(Credits: Far Out / Columbia Records)

Sun 18 January 2026 15:20, UK

You might think an artist picking their favourite album would be like a parent picking a favourite child. Each album is created, born and raised much like a kid, as musicians try and try to get it right, finally make it and then often have a battle to ensure that the collection of songs is nurtured just as they wish. With so much effort put into each release, you would’ve thought selecting one out of the batch would be impossible. However, when it comes to Paul Simon, he’s as strict and certain in his opinion as a cruel father with a clear case of favouritism.

Some of Simon’s fans or even the most casual listeners might not be able to pick out a favourite. His 1970s albums delivered some real treasure. The 1972 self-titled release has the endlessly catchy ‘Me And Julio Down By The School Yard’. Still Crazy After All These Years in 1975 has the mega-hit ‘50 Ways To Leave Your Lover’, alongside some of his most beautiful and timeless love songs.

After parting from Simon and Garfunkel, the musician clearly had plenty more to say and plenty of ideas to work away at. That made him prolific and seemingly tireless in his excitement towards his own project and the new total control it afforded him. With this attitude behind him, every album feels like a passion project or a real labour of love, capturing a moment in his life. You would have thought that picking a favourite would be an impossible task, but alas.

“Graceland is the peak in my solo career,” he told The Guardian rather matter-of-factly.

It’s easy to see why. The 1986 album contains what are undeniably some of his best songs, like ‘You Can Call Me Al’, ‘Diamonds On The Soles Of Her Shoes’ and the beloved title track, ‘Graceland’. To many, including Simon himself, clearly, this is his opus that truly proved that he didn’t need Garfunkel by his side to create something powerful. But for Simon, the hits don’t really matter. His reasoning is all based on the story and the way a questionable move paid off into something beautiful.

