Scientists have uncovered 97-million-year-old magnetic fossils that hint at a mysterious, extinct marine animal equipped with an internal compass. Researchers from the University of Cambridge and Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin studied these unusually large “magnetofossils” using advanced imaging techniques.

The fossils’ origin remains unknown, but their magnetic properties point to a creature capable of aligning itself with Earth’s magnetic field, possibly one of the first animals to do so.

Magnetic Sensing Decoded By Anatomy

The breakthrough came when scientists identified magnetically aligned crystals inside the find, suggesting the ancient animal may have had the ability to sense Earth’s magnetic field, a form of magnetoreception seen in many modern species, including birds and sea turtles.

These crystals, remnants of biologically formed magnetic minerals, are known as magnetofossils. According to a study, published in Communications earth & environment, the team determined that the structures were too large to have been formed by bacteria, ruling out microbial origins.

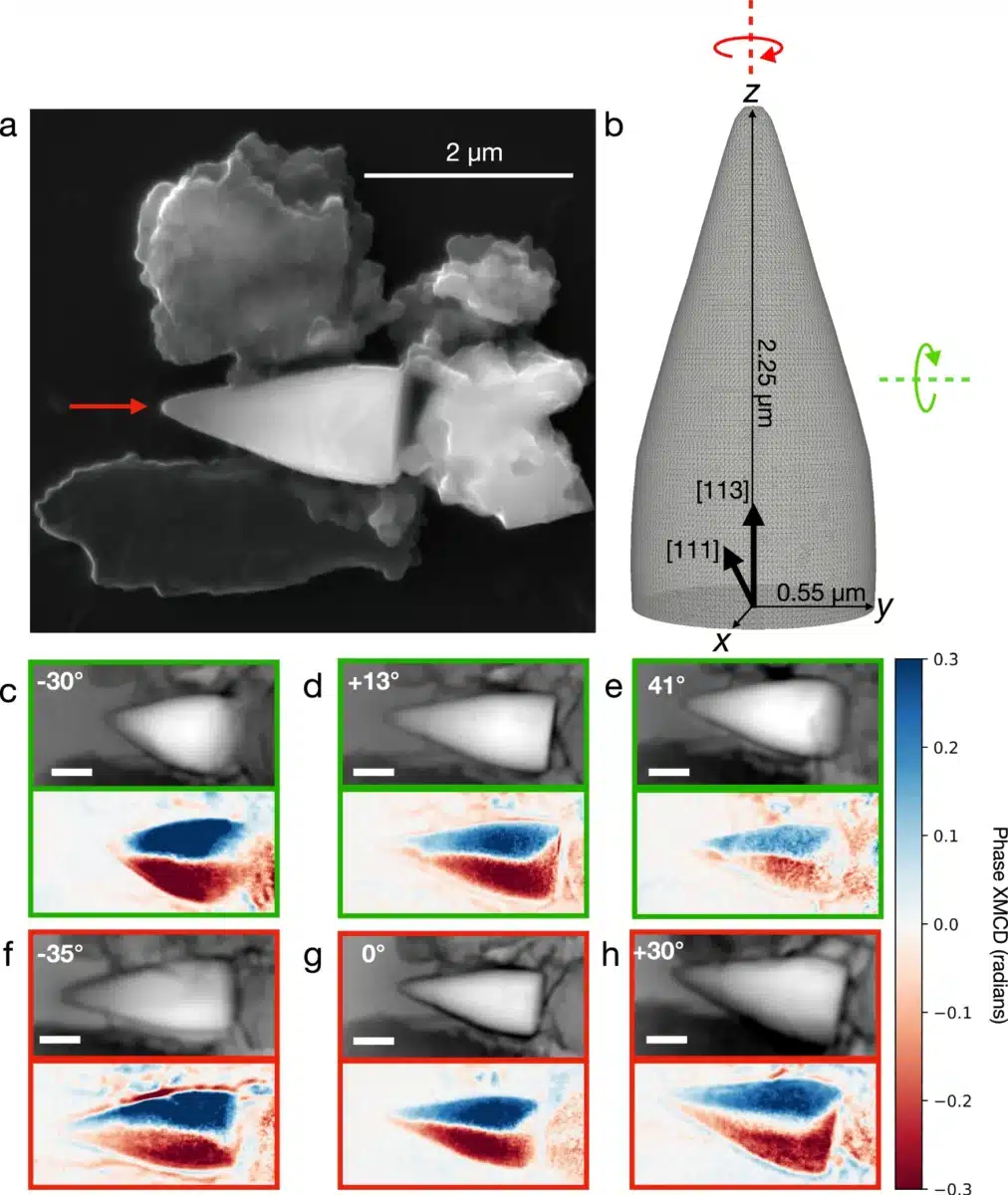

Microscopic and magnetic analysis in 2D of a giant spearhead-shaped magnetofossil. Credit: Nature

Microscopic and magnetic analysis in 2D of a giant spearhead-shaped magnetofossil. Credit: Nature

“This tells us we need to look for a migratory animal that was common enough in the oceans to leave abundant fossil remains,” said Dr. Richard Harrison, co-leader of the research.

The crystals exhibited precisely arranged magnetic moments, tiny magnetic fields generated by spinning electrons, that strongly resemble those found in present-day species with magnetic sensing abilities.

