In the U.S., it’s real, but broadly mischaracterized.

It started in July 2024, during the presidential campaign. Donald Trump declared a crisis in energy prices, and promised he would bring down the price of electricity by 50% within 12 months 🙄. Kamala Harris, quickly followed suit, not wanting to appear insensitive to this major stressor among low and middle income families.

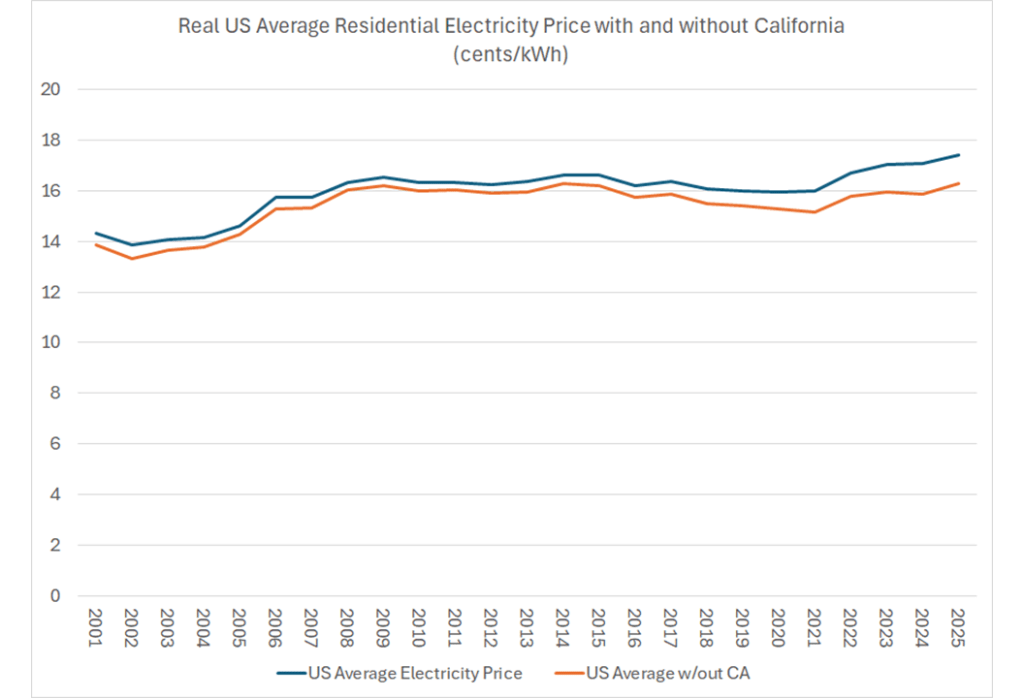

But nationally, electricity prices in 2024 were doing about what other prices were doing. As the figure below shows, the average US residential electricity price was climbing roughly at the rate of inflation. Thus, the real (inflation-adjusted) price had been almost flat for nearly two decades. In fact, if you took California out of the average – with its wildfire management costs and high subsidies for rooftop solar paid by other customers – the average price in the rest of the country was actually lower in 2024 than in 2014, after adjusting for inflation. Meanwhile, median weekly earnings of workers were rising faster than inflation.

So, if real electricity prices were so stable, why did this narrative get so much traction? One answer may be that electricity prices were reflecting general inflation. People were angry about inflation and utility bills are a particularly salient manifestation, even if their wages were keeping up. And, of course, with growing wealth and income inequality, for millions of people wage increases were below median so they were struggling to pay their bills.

Still, as with groceries and other necessities, the point might be as much about consumers’ fears about affordability as the reality. The inflation rates we saw in much of the Biden administration triggered those fears.

(Source)

Fast-forward to 2026

Now we are a year into the second Trump administration and there’s no sign of a 50% drop in electricity prices. If you think there will be, please allow me to serve as your personal Polymarket on that bet.

