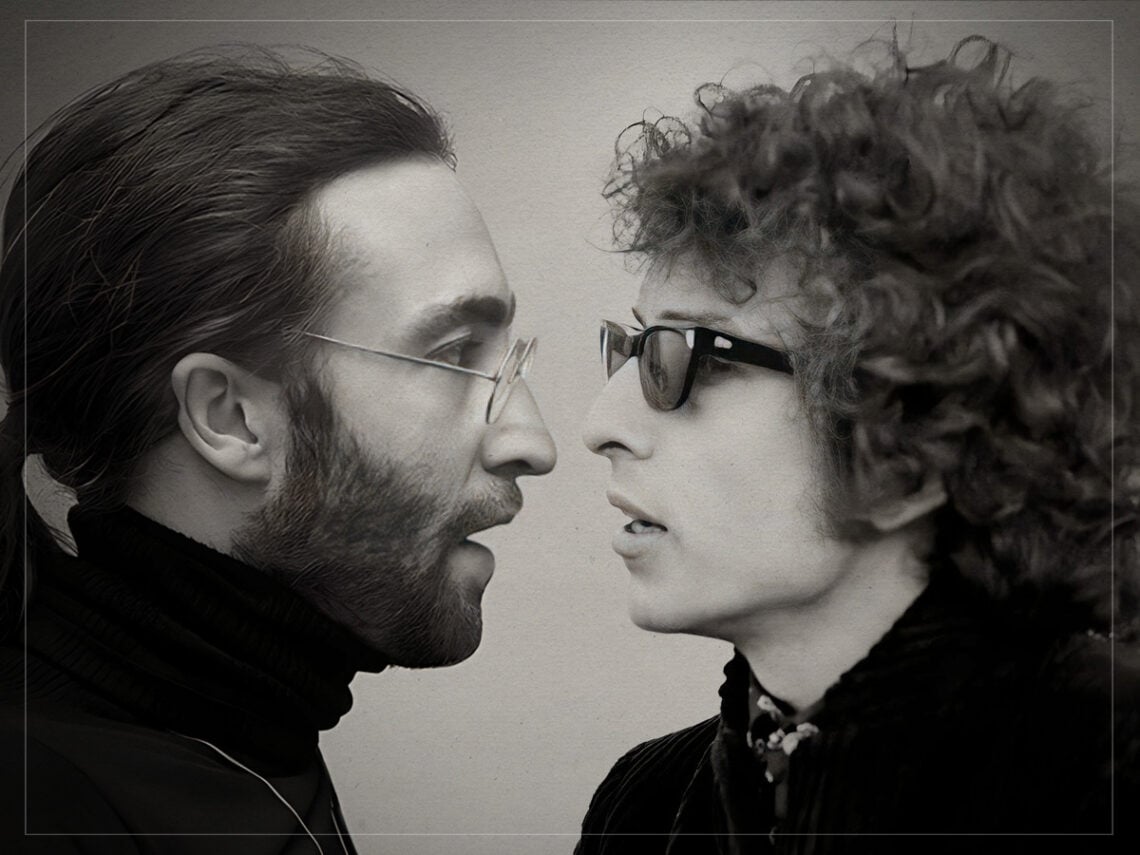

(Credits: Far Out / UMG / Bent Rej)

Wed 14 January 2026 15:07, UK

John Lennon enjoyed many fractious relationships throughout his life. First, there was his mother, then Aunt Mimi, then Paul McCartney, Cynthia, Yoko and the list never ends. While the founding member of The Beatles was known to be a staunch lover, throwing himself wholeheartedly into the peaks and pitfalls of human existence with reckless abandon, he was also just as likely to forget about the experience the very next day, dismissing it for a series of new-cobbled excuses.

One such person provided a similar journey of exploration, adoration and then rejection for the bespectacled Beatle. A man who had not only been a counterpart but had, at one time, been a beacon of light in expression, a pathway forward into a new world of creativity, and just as so many of Lennon’s relationships would, ultimately, leave him unsatisfied. That man was Bob Dylan.

When the pair first met, there was an instant attraction. Each man had been championed as the voice of the restless youth movements, but both men had different approaches. In the earliest sparking moments of the 1960s, Lennon and Dylan had operated as different ignitions. Lennon was a populist who had unshackled a generation to move their bodies in a brand new way. Dylan, meanwhile, was a more cerebral flicker, connecting to a generation of lost souls with his words.

1964 was the moment the two icons clashed over an expertly rolled joint, and the duo influenced one another deeply from the moment it happened. While Dylan could learn a thing or two about how to get your message out to millions and millions of fans, Dylan showed The Beatles, and namely John Lennon, how to find that message, to begin with.