Hidden Ancient Complexity Uncovered

Traditional X-ray methods failed to visualize the interior of the remains, so the research team used a newly developed method called magnetic tomography. The technique, created by Dr. Claire Donnelly of the Max Planck Institute, allowed scientists to image the fossilized structure’ internal magnetic configuration in three dimensions.

“It’s fantastic to see our method being used for the first time to study natural samples,” said Jeffrey Neethirajan, a doctoral student in Donnelly’s lab

The scans were conducted at the Diamond Light Source in Oxford, a facility specializing in synchrotron X-ray imaging. The success of this approach not only confirmed the fossils’ magnetic architecture but also demonstrated that such detailed internal mapping is possible on ancient biological materials.

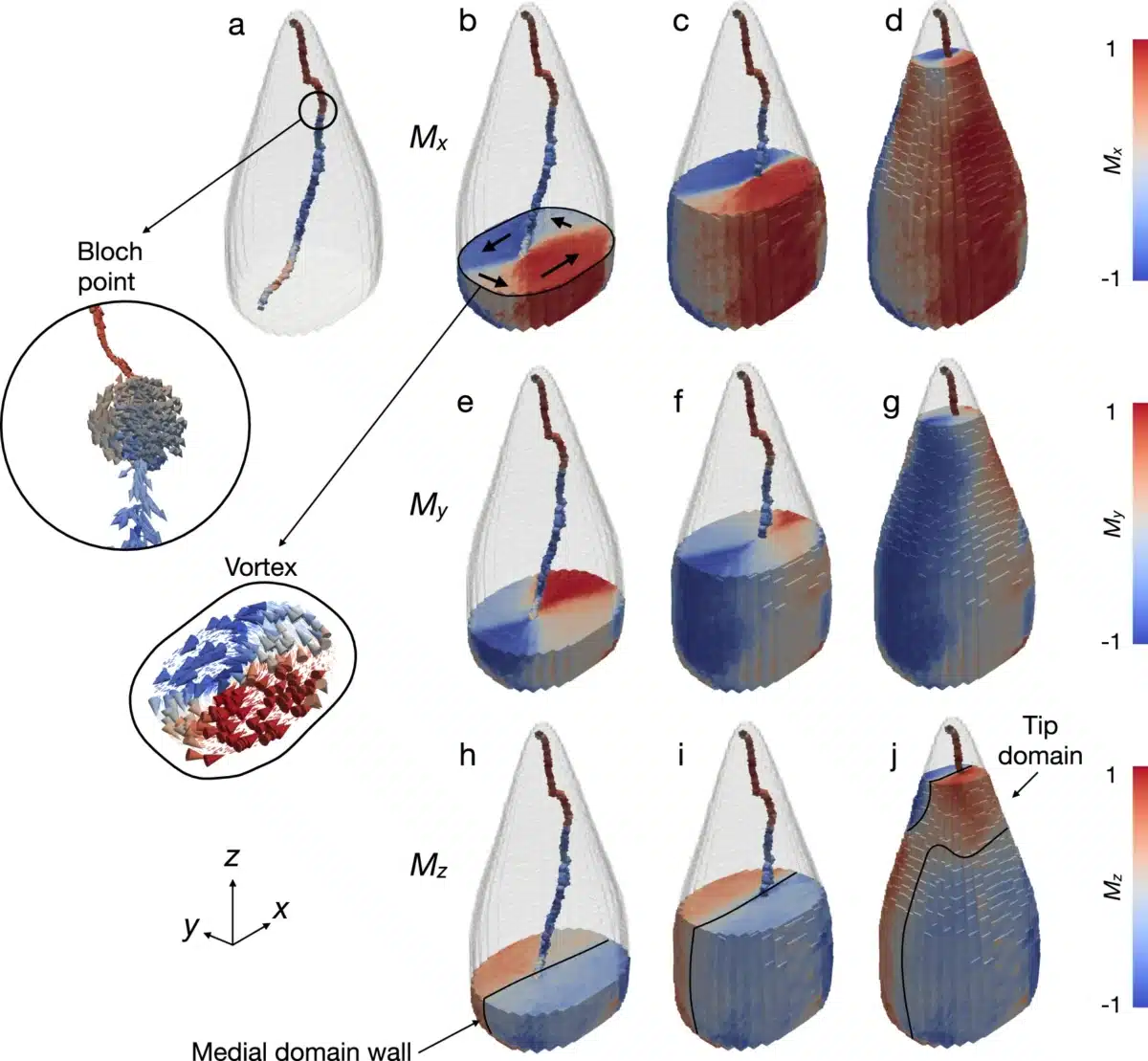

Three-dimensional magnetic vector mapping of a giant spearhead-shaped magnetofossil. Credit: Nature

Three-dimensional magnetic vector mapping of a giant spearhead-shaped magnetofossil. Credit: Nature

An Extinct Navigator Still Unidentified

Although the team has yet to identify the creature that produced the fossils, its biological sophistication is evident. The size and organization of the magnetic structures suggest a multicellular marine animal, potentially one capable of long-distance navigation. Dr. Harrison speculated that eels, which evolved around the same time and are known for global migration, could be possible candidates, but emphasized that no link has yet been established.

“Giant magnetofossils mark a key step in tracing how animals evolved basic bacterial magnetoreception into highly-specialized, GPS-like navigation systems,” he explained.

As reported, Harrison noted that these “giant magnetofossils” represent a key point in understanding how magnetoreception evolved from primitive bacterial systems into complex navigation tools in larger animals. The findings suggest that magnetically guided migration has much deeper evolutionary roots than previously thought.