How, as a researcher, can you use AI tools like ChatGPT in a way that doesn’t compromise your integrity, creativity, and independence?

In the following guest post, Jimmy Alfonso Licon (Arizona State University) explains how he does it, laying out how he approaches his writing process and the roles he assigns ChatGPT in it.

As Dr. Licon describes it, his “resulting workflow is neither purely human nor AI-written.”

Those who make use of AI in their research and writing are encouraged to share their methods and processes in the comments. Also of particular interest is how human-AI “hybrid” works should be treated, institutionally (by journals, universities). Discussion welcome.

(A version of this piece first appeared at Dr. Licon’s newsletter, Uncommon Wisdom.)

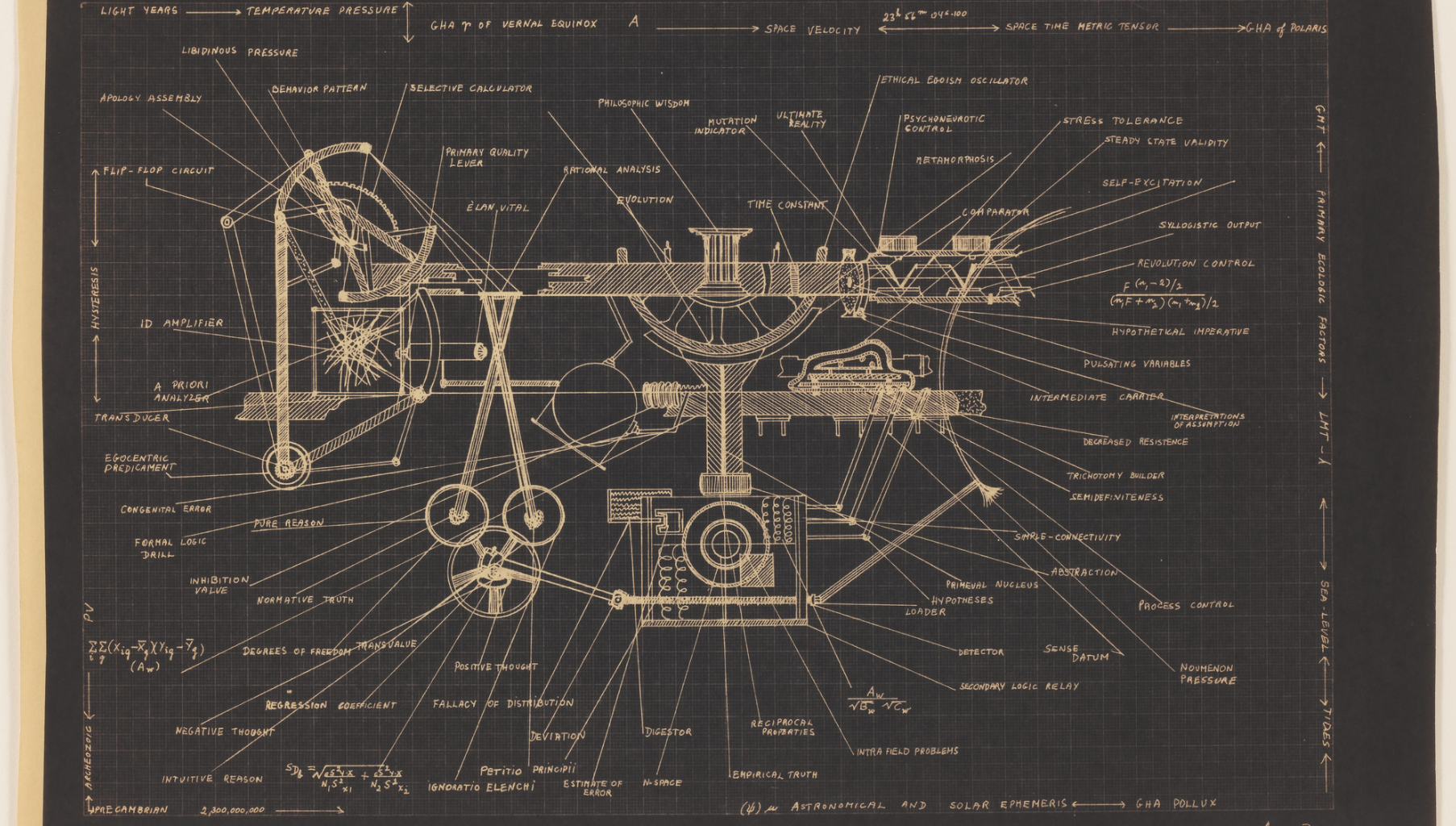

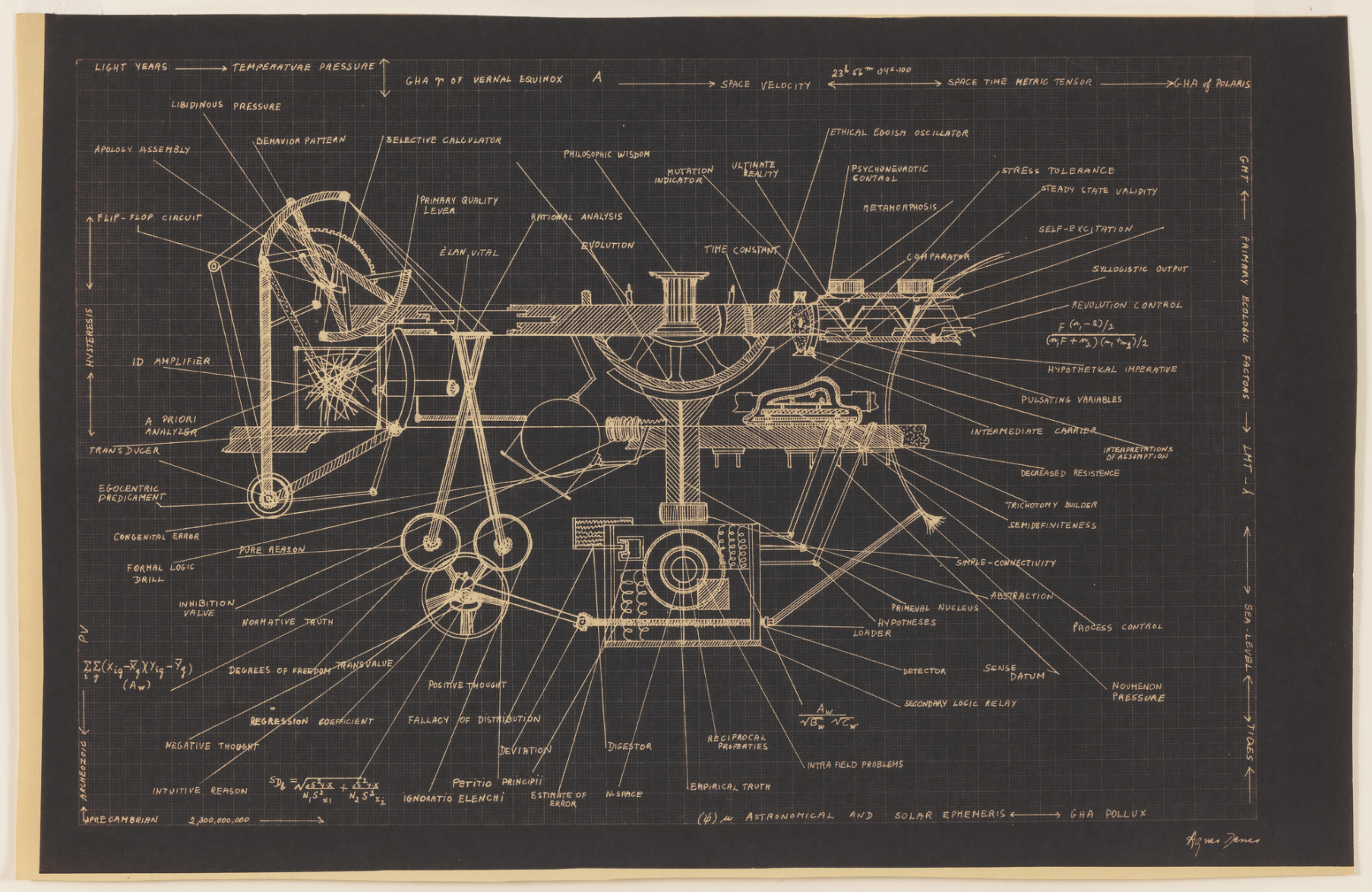

[“Human Hang-Up Machine” by Agnes Denes]

Have Pen, Laptop, and ChatGPT, Will Publish

or How I Use AI Without Sacrificing Creativity and Independence

by Jimmy Alfonso Licon

People sometimes imagine writing as a flash of inspiration, a heroic sprint at the keyboard, and then a finished paper. My own process is considerably less cinematic and much more modular. It involves a pile of printed articles, a pen, a computer, and a large language model. Each plays a specific role. And together, they help me turn a half-formed idea into a shareable, defensible piece of scholarship.

I usually start with a nagging thought. An irritation with a familiar argument, or a pattern I see across different debates, or a question that just won’t leave me alone—something that continues to bug me. At this stage, I begin by writing down a very rough abstract: a paragraph or two sketching the core claim, the basic structure of the argument, and why it might matter. It is only meant to capture the rough intuition. Nothing beyond that. The point is to get the idea out of my head and onto paper where I can see it, poke at it, and at some point, ask questions about. The three main questions I ask are: is the idea genuinely novel? Is it interesting enough? Is it intellectually defensible? The answer must be affirmative in each case before I proceed.

