When the remnants of a tropical storm dumped 15 inches of rain on a corner of Texas earlier this month, causing flash floods which claimed 138 lives, it was not long before conspiracy theories began circulating that it was a manmade catastrophe.

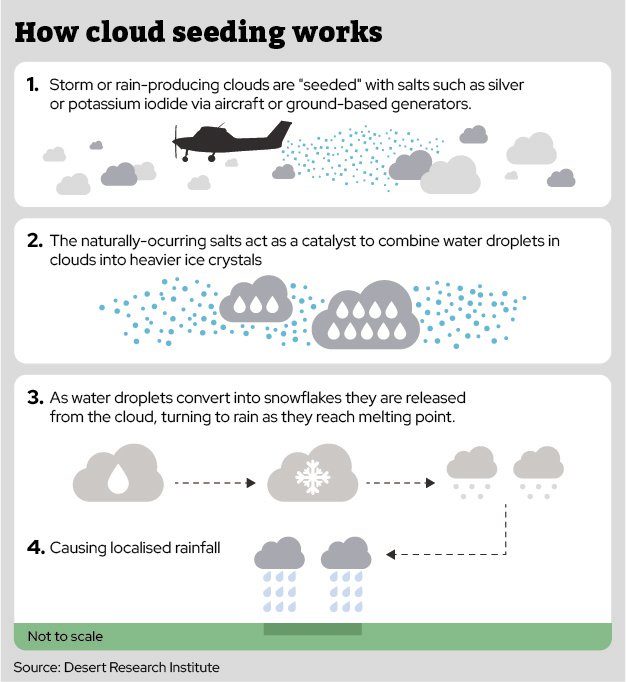

Rainmaker, a California company which specialises in “cloud seeding” technology using chemical compounds sprayed from an aircraft to induce localised rainfall, found itself the target of online finger pointing after one of its flights had dispersed 70g of silver iodide some 100 miles from the site of the disaster a full two days before it happened.

Just as happened last year when cloud seeding was implicated in deluges which closed Dubai International Airport, scientists and meteorologists have since queued up to testify as to the impossibility of a technique in use for several decades having had anything to do with the Texas tragedy.

The Rainmaker flight induced a brief drizzle of 0.5cm of precipitation from two clouds over a scattering of parched farms. By contrast, the tail of the tropical storm which turned the Guadalupe River in Texas’s Kerr County into a lethal torrent on 4 July generated some five trillion litres of water – a feat of which only nature is capable.

“Man should not be playing God with our weather”

But what was different about the response to the Texas disaster was not so much its ability to spark outlandish theories about climate manipulation, but the profile of the individuals promulgating them.

Until recently, the idea that phenomena ranging from extreme weather events to the vapour trails behind aircraft are evidence of nefarious human activity has been the currency of fringe, often far-right, online agitators.

Instead, conspiracy theories about “weather manipulation” and “geoengineering” – the emerging branch of science which seeks to use technical innovations to mitigate global warming – are steadily worming their way onto the agendas of the holders of prominent elected offices.

Marjorie Taylor Greene, the Republican Congresswoman and one of Donald Trump’s staunchest allies in Washington, this week unveiled a proposed law which would prohibit “all weather manipulation, including geoengineering [and] cloud seeding” upon pain of a five-year jail term. Writing on X, Greene said: “We must get this bill passed. Man should not be playing God with our weather!”

She is not alone. At the last count, more than a dozen American states had passed or are considering similar laws banning or restricting the same or similar activities. Among them is Florida, where the state’s senior law officer this month wrote to all airports warning them of $100,000 (£70,000) fines for any use of aircraft to change the climate by injecting chemicals into the atmosphere.

Britain’s £60m scheme to explore holding back climate change

The willingness of senior MAGA politicians to add an already vexed area of climate science to their armoury of polarising issues is the latest complicating factor for British academics and researchers, supported by nearly £60m of Government money, who are at the frontline of efforts to establish whether geoengineering could or should be applied to mitigating climate change.

This experimental work is vastly different from cloud seeding, which governments from China to Saudi Arabia have spent heavily on in recent years with mixed results.

