Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.

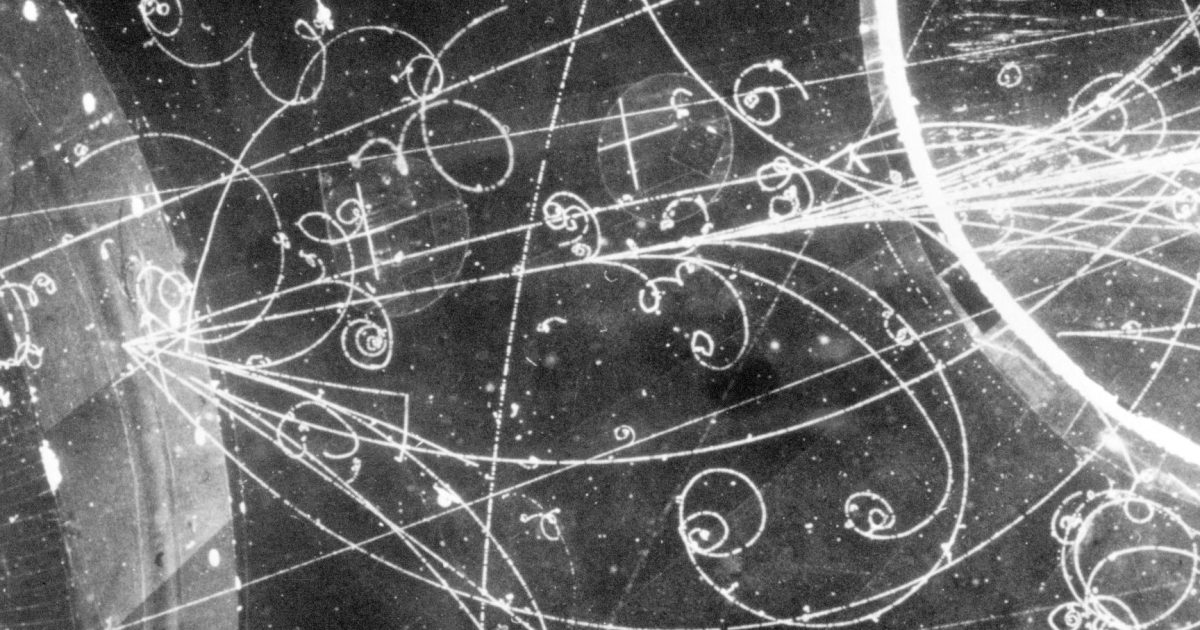

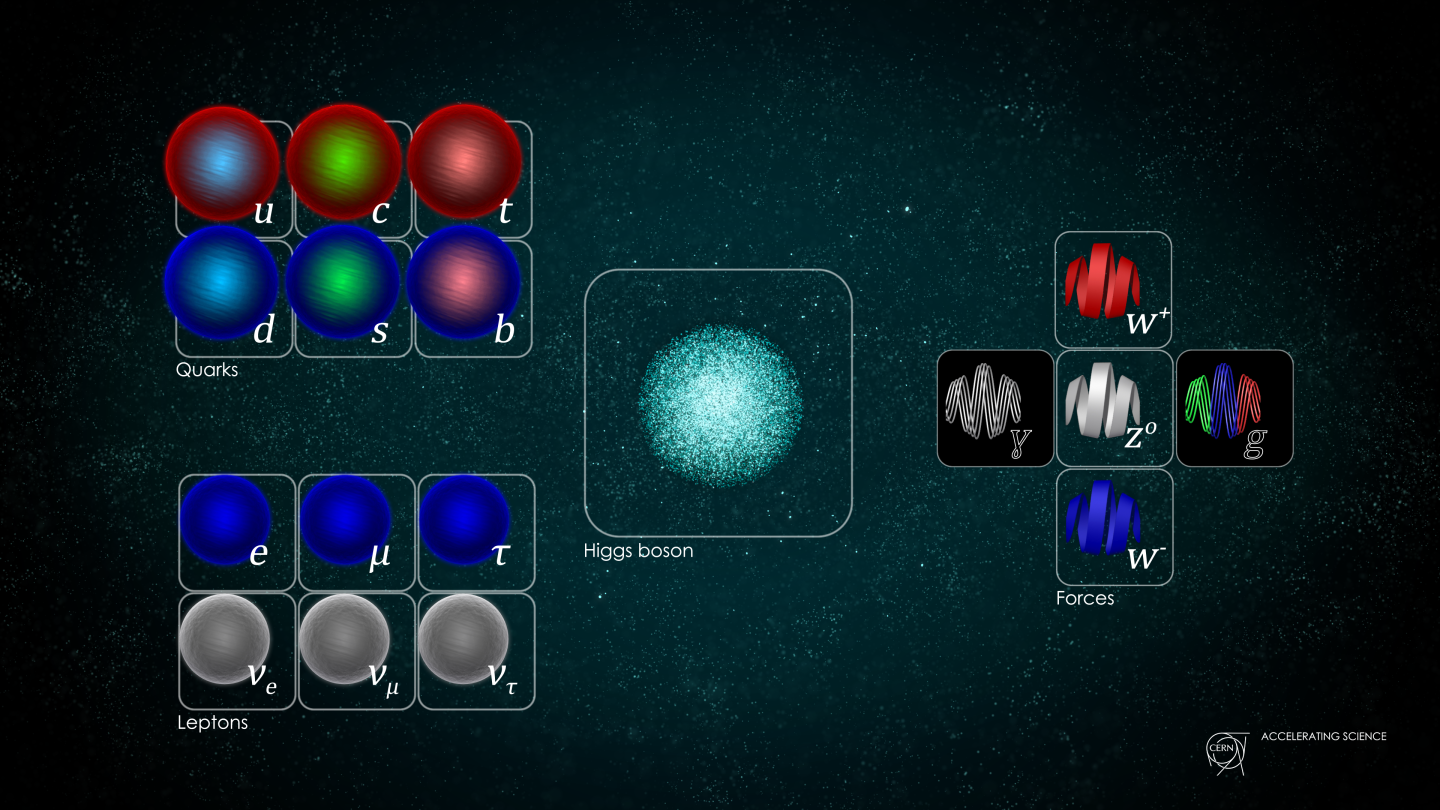

One of the most remarkable facts about the Universe is simply that, over the past couple of centuries, humanity has actually been able to make sense of much of it at a basic, fundamental level. We’ve determined what all of the luminous and light-blocking material, plus radiation, is made of: the normal matter and energy in our Universe that consists of particles within the Standard Model. We’ve discovered black holes and have come to understand how gravity and the expanding Universe works: governed by the laws of Einstein’s General Relativity. And we understand the rules governing how particles interact: through the strong nuclear, weak nuclear, and electromagnetic forces, as dictated by quantum field theory.

While these developments occurred both theoretically as well as observationally and experimentally, this picture has truly been cemented over the last 50 years by a large suite of data: collected from precise particle collider and detector experiments here on Earth, in space, as well as astrophysical and cosmological observations of the grand Universe. The Standard Model of particle physics, as well as the Standard Model of cosmology — rooted in quantum field theory and General Relativity — form the grand foundation of our modern scientific enterprise.

Many have devoted their lives to exploring extensions and alternatives to these standard scenarios, and are (unfortunately) often ridiculed as doing “useless” research. But this research, when done correctly, is anything but useless; it represents the most underappreciated achievements in theoretical physics over the past several decades. Here’s what we’ve learned, and why it’s so valuable.

