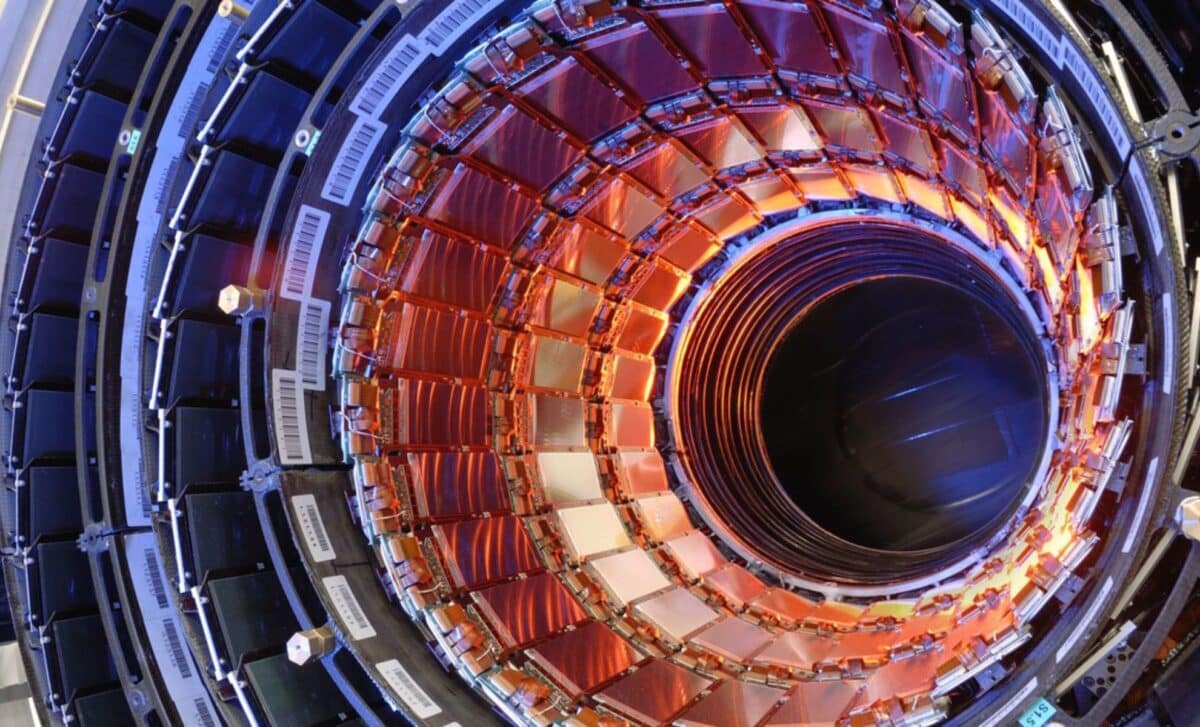

In February 2023, a neutrino with an energy 100,000 times greater than anything the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) could produce crashed into Earth, sending shockwaves through the physics community. The discovery was so unexpected that it has left scientists rethinking astrophysical models. A team from the University of Massachusetts Amherst now suggests that this strange, high-energy particle could have come from an ancient black hole, one that might even help solve the mystery of dark matter.

Normally, they come from the Sun or cosmic events like exploding stars, but this particular neutrino was different. It carried a mind-boggling energy of 220 PeV (peta-electronvolts), a level no known source can account for. According to physicists, the energy was so extreme that it didn’t fit with anything we thought we knew about space. What made it even stranger was the fact that the IceCube detector in Antarctica, which has been watching for such events for over a decade, had seen nothing remotely similar.

A Neutrino with Immense Power

On February 13, 2023, the ARCA detector, part of the KM3NeT telescope in the Mediterranean Sea, picked up a neutrino unlike any seen before. With an energy of 220 PeV, this particle was far more energetic than anything produced by the Large Hadron Collider, which is already a record-holder for particle acceleration. Neutrinos at this energy level were supposed to be theoretical, no astrophysical source was known to produce them.

