Using a quantum simulator cooled to near absolute zero, researchers revealed that magnetic order persists even in conditions previously believed to be disordered. Their results offer a striking insight into how quantum materials behave as they approach the superconducting state.

The finding centers around the pseudogap, a mysterious phase in the electronic structure of materials like cuprates. Rather than entering superconductivity directly from a standard metallic phase, many of these materials pass through this intermediary state. It’s a phase where electrons behave in unusual ways and where understanding the rules could unlock new advances in energy transmission and quantum technology.

According to the Simons Foundation, the team (led by experimentalists from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics and theorists at the Flatiron Institute in New York) used ultracold lithium atoms to recreate a model system. By simulating the Fermi-Hubbard model inside a precisely tuned optical lattice, they observed how spin and charge correlations behave in response to doping and temperature.

Universal Magnetic Pattern Revealed at the Edge of Chaos

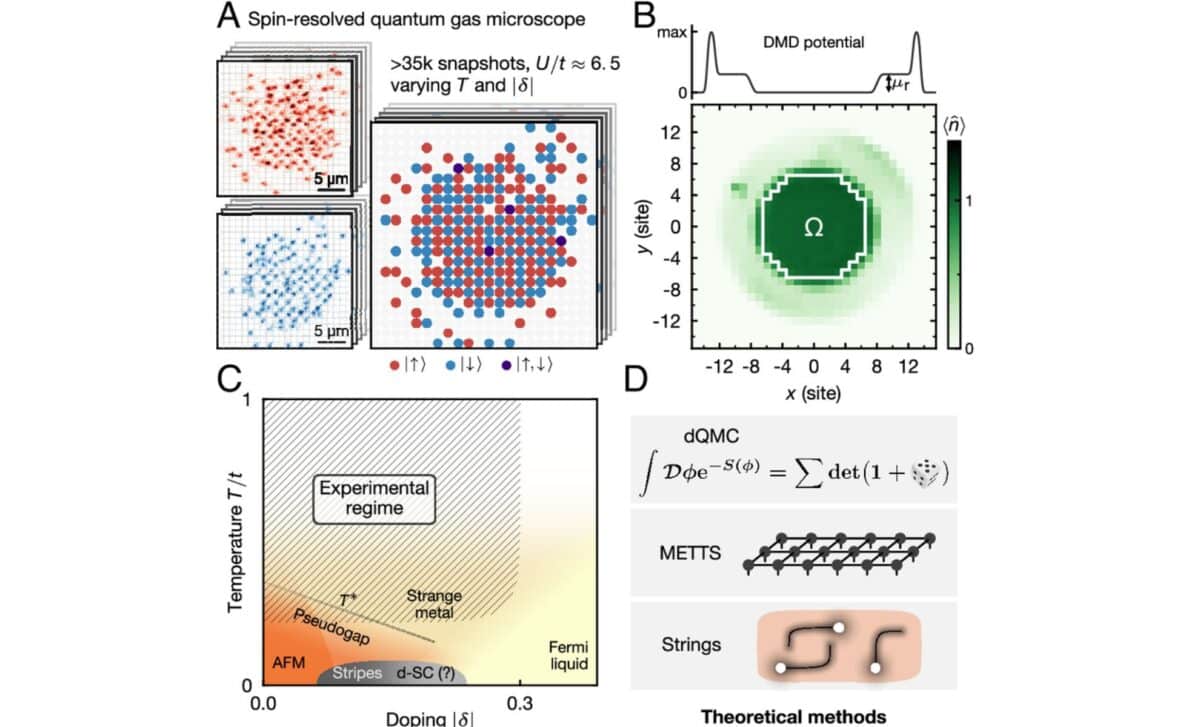

The researchers collected over 35,000 quantum gas microscope snapshots, each offering detailed views of atomic positions and spin orientations across a range of conditions. As reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, they found that magnetic correlations followed a “single universal pattern” when plotted against a specific temperature scale.

(A) Snapshots from a quantum gas microscope showing spin and charge. (B) Atomic density in the central region used for analysis. (C) Phase diagram highlighting the explored pseudogap regime. (D) Theoretical tools: dQMC, METTS, and geometric string models. ©PNAS

(A) Snapshots from a quantum gas microscope showing spin and charge. (B) Atomic density in the central region used for analysis. (C) Phase diagram highlighting the explored pseudogap regime. (D) Theoretical tools: dQMC, METTS, and geometric string models. ©PNAS

Thomas Chalopin, lead author and physicist at the Max Planck Institute, noted: “Magnetic correlations follow a single universal pattern when plotted against a specific temperature scale. And this scale is comparable to the pseudogap temperature, the point at which the pseudogap emerges.” His team’s work demonstrates that the magnetic structure is not erased by doping, as previously believed, but instead reorganizes into a more complex form beneath the surface.

This pattern persisted across a wide range of doping levels and matched up with simulations from Determinant Quantum Monte Carlo and Minimally Entangled Typical Thermal States (METTS), confirming its significance. According to the authors, the persistence of such scaling behavior points to a deep connection between hidden magnetic correlations and the onset of the pseudogap itself.

Magnetic Polarons Extend Their Reach in the Pseudogap

Another major result of the study was the detection of extended magnetic polarons, disturbances in the magnetic background caused by single dopants. These structures had been theorized, but observing their range and shape with such precision marks a new milestone.

At low doping and temperature, a single dopant was shown to affect magnetic order across more than 50 lattice sites. This means that even sparse doping has widespread consequences. The team evaluated third-order dopant–spin–spin correlations and observed that these polarons grow in extent near the pseudogap transition temperature, then shrink as temperature rises.

As stated in the PNAS article, the researchers introduced a new metric, the “polaron strength,” to quantify this behavior. The polaron strength rose sharply in the temperature regime corresponding to the pseudogap, providing another measure of the strongly correlated nature of this quantum phase. Simulations using dQMC, METTS, and geometric string theory confirmed the presence of long-range correlations but showed discrepancies at higher doping, where the experimental data diverged from predictions.

High-Order Correlations Expose Unseen Quantum Structures

Going further, the team measured connected spin correlations up to fifth order, revealing that the pseudogap regime is dominated not just by electron pairs, but by larger multi-particle structures. These complex quantum correlations lie beyond what typical Gaussian models can describe.

In one test, four-spin square and diamond configurations were evaluated. The square setup, which places spins at nearest-neighbor distances, showed strong connected correlations at low temperatures. Fifth-order spin–charge measurements showed that in the presence of a central dopant, higher-order correlations became significant, with measurable nonzero values observed around 15% doping.

These results were also confirmed by METTS simulations, which aligned well with experimental data in certain regimes. According to PNAS, “our results suggest that these string-like correlations in the vicinity of dopants persist up to about 20% doping,” a finding that was not reproduced by the geometric string model beyond 10%.

The appearance of nonzero connected correlations at high order is a rare and robust indicator of strongly correlated quantum states. This suggests that the pseudogap phase is not just a precursor to superconductivity, but a rich regime where new types of quantum order emerge, orders that are only visible when you look deep enough.