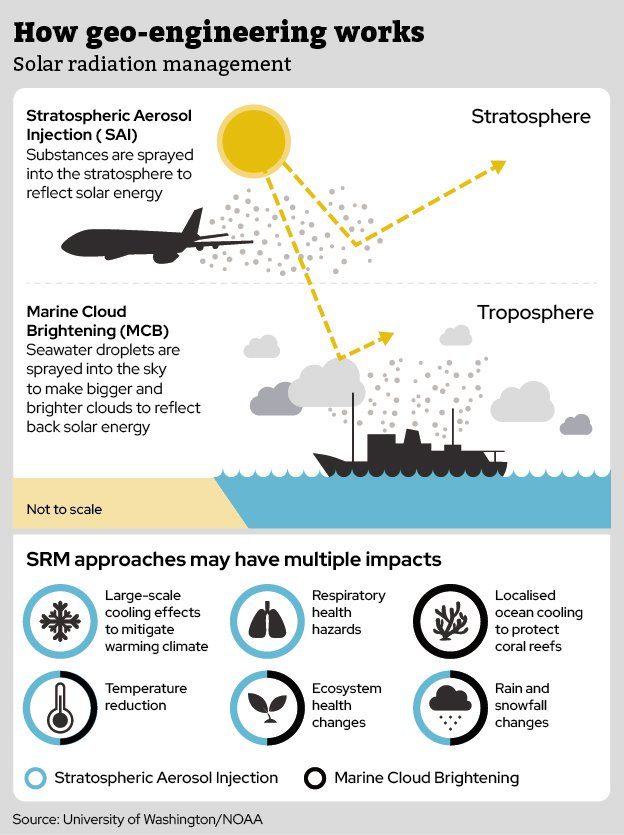

But UK scientists involved in solar geoengineering, which could eventually be deployed to lessen the impact of the sun’s rays in locations from threatened habitats such as the Great Barrier Reef or the polar ice cap to entire regions, are concerned that their separate research is being increasingly conflated with other weather modification activities to the extent that public opinion could be turned against work they consider to be vital.

One UK academic involved in the research told The i Paper this week that attempts to explore geoengineering are at risk of being derailed by being rendered “a political football”.

The projects, and similar programmes in America and beyond, are born from an aspiration to deploy humanity’s engineering nous effectively as a stop-gap to shield the planet from the worst extremes of global warming while the main solution to climate change – the drastic reduction of carbon emissions – is put into place.

As early as next year, British-led teams are scheduled begin “controlled, small-scale outdoor experiments” to explore technologies such as winter thickening of Arctic ice and so-called Solar Radiation Management (SRM), which looks at reflecting some of the sun’s energy back into space.

The solar geoengineering techniques include marine cloud brightening (MCB), which involves spraying seawater droplets of a particular size to increase the reflectivity of clouds, and stratospheric aerosols – the use of mineral dusts to reflect amounts of solar energy back into space.

At least three of the experiments are due to take place in the UK, with effects which organisers insist are fully reversible or last less than 24 hours.

The projects have been made possible as part of a £56m programme of research into “climate cooling” co-ordinated by the UK’s Advanced Research and Innovation Agency (ARIA), the publicly-funded body established in 2023 to fund “high risk, high reward” science and technology projects.

One scientist, who declined to be named, said: “The work being funded by ARIA is important science. It will start to give us the answers to crucial questions where we are currently in the dark such as the viability, safety and potential of these technologies.

“The problem is this growing desire to use climate science as a political football. It’s far easier for some to blame something like the Texas floods on a tangible event like cloud seeding than the unpredictability of global warming.

“My concern is that the science will be drowned out by politicians who see more advantage in raising demons in the public mind than answering questions which could help humanity face its greatest threat.”

“Perhaps solar geoengineering is the price we must pay”

The work being undertaken is a menu of largely untried but, according to their proponents, potentially highly effective routes to temporarily lower surface temperatures on a local, regional or even planetary basis.

Among the techniques being considered under ARIA’s programme, which makes the UK one of the world’s biggest funders of geoengineering research, is a £342,000 desk-based study to assess the feasibility of a putting a solar reflector into space to intercept some of the sun’s energy before it reaches Earth.

The probing of such “highly-speculative” techniques sits alongside more advanced work, including the five experiments in areas such as marine cloud brightening with sea sprays and electric charges, and testing the effectiveness of aerosols by sending small samples of mineral dust attached to weather balloons into the stratosphere. None of the projects involve cloud seeding.

