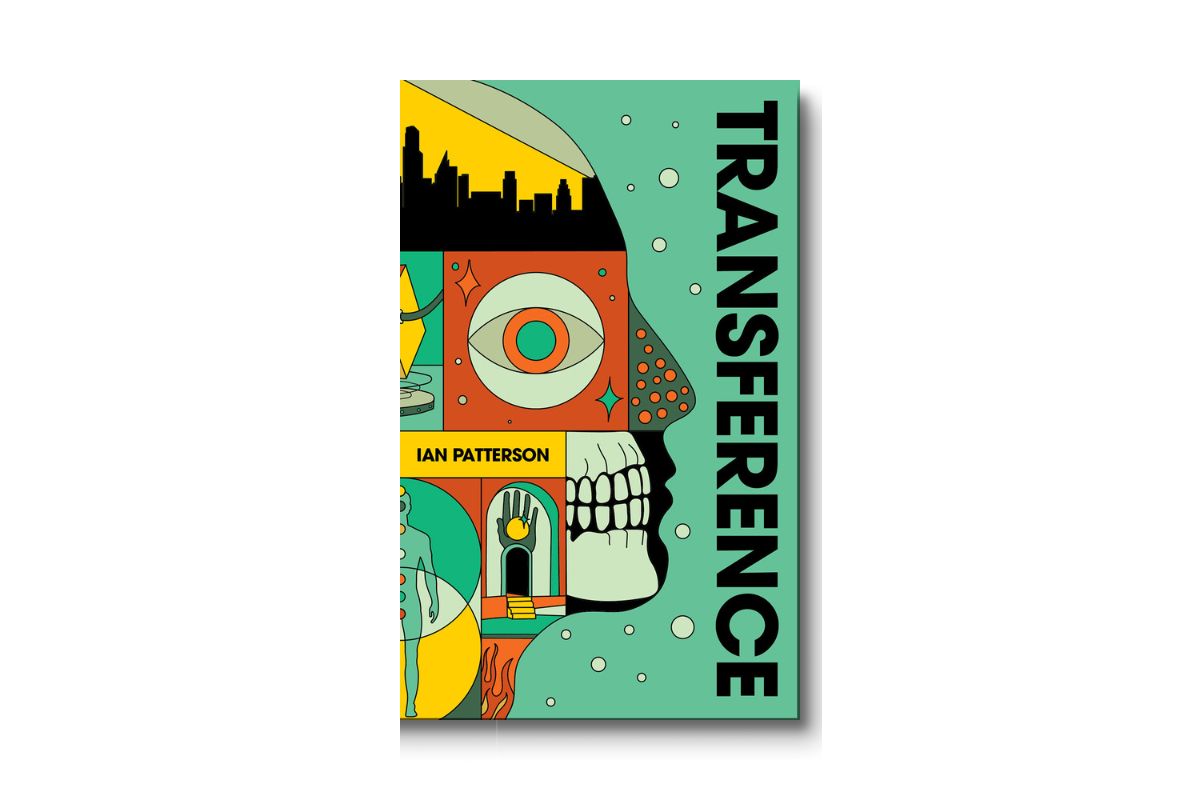

This book won the 2025 Colorado Book Award for Science Fiction/Fantasy.

From darkness, I emerge. The world is shining, impossibly bright. I clamp my eyes to shut it out. Discomfort bleeds in no matter how hard I close them. I itch and ache all over. A pile of thin blankets covers me. They’re a white so pure it hurts to look at. I have to move. I have to stand. I’ll die if I don’t.

Like a newborn again, I take my feeble first steps, testing the strength of my legs. I’ve lost coordination, certainly lost muscle. I shake my head, thick with drugs and sleep. How long have I been out? I make it to the door before some small nuisance tugs at my arm, and I tug back. Thin wires fall out of a machine on the far side of the room, and a mild beeping fills my head. Is that just in my head? I look around the room, bracing myself on the cool metal door frame to stay upright.