On the right, the gauge bosons, which mediate the three fundamental quantum forces of our Universe, are illustrated. There is only one photon to mediate the electromagnetic force, there are three bosons mediating the weak force, and eight mediating the strong force. This suggests that the Standard Model is a combination of three groups: U(1), SU(2), and SU(3), whose interactions and particles combine to make up everything known in existence. Despite the success of this picture, many puzzles still remain.

Credit: Daniel Domingues/CERN

When it comes to making sense of the Universe, it’s important to focus our attention on the big picture: the full suite of data and what it both does and doesn’t indicate. Whenever you have a scientific theory, model, or framework that you work within, one of the biggest challenges is to extract testable predictions from it: predictions that are quantitative (i.e., that answer the question of “how much” of an effect occurs), predictions that lead to potentially observable and/or measurable signals, and predictions that differ from the predictions of the other theories, models, or frameworks that are used to describe and predict reality.

We can immediately recognize, historically, that there are many such examples where this is exactly how science advanced. Some notable revolutions included:

Kepler’s theory of elliptical orbits in a heliocentric framework, which matched the observed orbits of the planets, especially that of Mars, better than any other model, including the models of Ptolemy and Copernicus.

Dirac’s theory of the relativistic electron, leading to the successful prediction of positrons (and other forms of antimatter), of the behavior of light and charged particles near the speed of light, the understanding of electron spin, and to an understanding of the fine structure of the hydrogen atom.

