In the December Financial Stability Report, the Bank of England signalled that it is looking again at how the UK’s bank leverage ratio is implemented—with particular focus on the calibration of leverage ratio buffers. The timing is not accidental. The same report noted that the leverage ratio is now the binding capital constraint for three of the seven major UK banks.

In plain English, these banks are no longer constrained by the risk-weighted capital rules—where required capital reflects how risky the assets are judged to be—but by a simpler “backstop” that caps how much a bank can borrow relative to its equity capital.

The FPC says it will review the leverage ratio framework “to ensure it functions as intended”. That is bureaucracy-speak for “we’re reviewing whether to relax the leverage ratio regulation”.

TL;DR: The leverage ratio is doing its job. A systemically important bank can already run with common equity leverage of around 30x. If the backstop is now binding, that is a warning that risk weights have become too flattering—particularly for banks’ exposures to the non-bank financial system. The right response is not to weaken the guardrail but to recalibrate the risk weights in the areas driving the drift.

What is the leverage ratio?

A good way to see what the leverage ratio is doing is to start with mortgage lending. Under the standard “risk-weighted” approach, large banks estimate the risk of each mortgage: how likely the borrower is to default, and how big the loss would be if they do. Regulators then translate those estimates into a capital requirement—in effect, the slice of the loan that must be funded with shareholders’ equity so that losses can be absorbed without the bank failing.

In principle, that sounds sensible. In practice, models can understate risk after long benign periods, and incentives to boost return on equity push measured risk (and hence required equity capital) down over time.

That is where the leverage ratio comes in. The leverage ratio is a blunt backstop: it requires banks to fund their overall loans and other assets (“exposures”) with at least a minimum amount of capital, irrespective of the modelled riskiness of those exposures. Put differently, it caps how much the bank can lever up its equity.

The bluntness is a feature. Consider a loan to a large company. Under risk-weighting, the bank would again model default probability and loss, with capital set accordingly. The leverage ratio, by contrast, insists that the bank must fund both the mortgage and the corporate loan with the same share of equity capital, even if the models say one is much safer than the other. The point is not to be a perfect measure of risk. It’s to ensure that if risk models are wrong—or incentives push risk weights down too far—the system still has a minimum layer of loss-absorbing capacity.

History gives plenty of reasons to want that guardrail. Before the Global Financial Crisis, flawed risk weights and the absence of a leverage ratio allowed bank leverage to reach extraordinary levels (see figure below). Today, sovereign bonds still carry zero risk weights. Empirical evidence after the 2008 crisis showed that simple leverage measures were a better predictor of bank distress than risk-based counterparts.

The leverage ratio was never intended to be the main capital constraint in normal times. It is supposed to sit behind the risk-weighted framework as a backstop—an insurance policy against model error and misplaced confidence in “low risk” exposures.

Wonk warning: the next paragraph does a bit of leverage ratio arithmetic.

Its calibration reflects that backstop idea. The FPC sets a minimum leverage ratio of 3.25% (excluding central bank reserves)—meaning roughly £1 of Tier 1 capital can support £31 of loans and other exposures (i.e., 1 / 3.25% ≈ 31 times leverage). But that understates leverage permitted on core equity because only 75% of that minimum has to be met with core equity capital. So the true core equity floor is just 0.75 × 3.25% = 2.44%. Systemically important banks face additional leverage buffers on top, which must be met with core equity capital. For Barclays, for example, those buffers add around 0.8pp, bringing the core equity requirement to about 3.2% of exposures—implying leverage of around 30x (1 / 3.2%) on common equity.

Thirty times leverage on core equity is a very large number. So it’s pretty alarming that the leverage ratio has become the binding constraint for a material share of major UK banks.

Why has it become binding?

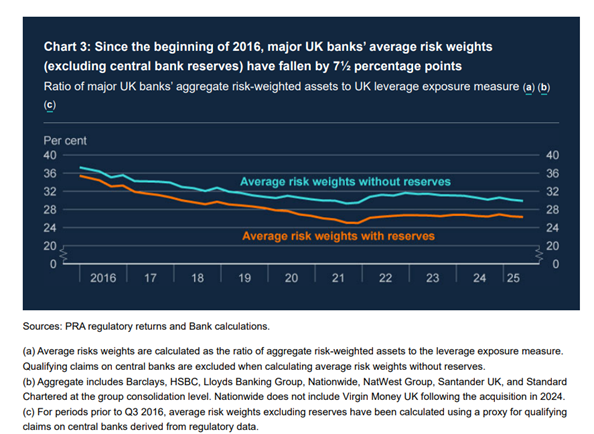

Arithmetically, the answer is simple: average risk weights have fallen over time.

