Gold has long been regarded as one of the most chemically inert elements, a stable constant in both scientific instrumentation and commercial applications. In high-pressure laboratories, it serves a specific role: a passive material that resists reaction, maintains its structural integrity, and reliably transmits energy. This reputation has made it a preferred choice in experiments that probe extreme states of matter, where the reactivity of other elements must be minimized to isolate target phenomena.

Yet the physical environments common across much of the universe do not align with conditions on Earth. Inside the cores of gas giants, at the heart of stars, and within fusion reactors, pressure and temperature exceed terrestrial benchmarks by several orders of magnitude. Under these extremes, assumptions about material behavior begin to shift. Previously unreactive elements form unexpected compounds; states of matter emerge that have no analog at standard temperature and pressure. These departures are not anomalies, they are systemic realities in high-energy physics and planetary modeling.

In late 2025, researchers observed gold forming a stable compound with hydrogen, gold hydride, under laboratory conditions replicating the interior of large planets. The reaction occurred at pressures above 40 gigapascals and temperatures exceeding 2,200 kelvin, and it represents the first confirmed solid-state compound of gold and hydrogen.

Inert No More: Gold’s Transformation Under Planetary Conditions

The synthesis of gold hydride was first reported in Angewandte Chemie in late 2025. The compound, identified as Au₂Hx, formed at a pressure threshold of 40 GPa and grew increasingly hydrogen-rich up to 80 GPa. Hydrogen atoms, normally difficult to detect via X-ray diffraction due to low scattering cross-section, were tracked indirectly through changes in gold’s lattice structure.

The experiment utilized the European XFEL, a high-repetition-rate X-ray free-electron laser near Hamburg, to deliver intense pulses that enabled localized heating within a diamond anvil cell. Gold foil, selected for its assumed inertness, served as a thermal medium. The hydrogen source originated from decomposed hydrocarbons embedded in the experimental sample.

Researchers found that under these extreme conditions, hydrogen entered a superionic state, moving freely within a solid gold lattice. The resulting material adopted a hexagonal structure not previously associated with gold. On cooling to ambient conditions, the compound reverted to its original face-centered cubic form, confirming the phase transition was reversible.

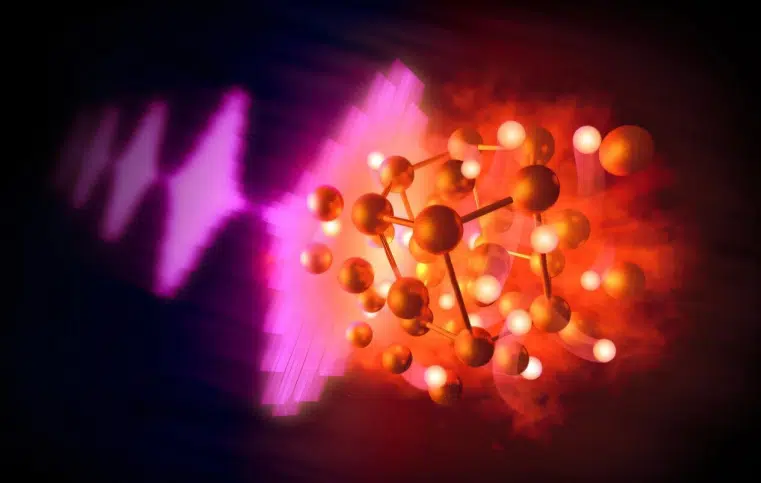

Illustration of intense pulses from an X-ray free-electron laser (left) heating compressed samples of hydrocarbons to extreme conditions, resulting in the reaction of gold and hydrogen to form gold hydride (center). The gold atoms, shown in gold, are fixed in a hexagonal crystal lattice through which the hydrogen, shown in white, diffuses freely in a “superionic” state. Credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Illustration of intense pulses from an X-ray free-electron laser (left) heating compressed samples of hydrocarbons to extreme conditions, resulting in the reaction of gold and hydrogen to form gold hydride (center). The gold atoms, shown in gold, are fixed in a hexagonal crystal lattice through which the hydrogen, shown in white, diffuses freely in a “superionic” state. Credit: Greg Stewart/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

“This represents the first confirmed binary solid compound of gold and hydrogen,” said lead author Mungo Frost of the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, which contributed key instrumentation and data interpretation. The team included collaborators from multiple European and U.S. research institutions focused on high-energy-density science and planetary modeling.

Modeling, Instrumentation, and Theoretical Gaps

The discovery raises complications for researchers who routinely rely on gold as a chemically passive element in high-pressure experiments. Its unexpected reactivity necessitates a re-evaluation of previous results where gold’s chemical stability was a built-in assumption. Experiments involving high-pressure phase transitions, shock compression, or fusion diagnostics may need to reanalyze past findings for unintended interactions.

Instrumentation is also a factor. The European XFEL’s beamlines, designed for femtosecond-resolution studies of matter under stress, were critical in detecting the structural changes linked to hydrogen incorporation. With pressure levels reaching those of Earth’s lower mantle, the experimental conditions aligned with studies in planetary formation and fusion confinement research, creating cross-disciplinary relevance.

Theoretical models also require revision. Ab initio molecular dynamics simulations revealed that hydrogen diffuses rapidly through the gold lattice, behaving more like a fluid than a gas. This behavior parallels findings in superionic water and metallic hydrogen compounds, materials increasingly studied in the context of giant planets and high-pressure ice phases.

While similar hydrides have been reported in other metals, such as platinum and palladium, the formation of a gold-based hydride expands the known boundary conditions of noble metal chemistry. This development complicates existing models of planetary cores where hydrogen may be incorporated into metal-rich interiors at extreme densities.

Open Research Priorities as Inert Elements Fall Under Review

These findings intersect with current efforts to simulate the structure and transport properties of hydrogen-metal mixtures under deep planetary conditions. A 2024 study in JGR Planets investigated molten iron hydrides at high pressure, showing that increased hydrogen content reduces viscosity and enhances atomic diffusion, critical parameters for modeling convective behavior in planetary interiors.

In fusion science, gold hydride introduces a potential calibration material for modeling hydrogen under confinement. Fusion devices that aim to replicate stellar processes rely on accurate simulations of hydrogen’s phase transitions at high density. Gold’s structural response to hydrogen absorption provides a measurable system to benchmark these models and assess non-ideal plasma conditions.

Researchers are now exploring whether gold hydride exhibits any properties of technological relevance beyond its scientific novelty. Other metal hydrides have demonstrated superconductivity or electrochemical activity under pressure. Although speculative, the gold-hydrogen system may offer similar characteristics at specific thermodynamic thresholds, prompting new lines of inquiry in high-pressure condensed matter physics.