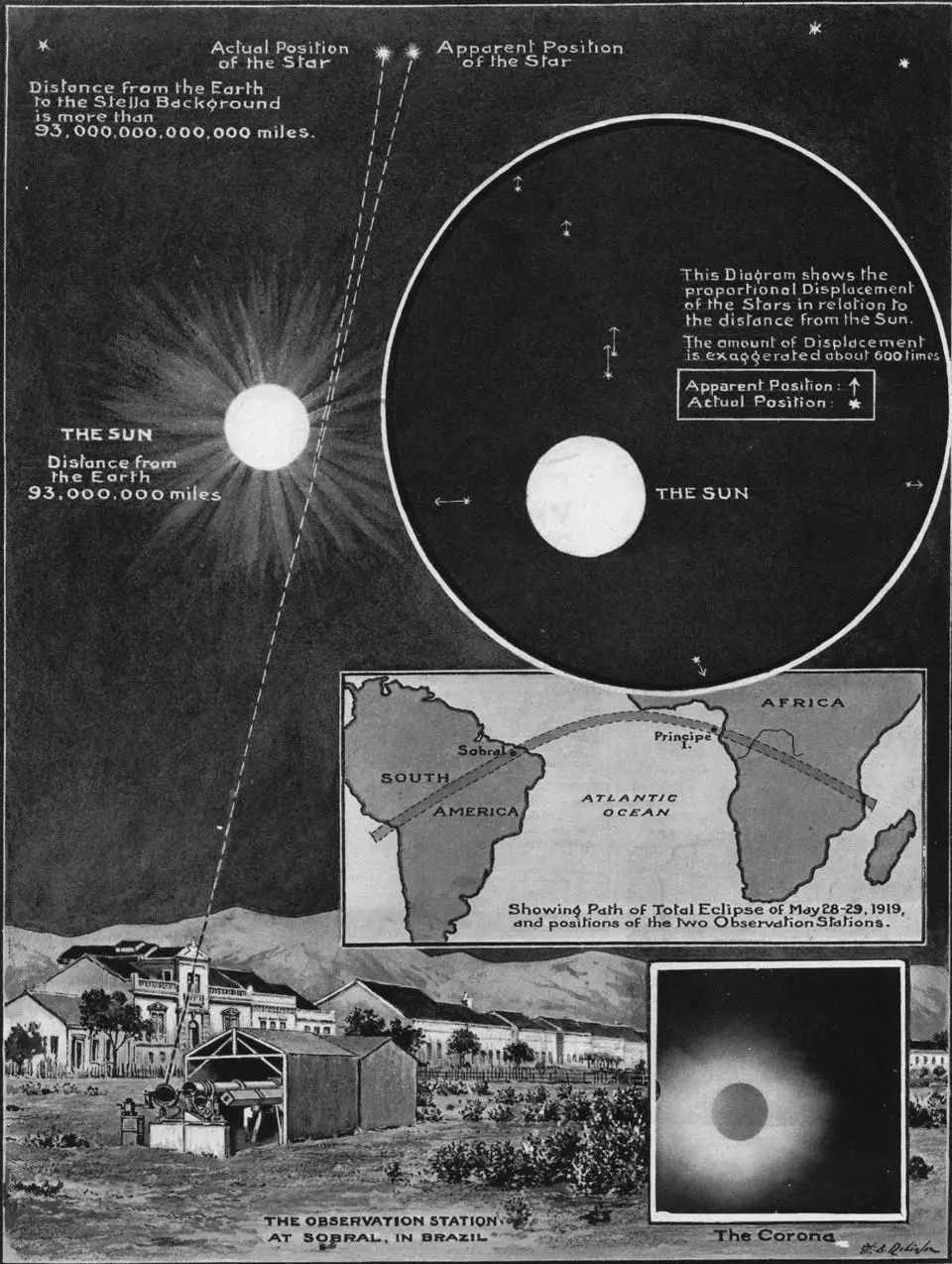

And Einstein’s theory of gravitation — General Relativity — which successfully explained aspects of gravity (like Mercury’s perihelion precession) that Newton’s theory could not, and made several new predictions like the deflection of starlight that passed near a massive object (like the Sun during a solar eclipse) that agreed spectacularly with experiment and observation.

The results of Arthur Eddington’s 1919 expedition, which confirmed and validated the predictions of Einstein’s general relativity, while disagreeing significantly with the alternative (Newtonian) predictions, was the first observational confirmation of Einstein’s new theory of gravity. The amount that starlight was deflected by during a total solar eclipse was a key prediction that was unique to Einstein’s new theory.

Credit: London Illustrated News, 1919

These examples stick out as memorable in many ways for a simple but uncommon reason: because these theoretical developments, which can either be viewed as “alternatives to the then-accepted mainstream” thought of the time or as “extensions to what was generally known at the time,” turned out to lead to predictions that better agreed with our observable, measurable reality than the pre-existing frameworks that they eventually superseded. There were also hints that something was a bit “off” about our pre-existing theories, as:

there were notable discrepancies between the orbits of the planets (especially the ones that we now know have the greatest eccentricities) as observed by Tycho Brahe as compared with the predictions of Ptolemy and Copernicus during the time of Kepler,

there was a lack of agreement between the predictions of the Schrodinger equation under relativistic conditions and observations, and a lack of agreement between the observed fine-structure of the hydrogen atom and the predictions of the Bohr model of the atom in Dirac’s time,

and there was an observed disagreement in Mercury’s orbit as compared with the predictions Newtonian gravity, while alternative explanations (like the existence of a hypothetical “Planet Vulcan” interior to Mercury) lacked direct observational support.

These already-apparent inconsistencies — or from a different perspective, a lack of a perfect agreement with the prevailing theory’s predictions — served as both motivations for the development of a novel, competing, alternative theory to the mainstream, but also served as an immediate sanity check: could the newly proposed theory explain what those longstanding theories couldn’t?