UNDERWRITTEN BY

Each week, The Colorado Sun and Colorado Humanities & Center For The Book feature an excerpt from a Colorado book and an interview with the author. Explore the SunLit archives at coloradosun.com/sunlit.

Some sort of hospital. It’s cramped and smells of disinfectant. Not the nice kind either, the kind they use when they think you’re not waking up. It’s full of white and silver machines that whir and blink and spin and pulse, and they’re screaming in my skull, and it’s too much I can’t fucking take it.

I squeeze my eyes shut as nausea washes over me and threatens to take my legs. My heart thrums in my ears. I grip on to the door frame with the meager hand strength I have left. I breathe in deeply, hold it, and then exhale. Eventually, my heart rate drops back down, and the nausea settles.

Thoughts force their way into my brain like needles into a formless wad of yarn. Someone will know that I’m awake, someone will come. They’ll have information, and I’ll pay them and then leave.

At the thought of payment, I panic. If you live long enough on the edge, the terror of an unknown bill can make you spiral. Adrenaline shoots through me, bringing with it some much needed clarity, and I flip my left wrist and navigate the screen installed there until it displays my credit balance.

I can feel my eyes bulging as my legs go weak again and threaten to collapse under me. How big of a job had this been? Holy shit, how much did I gamble? It’s more money than I’ve ever seen. Breathe, just breathe.

The door to my room swings open behind me, and I lock eyes with someone who looks familiar. He’s tall, wearing a white lab coat with a short graying beard, and has a very stern look on his face. He’s handsome, in a grizzled, fatherly way. His face tugs at my memory, but nothing surfaces from those murky depths.

“Transference”

>> READ AN INTERVIEW WITH THE AUTHOR

Where to find it:

SunLit present new excerpts from some of the best Colorado authors that not only spin engaging narratives but also illuminate who we are as a community. Read more.

He breaks my gaze, and shaking his head, sighs. “Sit down before you give yourself a heart attack too, Nicholas.” He motions back to the bed. I mechanically make my way to it, and sit.

Taking a stool across from me, the man adjusts his lab coat and then continues. “Here’s the story, you took a big one, a real fucking nasty one, and I was pretty certain you weren’t coming back. Now I expect that you’ve got some short term amnesia so I’ll fill in some blanks. Stop me if it starts coming back so we can talk about more interesting things.

“Your name is Nicholas, my name is Brian. We’ve known each other for a decade, we’re friends, but some days I really wish we weren’t. You’re a Sicko.” The name stirs something in me. “That means you make a living trading money for taking on other people’s diseases. It’s a fucking stupid existence if you ask me, but you hire me to look after you and keep you alive, and I get a cut of your earnings.”

With a sudden anger, he grabs my wrist and flips it over and taps his pointer finger against my screen. “Did you see how much coin is on this thing? That’s after you paid me too, I wanted payment before the procedure because your odds were pretty bad. Now that’s enough to quit, so stop fucking doing this. I am tired of piecing you back together.” He accentuates each of these last words with a finger thump on my wrist, and after a long pause he says, “I don’t want to see you die on my gurney.” He looks away.

Scattered memories start to flood back in. A handshake in a dark room with someone smoking, sitting in a sterile room with my body plugged into a disease transfer machine, Brian yelling at junior staff and shaking some images, a machine showing erratic vitals, and then absolute darkness.

“How long have I been out?” I ask, slowly. Talking is difficult. My tongue feels alien, too thick, too rigid. I have to concentrate on each word. They come out heavy and wrong, like my mouth is full of cotton.

“Three months in a medically induced coma, one month of treatment before that. At first, you were heavily drugged to keep the pain levels low. And when—” He makes a small choking noise, and then continues after a pause. “And when we knew you probably wouldn’t make it we had to put you under so your body could focus on healing.”

