Scientists at Los Alamos National Laboratory say neutrinos could be used as a diagnostic tool to better understand what happens inside a nuclear weapon during a detonation.

The idea relies on detecting elusive subatomic particles released in large numbers during fission events, offering a new way to study nuclear performance without explosive testing.

The research explores whether an inverse beta decay, or IBD, neutrino detector could capture usable data from a nuclear detonation or a pulsed fission reactor.

Nuclear weapons produce a single, intense burst of fission that is difficult to replicate in controlled settings. Since the United States ended nuclear testing in 1992, researchers have relied heavily on simulations and indirect measurements.

Neutrinos, however, pass through matter almost unhindered. That makes them difficult to detect, but also valuable.

During a fission event, vast numbers of antineutrinos are released, carrying information about the reaction itself. Advances in detector technology are now making it realistic to capture those signals.

“With the great improvements in neutrino detection technology, the idea of using neutrinos as a diagnostic has come full circle,” said Richard Van de Water, lead researcher on the study.

“Because they’re produced so prolifically in a test event and in a pulsed fission reactor, neutrinos could offer a novel and complementary diagnostic tool for national security science.”

The team modeled a hypothetical nuclear yield and calculated the resulting antineutrino spectrum.

By combining those results with known interaction probabilities, they estimated how often antineutrinos would trigger inverse beta decay inside a detector positioned several kilometers away.

Proving detection feasibility

Their calculations show that an IBD detector could register enough interactions to provide meaningful diagnostic data from a fission event, even at a safe standoff distance.

The analysis supports the idea that neutrino-based diagnostics could complement existing tools used to evaluate nuclear weapons performance.

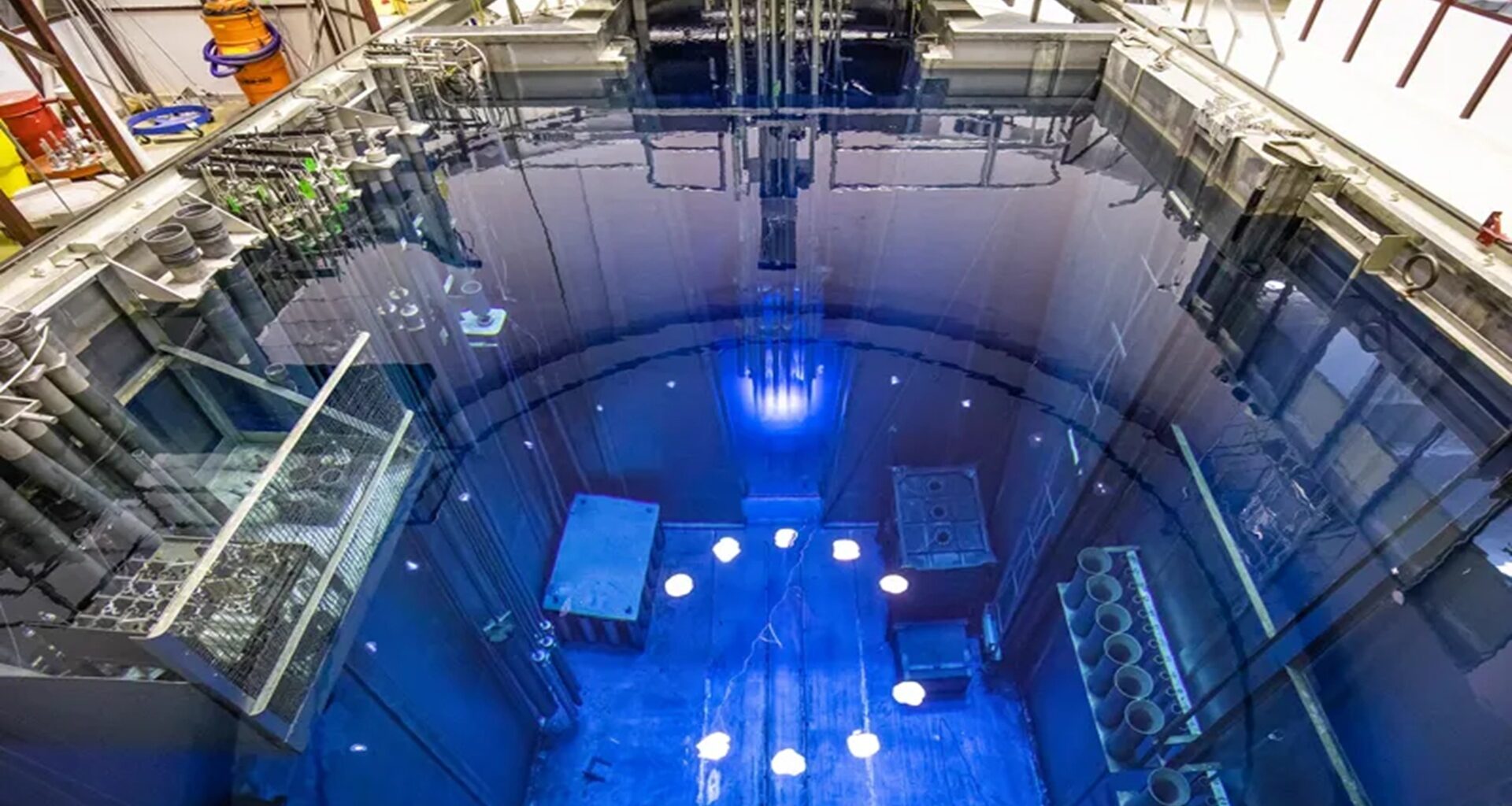

To test the concept without a weapons test, the researchers propose deploying a detector near a pulsed fission reactor. Pulsed reactors generate short, repeatable bursts of fission energy that mimic some characteristics of a nuclear detonation.

One candidate site is the TRIGA reactor at Texas A&M University. Data from such a setup could be used to refine simulations, reduce uncertainties in fission yield databases, and test assumptions used in weapons physics models.

The idea has deep historical roots at Los Alamos. Physicists Clyde Cowan and Frederick Reines first proposed detecting neutrinos using a nuclear weapons test in the 1950s.

Practical constraints pushed them to use a nuclear reactor instead, leading to the first confirmed detection of neutrinos in 1956.

Beyond weapons science

The proposed detector, called νFLASH, would be based on the Coherent CAPTAIN-Mills experiment at the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center.

Initial simulations using this design suggest the detector could capture antineutrino signals from pulsed fission bursts.

Such measurements have never been made before. Beyond weapons diagnostics, the setup could enable studies of sterile neutrinos, axions, or unexplained anomalies seen in reactor antineutrino spectra.

The short pulse structure and energy range may offer advantages not available in steady-state reactor experiments.

The researchers argue that pulsed-reactor measurements could provide data comparable to that from an actual weapons detonation, advancing both national security science and fundamental physics.

The study was published in Review of Scientific Instruments.