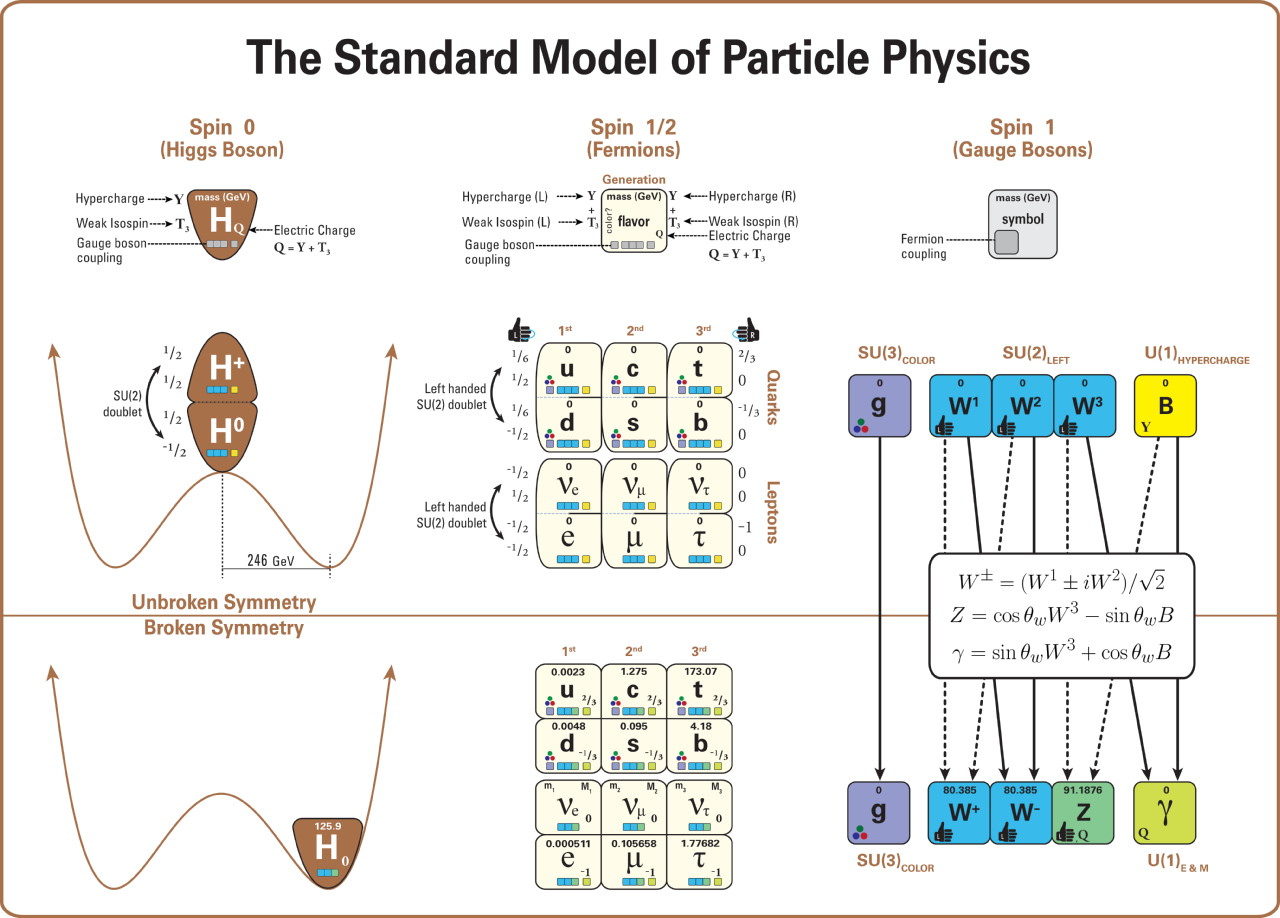

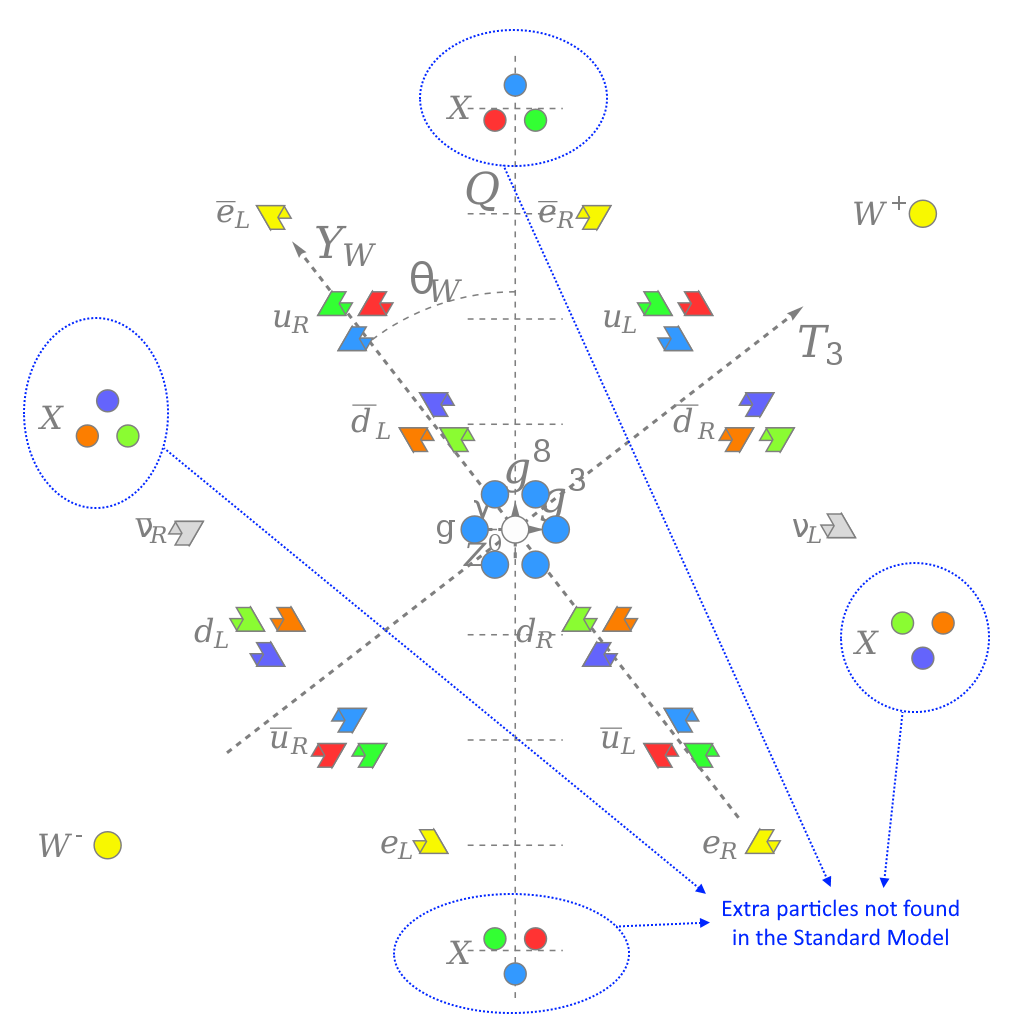

This diagram displays the structure of the Standard Model (in a way that displays the key relationships and patterns more completely, and less misleadingly, than in the more familiar image based on a 4×4 square of particles). In particular, this diagram depicts all of the particles in the Standard Model (including their letter names, masses, spins, handedness, charges, and interactions with the gauge bosons: i.e., with the strong and electroweak forces). It also depicts the role of the Higgs boson, and the structure of electroweak symmetry breaking, indicating how the Higgs vacuum expectation value breaks electroweak symmetry and how the properties of the remaining particles change as a consequence. Neutrino masses remain unexplained.

Credit: Latham Boyle and Mardus/Wikimedia Commons

That’s very analogous to the situation we find ourselves in today, as we seek to understand the nature of reality to the most extreme degree possible. Sure, we have an incredibly successful model of reality right now: the best of all-time. We have a set of force laws that describe all of the interactions we can detect and measure, and a list of cosmic ingredients that describe the contents of our reality exquisitely. We have all sorts of predictions — from both General Relativity and quantum field theory — that are extraordinarily consistent with everything we’ve observed and measured.