So for the next step, I hunt down the relevant literature by asking ChatGPT, surfing Google Scholar, and asking colleagues who work on similar stuff. That means scanning databases, following citations, and running it by ChatGPT, prompting it to analyze the idea like a referee at a top journal. If I find that someone has already the same article—or something close enough—I will usually shelve the idea. Sometimes, though, it means shifting the focus, narrowing the scope, or locating a gap or tension in the literature. The goal here is to avoid writing something redundant.

Once I know there something new, defensive, and interesting to say, I print out the related research. This is probably the most old-fashioned part of the process. I still prefer to read serious work on paper. I mark it up with pen and highlighter—different colors for different purposes like central arguments, key definitions, clever examples, potential objections. The marginalia are often more important than the original text for my later writing when I consult them for questions, counterarguments, little arrows between sections that should really be read together. By the time I am done, I have an excellent sense of how the idea fits into the broader literature.

Alongside the printed articles, I keep a dedicated notebook. Each paper I read gets its own entry: author, title, main thesis in a sentence or two, and then a set of bullet points keyed to page numbers. In this part of the process, I try to capture what will matter for my argument. Sometimes that means summarizing a section. Sometimes it means writing “this seems wrong because…” and then a few lines of reasoning. The notebook becomes an index of the conversation I am joining, but organized around my project rather than the order in which I happened to discover the sources.

Only after I have done that analog and cognitive legwork do I bring in ChatGPT. At this stage, I treat it as a kind of overcaffeinated colleague who has read a lot, reasons quickly, and is perfectly happy to brainstorm for as long as I like, but whose judgment I do not automatically trust. I feed it the rough abstract, along with summaries or quotations from the key articles I have been working through. Then I ask questions that I would normally ask another philosopher over coffee: how do these pieces fit together? What are the obvious objections I haven’t considered? Are there surprising connections between these arguments that I have overlooked?

The aim here is to use a different kind of approach to shake loose alternatives I might have missed. Sometimes the model tells me things I already know and other times it gives helpful suggestions about framing, distinctions, or other counterarguments I had not fully articulated for myself. I jot those down into the same notebook, flagged as “AI-suggested” so I can keep track of what came from where.

After that, I ask the model to write a rough synthesis of the project on the basis of the abstract and my summaries of the research. Think of this as commissioning a quick, imperfect mini-essay from a smart but hasty graduate student. It tends to get the big picture more or less right, but the details are often off, the nuance is usually thin, and the voice is certainly not mine. That is fine. The point is to see my own materials in a different light to highlight which parts of the project are doing real work and which are just taking up space because I happen to find them interesting.

And then, using the rough abstract, my marked-up articles, the notebook entries, and the synthesis as a kind of mirror, I draft a detailed outline. For a paper-length project, that outline can run to several pages. I break the argument down into sections and subsections such as introduction, motivation, existing views, critique, positive proposal, replies to objections, conclusion. Under each heading, I list the claims to be defended, the sources to be used, and the transitions I need to make explicit. If the AI synthesis suggested a helpful ordering or highlighted a missing step, that gets incorporated here, but in my own words, and only after thinking through it again.

Drafting itself is slower and more solitary. I write on the computer, but I keep the outline and my notebook next to me. The first full draft is where the project becomes recognizably mine. I write until I have something that is complete enough to criticize but still loose enough that I do not feel overly attached to any particular sentence. And then I put it away for a bit to work on something else.

Letting a draft “mature in my brain” is part of the process and allows me to start on another project, while my mind works on the draft in the background. Often I will realize, in the shower or on a walk, that a section belongs earlier, or that an example I used in class would work beautifully here, or that the conclusion needs to be less triumphalist and more modest. I usually jot those insights down as they happen in a notebook or they will be lost forever. And then, when I return to the text after a few days or weeks, I see it with fresher eyes.

Only then do I involve ChatGPT again, and now in a very different role. At this stage, I ask it to behave not like a chatty colleague but like a demanding referee. I paste in the draft and explicitly request a rigorous, critical report: identify unclear passages, gaps in the argument, undefended assumptions, missing literature, distracting tangents, and so on. I encourage it to be uncharitable, and to read the paper like an overworked, skeptical reviewer might. Often, but not always, it will spot real weaknesses in the paper like the need for a distinction, firmer argumentation, or including a source I forgot about.

Crucially, I do not accept these suggestions wholesale. This is where experience and judgment matter. I go through the “referee report” line by line. After a few rounds of rereading and revising, I arrive at what I consider a “shareable draft.” At that stage, I rely on conference presentations or having a colleague look it over, and then eventually I submit it to a journal.

The resulting workflow is neither purely human nor AI-written. It is a hybrid that leans heavily on traditional scholarly virtues like careful reading, slow note-taking, attention to existing work, and a willingness to let ideas ripen over time. The tools—pen, computer, ChatGPT—are simply different tools for extending and scaffolding my limited memory, pattern recognition, self-critique. What matters, in the end, is that the argument I sign my name to is one I understand, endorse, and can defend without any of those tools in the room.

Related: “Ethics announces AI Policy“, “The Ethics of Using AI in Philosophical Research“