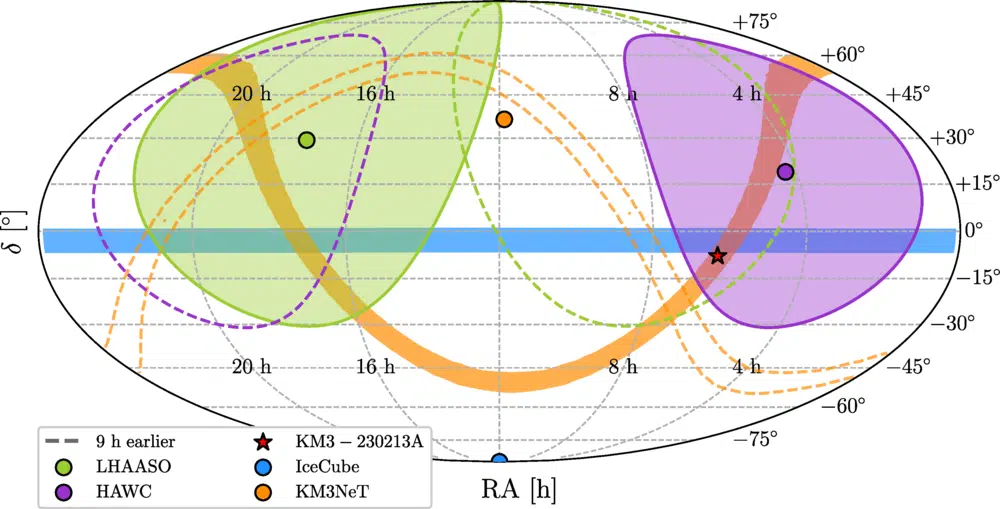

The sky map shows the regions observed by various particle detectors. Credit: Physical Review Letters

The sky map shows the regions observed by various particle detectors. Credit: Physical Review Letters

The discovery, published in Physical Review Letters, was so out of place that it triggered a lot of head-scratching in the scientific community. It didn’t fit the models we’ve built up over decades of observation. And here’s where it gets even weirder: if such high-energy neutrinos were common, then IceCube, a much larger and older detector, should have recorded a few. But IceCube had come up empty.

Could a Tiny, Ancient Black Hole Be the Answer?

Rather than attributing the neutrino to a typical cosmic event, the team at the University of Massachusetts Amherst suggested it could have come from a primordial black hole, a tiny one from the early universe. They are theoretical objects that could have formed just after the Big Bang when the universe was still a chaotic mess. These primordial black holes could be much smaller than the ones we see today, some no larger than the size of an atomic nucleus.

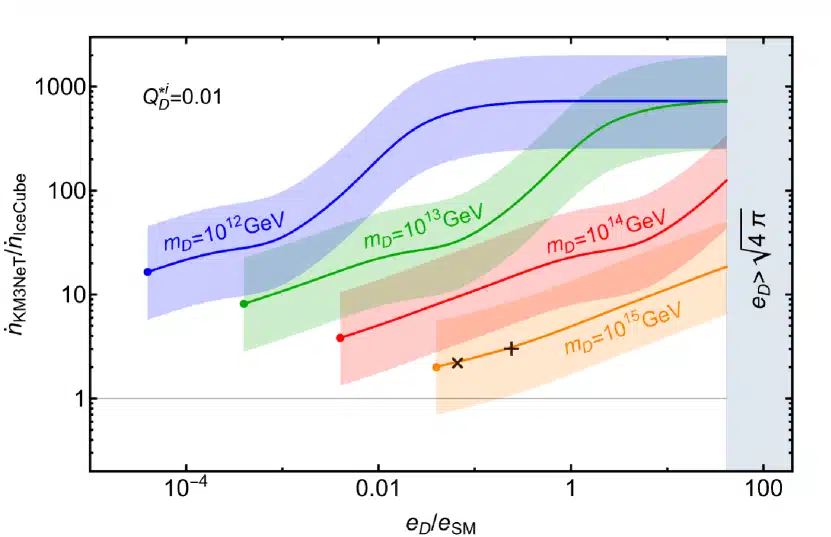

The graph shows the neutrino flux ratio (η) from KM3NeT to IceCube versus dark matter coupling (eD) for different mass scales (mD). Credit: Physical Review Letters

The graph shows the neutrino flux ratio (η) from KM3NeT to IceCube versus dark matter coupling (eD) for different mass scales (mD). Credit: Physical Review Letters

Now, this might sound a bit out there, but these primordial black holes might not be dead yet. In fact, they’re thought to evaporate over time, slowly releasing radiation in a process known as Hawking radiation.

“The lighter a black hole is, the hotter it should be and the more particles it will emit,” stated Andrea Thamm, a physicist at UMass Amherst and co-author of the new study. “As PBHs evaporate, they become ever lighter, and so hotter, emitting even more radiation in a runaway process until explosion.”

The Enigma of Dark Matter: Evidence You Can’t Ignore

So, how does this tie into dark matter? The UMass team thinks these primordial black holes could help explain dark matter, the stuff that makes up most of the universe but doesn’t interact with light. They suggest these black holes might have a “dark charge,” a force linked to dark matter, making them hard to detect.

“It gave us a new window on the Universe. But we could now be on the cusp of experimentally verifying Hawking radiation, obtaining evidence for both primordial black holes and new particles beyond the Standard Model, and explaining the mystery of dark matter,” Dr. Michael Baker, also a member of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, stated.

Usually, black holes emit gamma radiation when they evaporate, but these ones stay hidden in a “quasi-extremal” state and only explode when releasing high-energy neutrinos. This fits perfectly with what KM3NeT observed, without the extra radiation that IceCube would catch.