And yet, there are all sorts of observed facts about the Universe that our current theories cannot and do not explain. Some of them could simply be, “that’s just how the Universe was born,” and we can foist these mysteries off onto “initial conditions” and ignore them. But there are a great many of them, and they sure are piling up the deeper we look. They include:

the existence of dark matter,

the existence of dark energy,

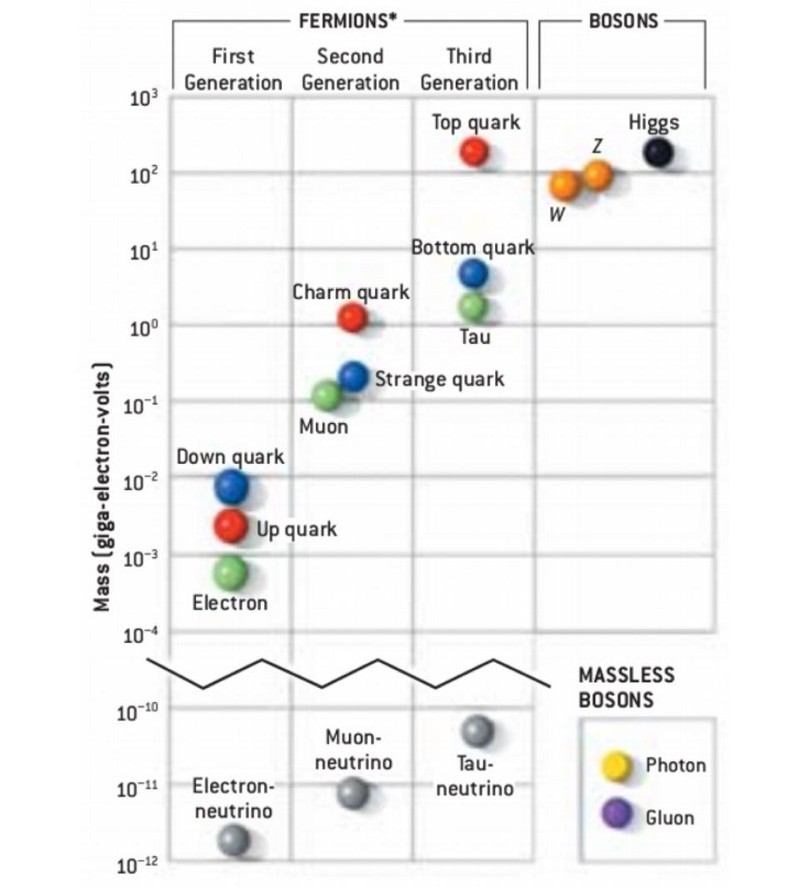

the vastly disparate values of the fundamental constants, including the disparate strengths of the fundamental forces and the disparate masses of the known particles,

the origin of neutrino masses and why there are only left-chiral neutrinos and right-chiral antineutrinos,

the unexplained origin of the matter-antimatter asymmetry,

the Hubble tension, or how different methods of measuring the expanding Universe yield different values,

and a whole lot more. These mysteries, and attempts to resolve them, have led to a great many proposed extensions to the Standard Model.

The rest masses of the fundamental particles in the Universe determine when and under what conditions they can be created, and also relate to how long they can survive after their creation during the hot Big Bang. The more massive a particle is, the less time it can spontaneously be created in the early Universe, and the shorter its lifetime will be. Although we can explain particle masses through a coupling to the Higgs, we have no way of successfully predicting their values; they must be experimentally measured in order to be determined.

Credit: Universe-review

Of course, none of them have cleared the three major hurdles that all proposed new theories must conquer if they are to supersede and replace the prevailing theory as part of our standard, consensus picture of reality. Those three hurdles are as follows.

The new theory must reproduce all of the (often prodigious) successes of the pre-existing, prevailing theory of the day. That means that every one of the changes or extensions that the new theory makes in comparison to the old theory must not conflict with any aspect of the full suite of data that already doesn’t conflict with the prevailing, leading theory that the alternative is seeking to replace.

The new theory must also — and this is often the very reason it was proposed — successfully explain at least one already-observed phenomenon or solve at least one still-unsolved problem that the old theory cannot successfully account for.

And then, assuming both of those earlier hurdles have been cleared, the next step is for the new theory to make novel, testable predictions that differ in some measurable, observable, and testable way from the predictions of the prevailing theory.

Only once all three of these hurdles have been cleared can a new theory be said to supplant, or supersede, the older, prevailing theory. That’s how the foundational picture of reality, often called our current “consensus” position, evolves over time.