Nationally, electricity prices are doing the opposite of what President Trump promised. In the year ending October 2025 (the most recent data available from EIA, which are more comprehensive and accurate, given the complexity of electricity pricing, than the BLS data often quoted), residential rates have climbed 5.2%. That’s nearly twice as fast as the rate of inflation (2.7%) over the same period. From 2024Q3 to 2025Q3, median weekly earnings rose 4.2%.

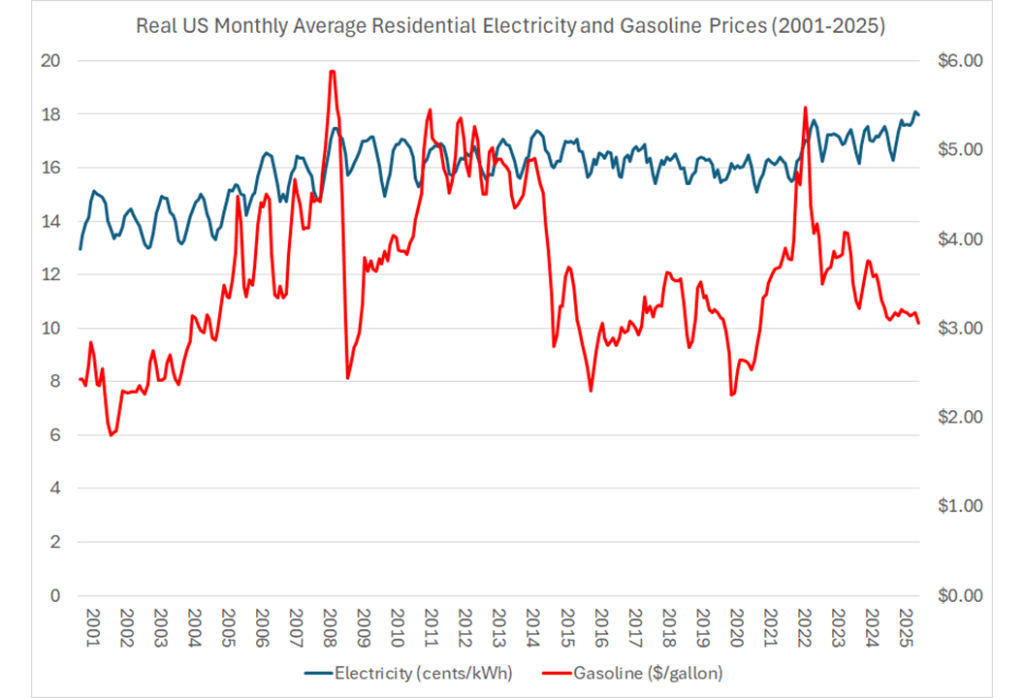

Still, even as electricity rates have accelerated in the last year, the national averages don’t suggest the sort of drastic change that would get labeled a crisis. Gasoline prices fluctuate far more in nearly every year than the electricity prices have recently, and gasoline comprises a larger share of the household budget.

State-level views

A closer look, however, suggests why some parts of the country are so focused on electricity rates: over the last decade, the geographic variation in prices has increased dramatically. Some states have seen fairly drastic rate increases, while others have seen substantial decreases after adjusting for inflation. Back in 2014, the 90th percentile state average electricity price was about 60% higher than the 10th percentile. In the last year, it was about 100% higher. (Looking at the 25th/75th percentile difference or the coefficient of variation yields the same conclusion.)

