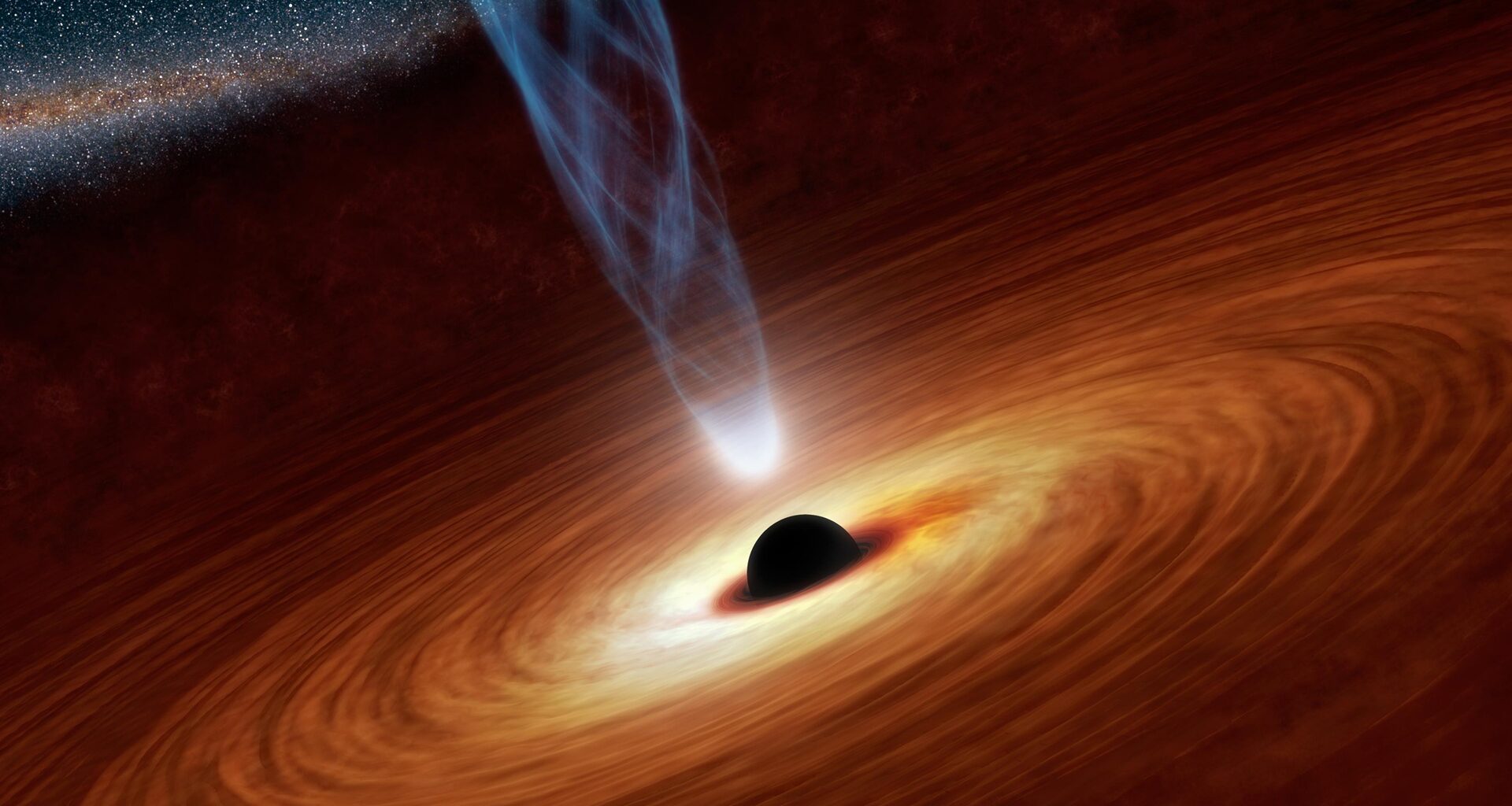

Japanese astronomers have discovered an extraordinary supermassive black hole in the early universe that is growing at a nearly impossible pace, while producing intense X-ray and radio emissions simultaneously.

The find, made by scientists at Waseda University and Tohoku University in Japan, challenges long-standing theories and suggests that the key physical processes operating in the young cosmos remain poorly understood.

The team spotted the distant quasar, an actively feeding supermassive black hole, using observations from the Subaru Telescope. It existed when the universe was less than 1.5 billion years old.

It is undergoing extremely rapid accretion while simultaneously shining brightly in X-rays and producing strong radio emission from a jet. These are features that many theoretical models do not expect to coexist.

The Eddington limit

Supermassive black holes, which can contain millions to billions of times the mass of the sun, sit in the centers of most galaxies. They grow by pulling in surrounding gas, typically hydrogen and helium, from their host galaxies.

As gas spirals inward, it can power a compact region of hot plasma known as a corona which emits X-rays. Additionally, some supermassive black holes form a jet of outflowing material that emits strongly at radio wavelengths.

However, if gas falls toward a supermassive black hole too quickly, radiation from the gas starts to push back on the material flowing behind it. It causes the flow to slow down.