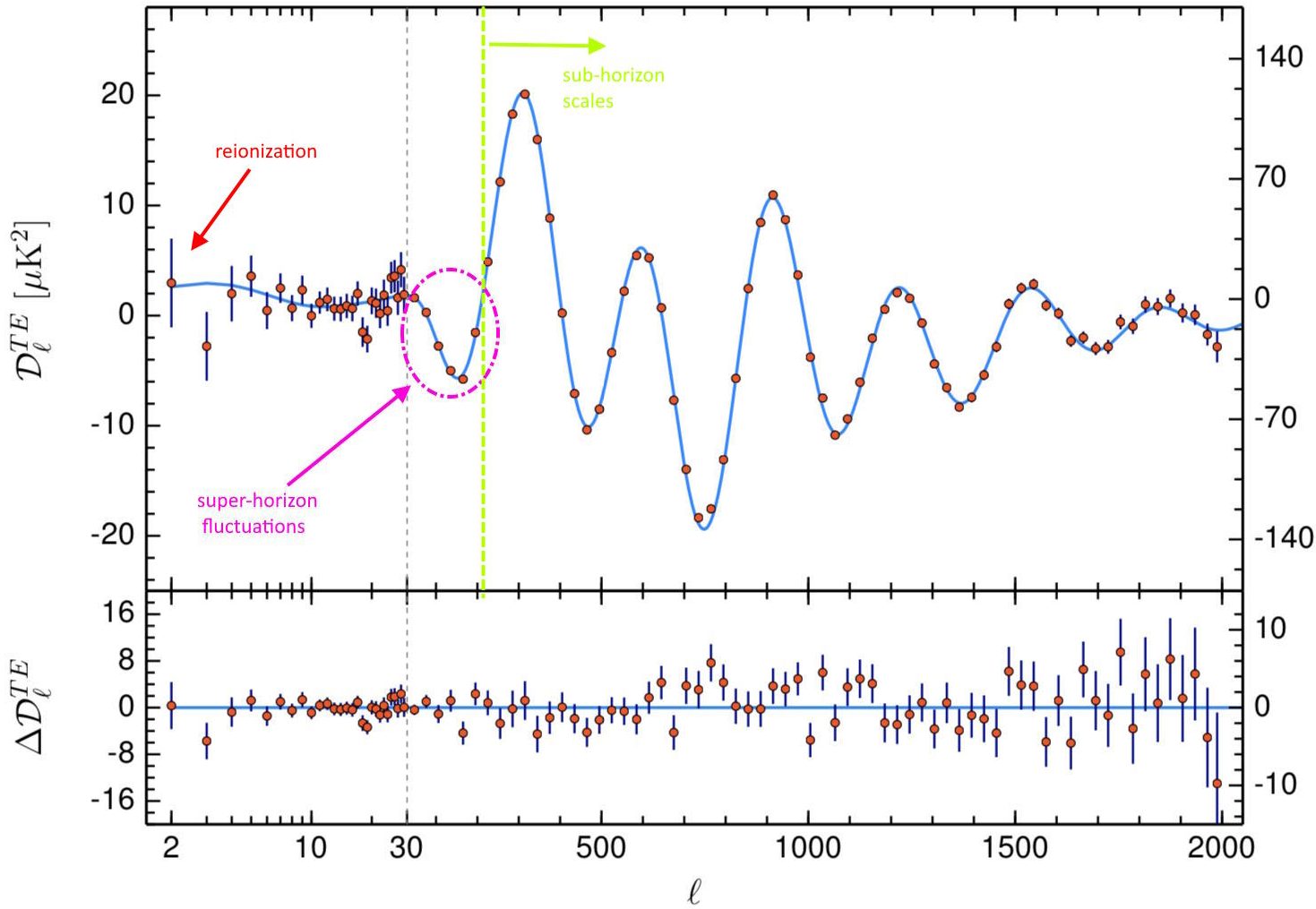

If one wants to investigate the signals within the observable Universe for unambiguous evidence of super-horizon fluctuations, one needs to look at super-horizon scales at the TE cross-correlation spectrum of the CMB. With the final (2018) Planck data now in hand, the evidence is overwhelmingly in favor of their existence, validating an extraordinary prediction of inflation and flying in the face of a prediction that, without inflation, such fluctuations shouldn’t exist.

Credit: ESA and the Planck collaboration; annotations by E. Siegel

This is how the Big Bang came to be our leading picture of reality, and later, how cosmic inflation altered our view of the beginning of the Universe and changed how we viewed the Big Bang: not as the origin of our Universe, but rather as a hot, dense state that emerged in the aftermath of inflation’s end. This is how we came to accept the existence of dark energy, and how we came to model it successfully as a cosmological constant. It’s how we came to understand that our Universe is filled with a species of matter that neither absorbs nor emits light, and that doesn’t interact with normal matter in any directly detectable way except gravitationally: what we presently call dark matter.

It’s only by matching the existing observations and being consistent with the full suite of data that we already have, reproducing every one of the successes of the current theory, succeeding in at least one instance where the current framework does not succeed, and in making robust, testable predictions that differ from the currently accepted theory in a measurable way, that science truly advances.

In the realms of particle physics and cosmology, however, revolutionary successes are exceedingly rare. Far more common are attempts at replacing the existing theory that fail to be borne out by reality: an all-important endeavor that, unfortunately, is largely met with scorn among many influential physicists.