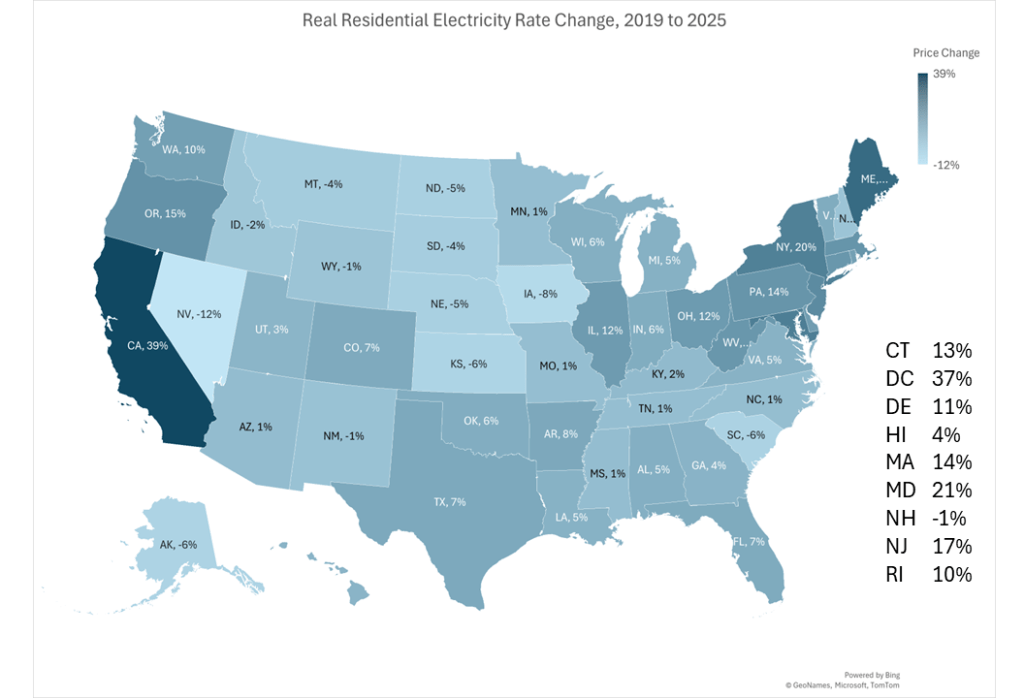

In other words, national average rates have become a much worse indicator of the electricity price that most households face. In parts of the country, rates have ratcheted up significantly even after adjusting for inflation, for instance, Washington, DC (28%), Maine (37%) and especially California (46%). And in other states, electricity rates have fallen in inflation-adjusted terms: Idaho (-8%), South Carolina (-9%), and especially Nevada (-22%).

In all, 21 states have seen inflation-adjusted rates decline since 2014 and 29 (plus DC) have experienced inflation-adjusted increases. In no state have electricity rates risen faster since 2014 than the national median weekly earnings.

These calculations made me wonder if the concern is more about recent increases than over the last decade. If instead we compare to 2019 – the last year before the pandemic – the figures are not as balanced. Since 2019, 13 states have seen inflation-adjusted rates decline, while 37 (plus DC) have seen increases. And 16 states have seen increases of more than 10% above inflation. Still, only in California and DC have rates risen faster than national median weekly earnings.

The map below shows average rate increases by state since 2019. Setting aside California, most of the high-increase states are part of the Eastern and Northeast regional transmission organizations: PJM Interconnection, the New York ISO and ISO-New England. PJM has been in the energy and political news over the last year for its spiking capacity prices and their effect on retail rates. But even in these regions, the full story is more complicated, as New York and New England haven’t seen the capacity cost increases of PJM.

A single unifying explanation

There is no single unifying explanation for the electricity affordability crisis. In large parts of the country there is no electricity affordability crisis, at least beyond the everything affordability crisis due to growing income and wealth inequality.

National political campaigns and messaging work best when they boil things down to simple stories. But good public policy generally doesn’t work that way. Rate increases in Maine and New York have different drivers than in Pennsylvania or New Jersey. And California’s nation-leading increases reflect a whole different set of problems. A one-size-fits-all solution is almost certain to be a one-size-fits-all failure.

I am now posting suggested energy readings (and some political views) most weekdays on Bluesky @severinborenstein.bsky.social

Follow the Energy Institute on Bluesky, LinkedIn, and our new Instagram. Also subscribe to our email listto keep up with future content and announcements.

Suggested citation:Borenstein, Severin. “Locating the U.S. Electricity Affordability Crisis” Energy Institute Blog, January 26, 2026, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2026/01/26/locating-the-electricity-affordability-crisis/