This slim volume is one of those modest but important bricks that enriches a community’s sense of itself.

These publications, often labours of love rather than professional histories, ensure that the fullest possible story of a place is kept alive.

The Great Liberties Whiskey Fire recalls an episode that may have slipped from living memory — after all it occurred 150 years ago, on June 18, 1875.

Fallon may have rescued it from the oblivion conferred by the passage of time — and deservedly so. It is a nugget in the long, long and fascinating story of our capital.

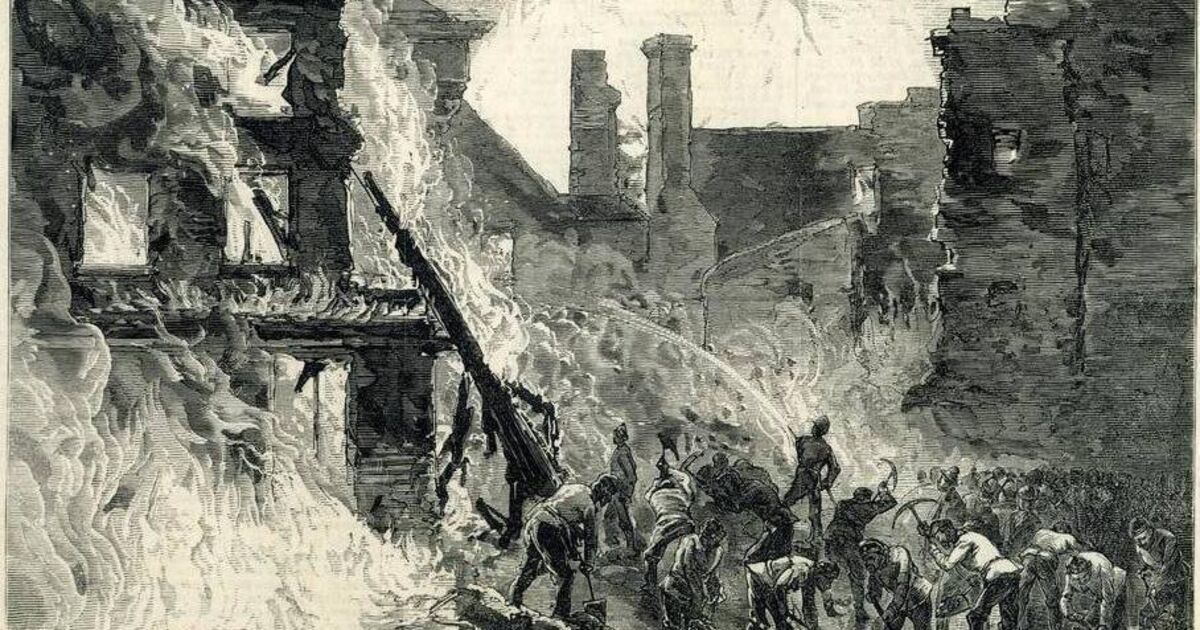

The fire started in Laurence Malone’s bonded storehouse on the Liberties Ardee St at 8.30pm in the evening where 5,000 hogsheads — 1,193,000 litres in today’s money — were stored.

It lasted just one night and caused many of these casks to explode.

A river of whiskey — some of it far stronger that usually consumed — flowed from the building, some of it alight, some of it not, and easily gathered by enthusiastic Dubliners.

The stream was said to be 15cm deep and flowed towards the Coombe.

This catastrophe was at the root of the 13 deaths attributed to the fire though none of the victims were injured by the inferno — they died from alcohol poisoning.

This gave those happy to condemn the Irish another opportunity to sneer.

An Illinois paper, The Daily Leader, thundered: “The extent to which men may become imbruted through the use of intoxicating liquers, is fully illustrated by the scenes that transpired during the great fire in Dublin last week … So hoggish did they become that several absolutely drank themselves to death while others wandered about like crazy or mad men among the blazing buildings.”

The Cork Examiner, this newspaper’s foundation stone, was less hectoring, suggesting that but for the help offered to over-stretched fire fighters by sober spectators the challenge could have become a calamity.

The extent of the tragedy in human terms is uncertain. Traditionally, 13 deaths from alcohol poisoning are attributed to the evening but Fallon is uncertain as he could not confirm that figure.

The sub-plots in these focused histories can often tell a powerful story too and this is no exception.

Fallon pays particular attention to James Robert Ingram, the man tasked with establishing Dublin’s modern fire service.

His story resonates 150 years later. He died, aged 53 in 1882, a victim of tuberculosis like so many.

He was predeceased by a three-month old daughter Norah who died just months after the fire.

After his death, his widow Emma — who inherited his estate of £348 — had to endure the death of another daughter Theresa, leaving her with just one child.

It is probable modern medicine might have prevented those deaths and preserved that family.

The Great Liberties Whiskey Fire is a short but interesting read and must encourage others with a particular interest in an almost forgotten event to put pen to paper.