One experiment, being led by a team from Cambridge University, is using a grant of £10m to explore reinforcing the Arctic’s fast-shrinking ice cover by using robotic apparatus to pump sea water to the surface to thicken ice and prolong its presence during the summer months.

Aware of the unproven nature of these technologies and their potential for unintended consequences, both the scientists involved and ARIA itself are at pains to underline the temporary and modest scale of the work.

In the case of the mineral dust experiment due to be conducted in the US and the UK, the few milligrams of material will not even be released into the atmosphere and will instead be carried on trays which will return the dust to the ground for analysis.

Professor Mark Symes, director of ARIA Exploring Climate Cooling project, told The i Paper that the scheme was needed to fill a “critical evidence gap” with experiments which would be undertaken transparently and in consultation with host communities.

He said: “The only sustainable way to mitigate climate change is through decarbonisation. However, there is also a growing global interest in earth cooling approaches, which might act on faster timescales than decarbonisation. The level of interest has outpaced the availability of robust real-world data on the feasibility and potential impacts of proposed earth cooling approaches.”

Indeed, there is a clarity among proponents of geoengineering that doing nothing is not an option.

Robert Chris, a geoengineering expert who works with Cambridge University and the Open University, says those involved in the field openly acknowledge the idea of deliberately altering the atmosphere is “fraught with ethical, geopolitical and practical problems”.

Writing on The Conversation academic platform last month, he added: “It is and always has been a crazy idea. However, many consider the failure to control carbon emissions means not intervening in this way is an even crazier idea… Perhaps solar geoengineering is the price we must pay for our wholly inadequate climate change response to date.”

David Keith, professor of geophysical sciences at the University Chicago, who is widely regarded as one of the lead proponents of geoengineering, said he applauded the UK Government’s investment in the area, saying it appeared to be nudging other countries towards similar projects.

He added that while there is some evidence of public support for solar geoengineering trials – one survey published this month showed 57 per cent of people would support small-scale trials of aerosol dispersal – it would be the decision of policy makers to pursue the technology if proven.

He told The i Paper: “I make a sharp distinction between the climate science and the question of whether, as a matter of public policy, it may make sense to implement some climate engineering technologies. I think it is manifestly not the job of science to win over public opinion on anything but the general idea that high quality science is a public good.”

Opposition to weather modification stretches from social media to academia

It is, however, not just from the fringes of the internet or in the halls of Congress that advocates of geoengineering face questions about the viability of their work.

In 2022, some 575 leading academics, including 162 based in the UK, signed an open letter calling for a “no-use” agreement overseen by the United Nations to “prevent the normalisation of solar geoengineering as a climate policy option”, not least because they said it risked distracting attention from the main goal of slashing carbon emissions.

The signatories argued that geoengineering faced insurmountable challenges, including that the risks of interfering with the amount of solar energy reaching the planet can never be fully known and result in uncertainties about “weather patterns, agriculture, and provision of basic needs of food and water”.

The result is that, doubtless uncomfortably for the ranks of professors and researchers who signed up to support the stance, there is now significant overlap between the carefully-argued ministrations of academics opposed to solar geoengineering and the goals of the denizens of the internet fond of posting pictures of cloud formations alongside hashtags such as “#geoengineering” or “#climatescam”.

When The i Paper this week asked UK signatories of the 2022 letter about finding themselves in one sense sharing a common goal with politicians such as Marjorie Taylor Greene, one replied: “I have seen nothing which changes my mind as non-viability of solar geoengineering and I have no control over who shares that view.”

Joanna Haigh, one of Britain’s foremost climate change experts and emeritus professor of atmospheric physics, underlined that geoengineering can do little to stop climate change, arguing that the ARIA funding could have been spent elsewhere.

She said: “Solar radiation modification cannot address the fundamental problems in climate being caused by human-produced greenhouse gases. It is a large amount of money… which would be more usefully spent on less fanciful projects such as home insulation.”

In the meantime, geoengineering scientists are cautiously continuing their work, including experiments which ARIA insists are “not designed to block or dim the sun, or carry out large-scale climate modification”. As the UK researcher put it: “The shadow in this area is coming from politics, not science.”