As Paul McCartney once said, “He was our idol.” When they first heard the introspective poetry of the folk songsmith, their world changed. As John Lennon recalls in The Beatles Anthology: “In Paris in 1964 was the first time I ever heard Dylan at all. Paul got the record [The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan] from a French DJ. For three weeks in Paris, we didn’t stop playing it. We all went potty about Dylan.” The Beatles would take Dylan’s form of self-expression in folk music and apply it to pop.

Bob Dylan smoking a cigarette in 1966. (Credits: Bent Rej)

Bob Dylan smoking a cigarette in 1966. (Credits: Bent Rej)

Tracks like ‘Help’ and ‘You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away’ are clearly connected to Dylan’s songwriting approach. Lennon said of the latter: “That’s me in my Dylan period again. I am like a chameleon, influenced by whatever is going on. If Elvis can do it, I can do it. If the Everly Brothers can do it, me and Paul can. Same with Dylan.” But sadly, not everything lasts forever, and the influence and friendship Dylan and Lennon once shared soon began to wane.

“Yoko was never under any Dylan mystique. She never thought much of him either way,” confessed Lennon. “For a period, I was very impressed with him,” the singer revealed. “But I stopped listening to Dylan with both ears after [Highway 61 Revisited] and Blonde on Blonde, and even then, it was because George [Harrison] would sit down and make me listen.” Harrison had become infatuated with Dylan, leaving Britain behind to go and work with him, with the freewheelin’ troubador happy to collaborate. However, Lennon didn’t shut off his old friend completely and still, like the rest of the world, followed the songwriter’s career as he began to flourish in rock and roll.

It had been a big leap for Bob Dylan to go from folk’s undying acoustic hero to betraying those diehard fans and moving into rock. It speaks highly of an ever-evolving artist. However, such a need for perpetual motion will often see the most chaotic of moments occur, and Dylan fans got one as he began to explore the righteousness of rock music and delivered biblical sermons amid his songs when performing live, a style of delivery that first took root in Dylan’s 1979 album Slow Train Coming.

The record included a song that John Lennon would label “pathetic”. ‘Gotta Serve Somebody’, which Lennon deliberately mislabels as ‘Everybody’s Gotta Ge Served’. “Well, I was listening to the radio,” he begins, “And Dylan’s new single, or whatever the hell it is, came on. He wants to be a waiter for Christ,” Lennon adds, laughing to himself and his dictaphone, thereafter his critique becomes a bit more caustic. “The backing is mediocre […] the singing’s really pathetic, and the words were just embarrassing,” he added.

It led to Lennon writing his own song about Dylan, ‘Serve Yourself’, in which Lennon sings: “You tell me you found Jesus/ Christ! Well, that’s great, and he’s the only one/ You say you just found Buddha?/, and he’s sittin’ on his arse in the sun?” It’s a clear role reversal after Dylan had used ‘Positively 4th Street’ to go after Lennon’s remarkably familiar cadence.

The nail in the coffin came a few weeks later when Lennon spoke to David Sheff about Dylan: “Anybody who wants to hear Dylan just because of who he is isn’t gonna understand what Dylan is saying now or then. They’re just following some kind of image. They’re the sheep anyway. Still, the whole religion business does suffer from the ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ bit. There’s too much talk about soldiers and marching and converting. I’m not pushing Buddhism, because I’m no more a Buddhist than I am a Christian, but there’s one thing I admire about the religion: there is no proselytizing.”

Later adding: “You have to think in terms of process. Relying on your own spirit is healthy. If Dylan is into Jesus because of needing to belong, whatever, perhaps the next step will be to see the good of the experience as well as the other side.”

The truth is, religion never really sat well with Lennon. He was far too against any sense of establishment to be indoctrinated into believing a certain set of values for too long, especially a set that he hadn’t himself come up with. Dylan’s decision to follow his faith seemingly told Lennon that he no longer believed in himself. That giving himself over to a heavenly father meant forgetting those who were left on earth. Lennon’s love and loss of figures in his life all seem to revolve around this one social movement.

Abandonment is a terrible thing to have to deal with as a young child, and when Lennon moved in with his Aunt while his mother and father struggled to look after him started a series of events that would be littered across the Beatle’s life. As his mother tragically died so young, so too did Lennon’s innocence, and the faith he once had in people seemed to go the same way. Dylan was just another figure who seemed to leave Lennon alone.

Related Topics

The Far Out Beatles Newsletter

All the latest stories about The Beatles from the independent voice of culture.

Straight to your inbox.