A man taking part in the first UK trial of Elon Musk’s Neuralink brain implant says the device has transformed his outlook on life. The experimental technology, designed to allow people with severe paralysis to control computers using only their thoughts, is now being tested at a major London hospital, raising fresh questions about the future of neurological care.

Living With Sudden Paralysis And The Promise Of Technology

For people who experience catastrophic spinal injuries, daily life can change in an instant. “It is a massive change in your life where you can suddenly no longer move any of your limbs,” said Sebastian Gomez-Pena, a volunteer in the first UK trial of the device developed by Mr Musk’s company Neuralink. His injury left him dependent on others for almost every task, a reality shared by thousands living with severe neurological conditions. The loss of autonomy often brings not only physical limits but also psychological strain, as modern life is built around constant interaction with digital tools. Regaining even partial control over technology can reshape how patients communicate, work, and maintain social ties. For Gomez-Pena, the implant represents more than an experiment; it marks a shift in how he imagines his future. “This kind of technology kind of gives you a new piece of hope,” he explained, pointing to the emotional weight carried by early successes in the trial.

Sebastian Gomez-Pena and his family. Credit: Sebastian Gomez-Pena

Sebastian Gomez-Pena and his family. Credit: Sebastian Gomez-Pena

Inside The UK Trial At A Leading London Hospital

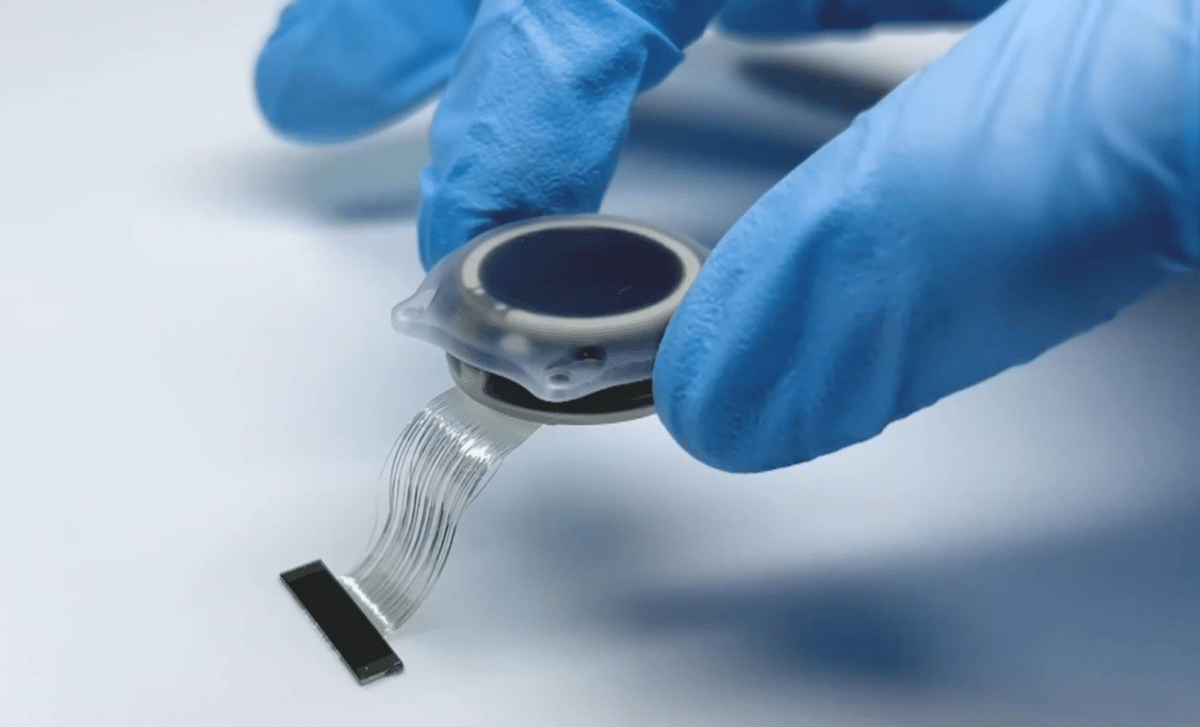

The trial is being conducted at University College London Hospitals (UCLH), placing the UK among a small group of countries testing Neuralink’s brain-computer interface in humans. The system involves implanting ultra-thin electrodes into the brain, which then interpret neural signals and translate them into digital commands. Doctors involved in the study stress that the procedure is highly complex and carefully monitored. Early sessions focus on basic interactions such as moving a cursor or selecting letters on a screen. Over time, researchers aim to expand the range and accuracy of these commands. Observing the patient’s progress has been striking for the medical team.

“It’s mindblowing – you can see the level of control that he has,” said Harith Akram, a neurosurgeon at UCLH and lead investigator of the UK trial.

His assessment reflects cautious optimism grounded in clinical observation rather than speculation.

What Doctors Say About Early Results

According to Mr Akram, the initial outcomes suggest real potential for people with profound disabilities. In his view, the early data justify further trials and broader research. Mr Akram’s opinion, the early results are promising. He believes the technology addresses a long-standing gap in care for patients with limited treatment options. “This technology is going to be a game-changer for patients with severe neurological disability,” he said. He also underlined how modern dependence on digital systems makes such tools even more relevant. “Those patients have very little really to improve their independence. Especially now that we live in a world where we are so dependent on technology.” Recent coverage by Sky News highlights how clinicians see the implant not as a cure, but as a bridge that reconnects patients with everyday digital life, from messaging to controlling smart devices.

Neuralink’s Vision And The Broader Debate

Founded by Elon Musk, Neuralink positions its work at the intersection of medicine and advanced engineering. The company states that its mission is to “restore autonomy to those with unmet medical needs and unlock new dimensions of human potential”. That ambition places the firm at the center of ethical, medical, and social debates. Supporters point to the possibility of improved quality of life for people with paralysis or neurodegenerative disease. Critics urge restraint, calling for transparency and long-term safety data before wider adoption. The UK trial adds a new layer to this discussion, offering independently monitored results outside the United States. As more data emerges, regulators and health systems will face decisions about how such technology fits into public healthcare models.