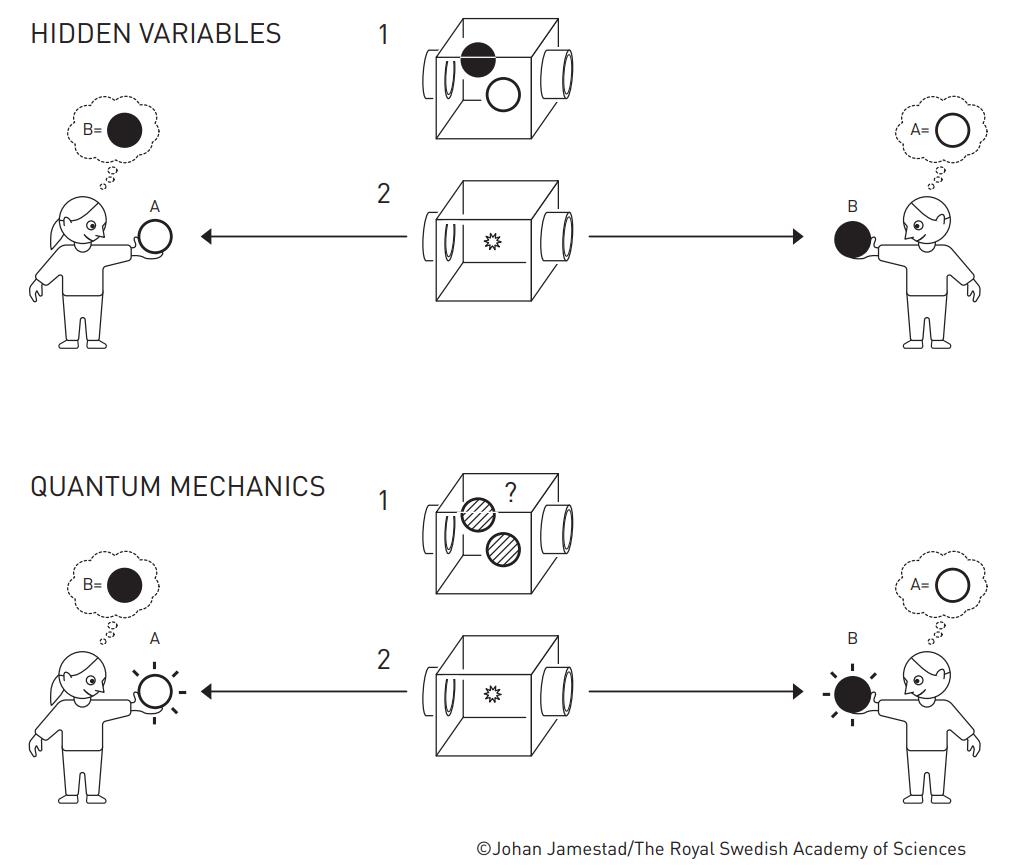

Quantum mechanics’ entangled pairs can be compared to a machine that throws out balls of opposite colors in opposite directions. When Bob catches a ball and sees that it is black, he immediately knows that Alice has caught a white one. In a theory that uses hidden variables, the balls had always contained hidden information about what color to show. However, quantum mechanics says that the balls were gray, or a combination of black and white, until someone looked at them, when one randomly turned white and the other black. Bell inequalities show that there are experiments that can differentiate between these cases. Such experiments have proven that quantum mechanics’ description is correct, and the balls have an indeterminate color until the measurement is made.

Credit: Johan Jamestad/The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

Such scorn is certainly ill-deserved, of course, as it’s the ability to put a novel, promising theory or idea to the test that is the hallmark of good theoretical science. Most people have an incorrect and even a harmful view of science, where it goes something like,

“The first person to stumble upon an idea that ultimately turns out to be correct, even if they wind up getting the right answer due to incorrect reasoning, is the person whose genius should be lauded.”

This thought, despite how common it is, is entirely wrongheaded. The hallmark of a good idea is an idea that:

doesn’t conflict with already-existing data (because if it does, it’s dead-on-arrival),

can explain at least one puzzle that the current theory doesn’t explain (because puzzles are there to be solved, and an idea that solves more puzzles has more predictive power),

and can, in some novel way, be tested and measured against the old theory in a definitive fashion to determine whether the old theory, the new theory, or neither theory is correct.

Attempts to solve the puzzle of the matter-antimatter symmetry, for example, was one of the prime motivations for considering Grand Unified Theories as scenarios worth exploring: where it isn’t just the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces that unify at higher energies, but where the strong nuclear force also joins them at still-greater energies.

The particle content of the hypothetical grand unified group SU(5), which contains the entirety of the Standard Model plus additional particles. In particular, there are a series of (necessarily superheavy) bosons, labeled “X” in this diagram, that contain both properties of quarks and leptons, together, and would cause the proton to be fundamentally unstable. Their absence, and the proton’s observed stability, provide strong evidence against the validity of this theory in a scientific sense.

Credit: Cjean42/Wikimedia Commons

This was a great idea, not because it’s true, but because the idea could be tested. One consequence of grand unification is that — if it’s correct — it mandates the existence of new, super-heavy particles: particles that couple quarks to leptons in a way that goes beyond the normal Standard Model coupling. This enables baryon-number and lepton-number violating interactions, which is wonderful for clearing the second hurdle that a new theory must hurdle: it provides a potential explanation for a hitherto unexplained phenomenon: baryogenesis. However, the true test comes with the third step: a novel prediction that differs from the predictions of the old (Standard Model without grand unification) theory.

That prediction was simple, straightforward, and profound: the proton itself must be fundamentally unstable, with its lifetime dependent on the exact particle content and energy scale of the grand unification scenario under consideration. For example if the straightforward Georgi-Glashow SU(5) unification scenario were correct, the proton should decay with a mean lifetime of around 1030 years.

At present, based on all of the large-scale detectors we’ve built with large amounts of liquid inside (including large numbers of protons), we have yet to observe proton decay, enabling us to set lower limits on the proton’s lifetime that are around a factor of 10,000 longer than that expected decay time; the proton’s lifetime is at least ~1034 years. As a result, we can rule out the original Georgi-Glashow grand unification model, and can place meaningful constraints on other GUT scenarios as well.