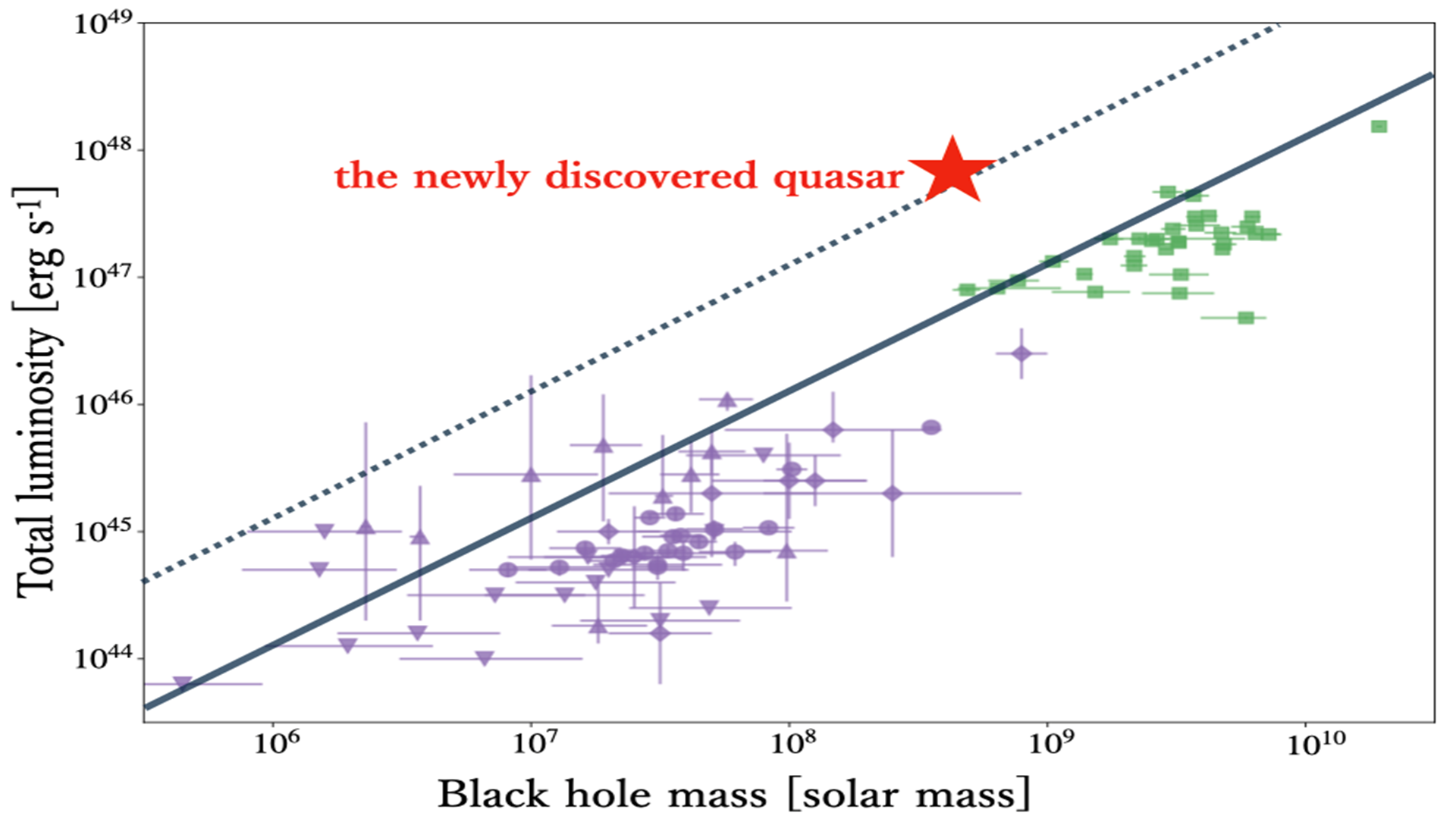

Quasar luminosity versus black hole mass for the newly discovered object (red star) and known quasars.

Quasar luminosity versus black hole mass for the newly discovered object (red star) and known quasars.

Credit: National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ)

This sets a self-regulating Eddington limit, which is, in essence, a speed limit on how fast gas can flow in. However, even the Eddington limit is broken sometimes, enabling rapid mass build-up over short cosmic timescales.

In rare cases, black holes are thought to temporarily exceed this limit through so-called super-Eddington accretion, allowing them to gain mass rapidly over short cosmic timescales. However, such extreme growth is usually expected to suppress high-energy radiation and weaken jet activity.

Breaking physics laws

To discover whether such extreme growth happens in the early universe, the team used Subaru’s near-infrared spectrograph MOIRCS. They measured the motion of gas near the black hole and estimated its mass from the Mg II emission line.

X-ray data revealed that the black hole is accreting material at roughly 13 times the Eddington limit, placing it among the fastest-growing black holes known at this mass scale.

“This discovery may bring us closer to understanding how supermassive black holes formed so quickly in the early Universe,” Sakiko Obuchi, PhD, a researcher at Waseda University and lead author of the study pointed out.

In addition, the researchers observed that the object shines brightly in X-rays and emits strong radio waves. This was clear evidence of an active hot corona and a powerful jet. Current models of super-Eddington accretion predict that these features should be weakened or absent when growth becomes so extreme.

“We want to investigate what powers the unusually strong X-ray and radio emissions, and whether similar objects have been hiding in survey data,” Waseda concluded in a press release.

The team believes the quasar is caught in a short-lived transition, in which a rapid inflow of gas pushed it beyond the Eddington limit, while its X-ray corona and radio jet persisted briefly before fading.

If confirmed, the observation could offer a snapshot of time-variable black hole growth in the early universe, which is difficult to capture observationally. It may also help explain rapid galaxy growth, as powerful jets can shape star formation during extreme black hole growth.

The study has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.