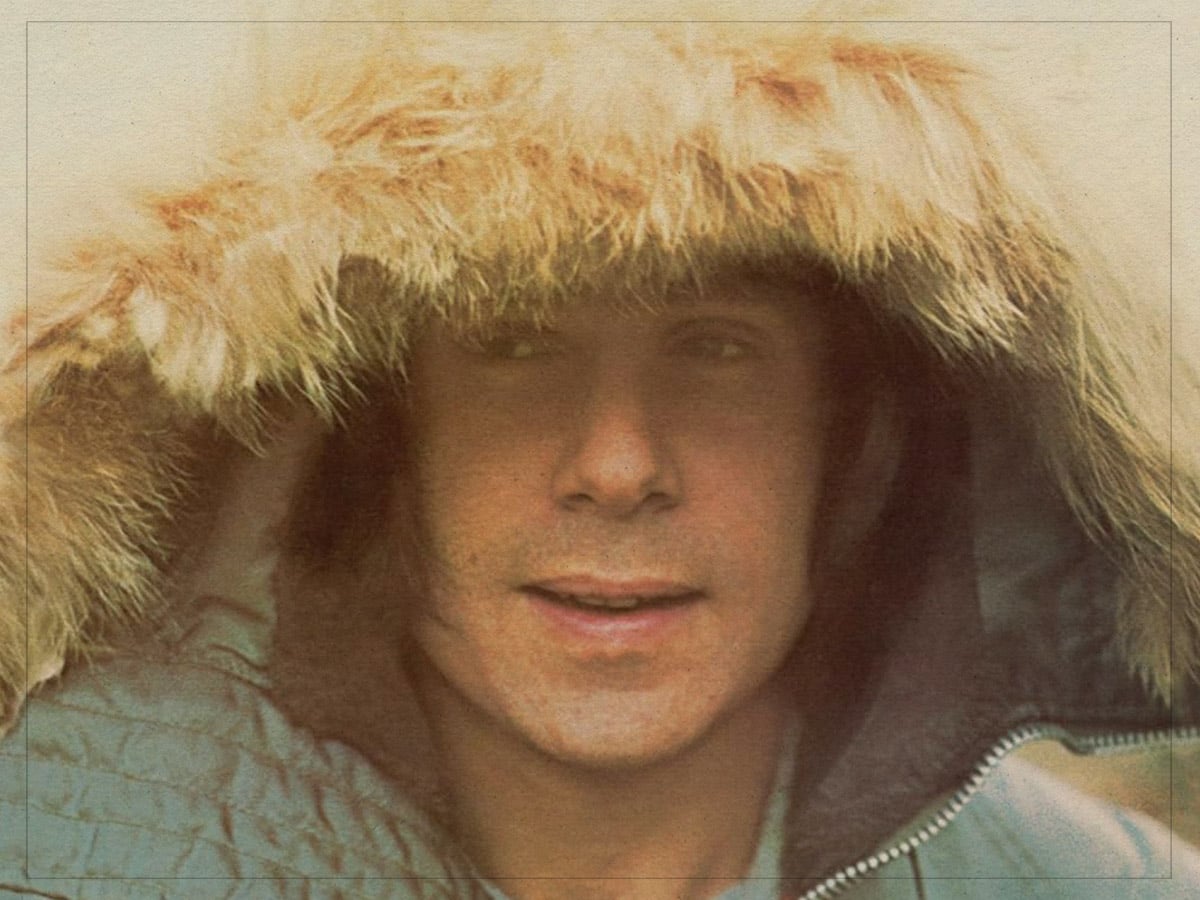

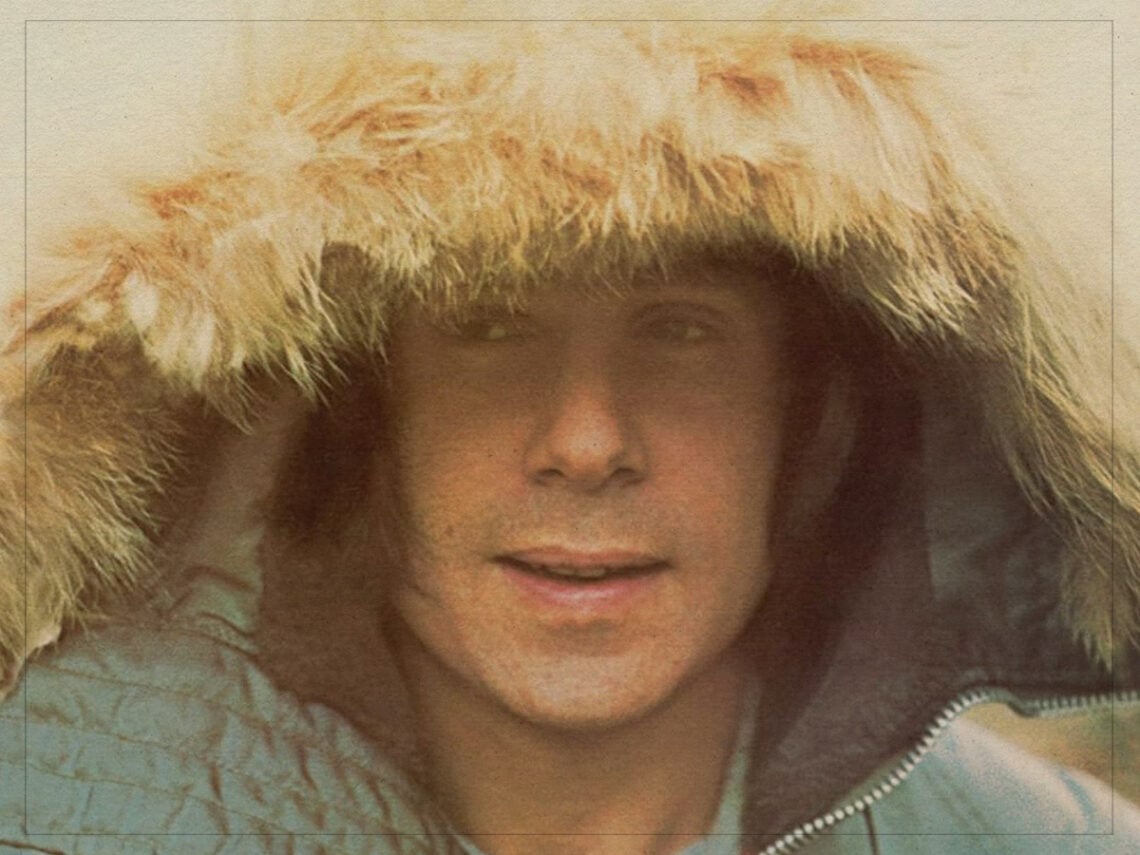

Paul Simon complete with adventurer’s fedora. (Credits: Far Out / Album Cover)

Paul Simon complete with adventurer’s fedora. (Credits: Far Out / Album Cover)

The circumstances that surround Graceland still raise eyebrows. At the time, the musician was condemned by organisations like Artists United Against Apartheid as he chose to record part of the album in South Africa during the apartheid regime. Simon broke the cultural boycott on the country, crossing the picket line simply to go and record.

“When he goes to South Africa, Paul Simon bows to apartheid,” James Victor Gbeho, the former Ghanaian ambassador to the UN, said at the time. “He lives in designated hotels for whites. He spends money the way whites have made it possible to spend money there. The money he spends goes to look after white society, not to the townships.”

This criticism was then tied into the music of the album. Throughout the record, Simon uses traditional African instruments and beats, merging the sounds of South Africa with a more American feel. To some, that was seen as appropriation as the musician broke the boycott, ignored the political climate and simply went to the country to borrow from their culture.

However, the musicians on the LP didn’t feel that way. “We used Paul as much as Paul used us. There was no abuse,” the guitarist Ray Phiri said, “He came at the right time, and he was what we needed to bring our music into the mainstream.” The musicians were also incredibly well paid. Whereas the standard fee in the country at the time was to pay $15 a day, Simon paid the band he assembled $200 a day.

Simon, since the album’s conception, has fiercely defended and loved Graceland. Even when criticism was at its height, condemning his choice to record in the country and then condemning the lack of politics in the lyrics of the album despite the conditions, the musician fought back. “I still think it’s the most powerful form of politics, more powerful than saying it right on the money, in which case you’re usually preaching to the converted,” he said of the record and his decision not to write overtly political songs. “People get attracted to the music, and once they hear what’s going on within it, they say, ‘What? They’re doing that to these people?”

For Simon, all of this makes Graceland his peak. With the situation surrounding him and his decision to record elsewhere, the LP pushed his abilities to write songs and challenged his ear for composing them while bringing in new sounds. While it’s certainly still a questionable take and a problematic move in music history, the musician always seemed to value the power of a good song over political power, seeing the prior as just as much of a stand as any sterilised statement. And on Graceland, he still believes he made a bold and moving one.

Calling Graceland his peak is not Simon crowning a set of singles, it is him crowning a risk that did not come with clean hands. Plenty of artists make their best work in comfort, surrounded by familiar players and familiar rules. Simon did the opposite. He walked into a storm of optics and ethics, and he still insists the record earned its place because the songs arrived carrying something bigger than him, bigger than the argument, bigger than the moment.

That is the tension the album has never escaped and why it still holds its power. Graceland is both triumph and provocation, a masterpiece that forces the listener to sit with two truths at once: the music is luminous, and the context is thorny. Simon’s favourite album is not the one that makes him look best, it is the one that demanded the most of him and still survived the heat. In his mind, that is what separates a great record from a merely successful one.

Related Topics