I’m stunned. My eyes find the mirror behind Brian and it’s painfully clear what the time has taken from me. There are bones visible through my hollow, pale skin. My already angular face is sunken now, outlining my high cheekbones, sharp nose, and narrowed green eyes. My head is bald except for a few long straggles of black hair. I don’t remember being an attractive person. Now I’m terrifying. Shaking, I ask in a small voice, “What the hell did I take on?”

🎧 Listen here!

Go deeper into this story in this episode of The Daily Sun-Up podcast.

Subscribe: Apple | Spotify | RSS

“Cancer, a particularly nasty lung cancer. The bastard you traded with lied. I fucking told you he would, but you saw the money and went for it anyways. Stage one he said. Hah! No, it was fully metastasized. He showed you old scans, hired fake doctors to convince you. He probably figured you’d die, because that’s what Sickos do. You bite off something too big and it takes you out, and those rich, smug fucks get to keep on living lavishly.”

“Can I report him to anyone? That kind of shit’s got to be illegal–”

Brian interrupts me. “What, did you lose your brain while you were under? Illegal?! No one gives a shit what those cats do. You report him and the best you could hope is that the Inquisitors ignore you, otherwise you might wind up in a gutter at the bottom of the Boroughs. Just be happy you woke up from this one, that’s the only thing you’re going to win today.”

Brian stands up and walks towards the door, but something gnaws at him. He pauses and turns back. “Look, kid, you’re going to be fine. Your cancer markers are back to baseline, and somehow you even woke up from your coma. I’d say it was a miracle if I believed in anything like that. Now, you’re going to rest in this bed, I’m going to send down some really shitty hospital food, and you’re going to eat it all and think about what you’re going to do with your time now that money’s not tight. And you better not tell me you’re going to take on another job, or I’ll kick your skinny ass.”

“Do you mind bringing the food back yourself? I might have some more questions by then.” Memories have started to come back, images through a haze of smoke, and I know a lot rides on what moves I make next.

Brian rolls his eyes, turns, and shuts the door behind him without responding. Smiling, I lay back down and close my eyes. I like Brian, he’s a good sort.

The Disease Transfer Machine, or the Box as we call it down here, was invented some time before the city. It’s always existed here, the primary thing shaping our lives. It sounds noble at first, the elimination of disease, until you realize it only works that way if you can afford it. For those of us in the lower levels, it’s the thing killing us. It’s the only job we can find. It’s the poison that we can’t stop eating.

Do I know how it works? Not a fucking clue. One person sits on each side of the giant metal box, various tubes extend from it and connect to each of them. There’s a giver’s seat and a receiver’s seat, and no one else in the room when they turn the thing on. It’s a strangely intimate thing, sitting across the room from your destroyer. There’s a feeling of great suction all over your body, and then the misery sets in. The symptoms start like a bucket of ice water dumped on your shoulders. I’ve always wondered what a great relief it must feel like on the other side.

The backbone of our economy is built on it. The very rich trade their diseases to the very poor for appropriate compensation agreed on by both parties. But realistically, when you’re poor enough you’re too constrained to know what appropriate compensation is. Some people have tried to create laws around it, establishing contractual requirements and base pay for different diseases. They don’t mean much though, there was always someone willing to go under the base pay, there was always someone that needed the money badly enough to take the risk. Laws just give the illusion that what’s happening is fair. Of course, it’s not.

This new caste of people, the perpetually ill, were lovingly nicknamed Sickos. The working poor hated them for the ease they got their money, the middle class decried the horrors of rampant capitalism they represented, and everyone tried to buy their services when their own bill came due.

Ian Patterson has dreamed of being an author for decades, but finally began the journey with the birth of his first daughter. This is an objectively terrible time to start work that requires quiet concentration, and he knows it, but he loves the chaos nonetheless. He has lived in various places along the Colorado Front Range for the past 25 years, and currently resides in Colorado Springs with his family.

Type of Story: Review

An assessment or critique of a service, product, or creative endeavor such as art, literature or a performance.