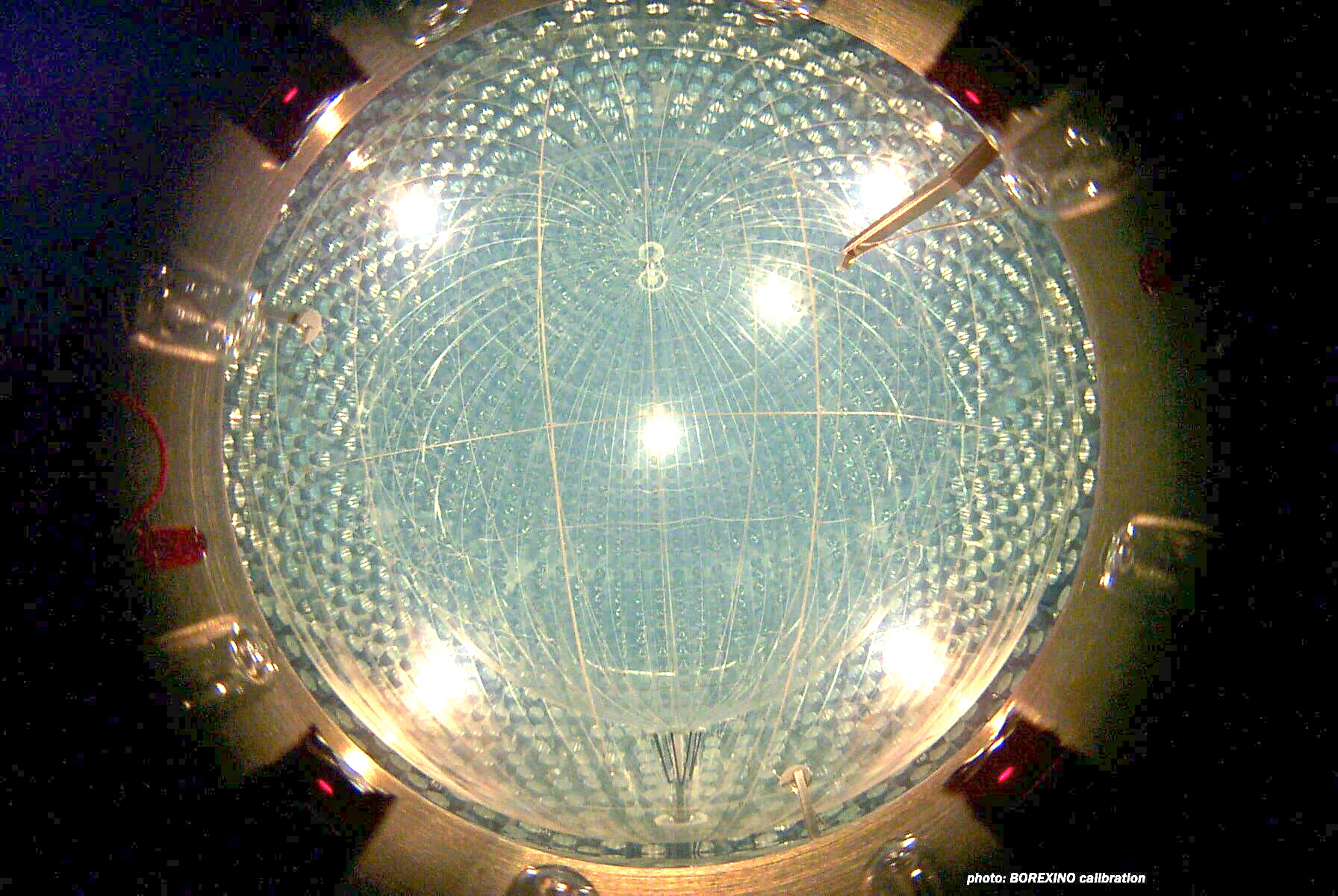

Neutrino detectors, like the one used in the BOREXINO collaboration here, generally have an enormous tank that serves as the target for the experiment, where a neutrino interaction will produce fast-moving charged particles that can then be detected by the surrounding photomultiplier tubes at the ends. These experiments are all sensitive to proton decays as well, and the lack of observed proton decay in BOREXINO, SNOLAB, Kamiokande (and successors), and others have placed very tight constraints on proton decay, as well as very long lifetimes for the proton.

Credit: INFN/Borexino Collaboration

Many other ideas, similarly, can have measurable, testable predictions teased out of them. In electroweak-scale supersymmetry, for example, predictions include:

the existence of flavor-changing neutral currents (which are forbidden in the Standard Model),

the existence of a lightest supersymmetric particle that’s within reach of the LHC (which has not shown up),

and the existence of a spectrum of Higgs bosons, including charged Higgs particles, rather than a single neutral Higgs (whereas the LHC has only revealed one).

This doesn’t eliminate supersymmetry from the realm of possibility just as the non-observation of proton decay doesn’t eliminate the possibility of grand unification but it does rule out and constrain a variety of supersymmetric scenarios.

Similarly, many alternatives to or extensions of General Relativity have been proposed, with some key observable differences including the existence of scalar and/or vector contributions to gravitational effects in addition to the standard tensor-only contributions put forth by Einstein, as in the case of Brans-Dicke gravity or TeVeS, or with a speed of gravity that differs from the speed of light, as in Gauss-Bonnet gravity. The testability of these theories and ideas is of paramount importance, as the observations of the kilonova event GW170817, which saw an electromagnetic signal and a gravitational wave signal arrive within 1.7 seconds of one another from 130-140 million light-years away, have either ruled out or severely constrained these alternatives to Einstein’s General Relativity.

Just hours after the gravitational wave and gamma-ray signals arrived, optical telescopes were able to hone in on the galaxy home to the merger, watching the site of the blast brighten and fade in practically real-time. This 2017 event allowed us to place tremendous constraints on alternative scenarios for both gravitation and electromagnetism, especially considering that the first light signals, in gamma-rays, arrived just 1.7 seconds after the gravitational wave signal completed, across a distance of some ~130,000,000 light-years.

Credit: P. S. Cowperthwaite/E. Berger/DECAm/CTIO

It’s all too easy to point one’s finger at any number of theories (and theorists) and claim that they’re a waste of time, energy, and brain cells, and many do exactly that. But that’s completely unjustified. You can lambast people for clinging to an idea once it’s already been ruled out by the data, but to assert that the point of theoretical physics is to derive how the Universe is misses the point of what physics actually is at its core: an experimental science, not a theoretical endeavor. One of the most important things a theorist can do is to transform the general framework of a novel idea or extension into measurable, testable predictions that can be searched for experimentally or observationally: the science of phenomenology.

Why should a new discovery be guaranteed? Why should one or more favored or fashionable ideas be correct?

The truth is we don’t know until we look, and knowing what we should be looking for, as well as where to look and how to look for it, is an incredible part of the story. From LIGO to the LHC, from neutrino detection experiments to cosmic ray observatories, and from the Event Horizon Telescope to the JWST, we are living in a golden age of high-quality data, capable of testing alternative theories and possible extensions to the Standard Model as never before. Each step we take forward can help us determine not only how nature behaves, but how it doesn’t behave. That’s a tremendous success! Not everyone appreciates it, of course, but it’s probably the most important class of achievement — short of a revolutionary discovery that corroborates a novel theory — that occurs in fundamental physics today.

Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter

Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all.