The chart below, taken from the Bank of England’s report, shows that average risk weights have declined from around 37 per cent to around 30 per cent over the past decade. Bank staff estimate that this equates to a fall in required capital of around £60 billion for the major UK banks—relative to what would have been the case had risk weights not declined.

Why have risk weights fallen in this way? Part of the story is a shift in what banks do. Banks have increased their exposures to activities that attract low risk weights—most obviously sovereign holdings, but also large volumes of secured financing and intermediation activity. Another part of the story is “within-class” changes: even holding the mix of activities constant, measured risk on some exposures has drifted down, reflecting model recalibrations, supervisory judgements, and changes in how exposures are structured and reported.

The most important channel is the one that sits at the boundary between banks and non-banks. A growing share of credit intermediation now happens outside the regulated banking system—in investment funds, private credit vehicles, broker-dealers and other “intermediate other financial corporations” (OFCs). Banks are not absent from this world. They increasingly provide it with funding and liquidity: collateralised lending, margin finance and repo-style intermediation, as well as credit lines that can be drawn in stress. (See the House of Lords Financial Services Regulation Committee’s recent report on private markets and private credit.)

You can see this in the Bank of England’s own Bankstats data. Bank lending to non-banks involved in financial intermediation (excluding insurers and pension funds) has accelerated sharply over the past year, with the 3-month annualised growth rate reaching nearly 30 per cent (see chart).

This matters for the leverage ratio debate because much of this activity can look “low risk” in a risk-weighted framework—it is secured, often short-dated, and structured in ways that minimise measured credit risk. It expands banks’ total exposures (and therefore the leverage denominator), even if it doesn’t increase RWAs by very much.

A further reinforcing dynamic is significant risk transfer (SRT), where a bank buys protection on a slice of losses on a loan portfolio—say, from a private credit fund—allowing it to reduce the RWAs on those loans. But the exposures remain on balance sheet, so the leverage ratio is unaffected.

One final point on housing. Mortgages are not the main driver of falling average risk weights, but they remain the single biggest pool of low-risk-weight exposures on UK bank balance sheets. In a system with a very large stock of low-risk-weight mortgages, it doesn’t take much additional balance-sheet growth elsewhere for the leverage backstop to bind.

What should the FPC do?

The UK put the leverage ratio in place as a backstop against model risk and the tendency for risk weights to drift down. That drift has been material, and the leverage ratio is now the guardrail preventing that process from continuing further.

So what should the FPC do? There are three broad options.

Option A: Weaken the guardrail

The argument for easing is straightforward. The UK’s leverage ratio framework includes buffers that go beyond the Basel minimum. If the leverage ratio is now binding, it is tempting to conclude that the fix is simply to pare those buffers back.

I think that would be the wrong call.

The UK is a large international financial centre, with a banking system that is large relative to GDP and tightly intertwined with global markets.

The UK also has limited fiscal space to absorb the consequences of a systemic banking shock. It has been argued that credible resolution regimes have removed the need for fiscal bailouts. Resolution has worked for small banks such as SVB UK, but has never been tested on a large, systemically important bank operating across multiple jurisdictions. And even if resolution does prevent direct recapitalisation costs, it does not prevent the macro-fiscal fallout—recessions, lost revenue, fiscal stimulus—that typically does the real damage. A well-known study reports that the median rise in public debt after a banking crisis in advanced economies is around 21 per cent of GDP.

Moreover, on the FPC’s own analysis, risks have increased.

Weakening a backstop that already permits 30x leverage on core equity is the wrong direction of travel.

Option B: Do nothing – let the leverage ratio bind.

A second option is to leave the regime unchanged and simply accept that the leverage ratio will bind for some major banks for a period of time.

The problem is that a binding leverage ratio can distort incentives at the margin. Once the leverage ratio is the binding constraint, the capital cost to the banks of expanding the balance sheet becomes insensitive to measured risk. A bank faces the same capital requirement on all new lending. As a result, we could see banks discouraged from mortgage lending in favour of higher-yielding (riskier) exposures. At a minimum, there would be a need to understand the mix of activities the regime encourages when the backstop is binding.

Option C: Fix the risk-weighted regime

The third option is the one the facts point toward: treat a binding leverage ratio as a warning light that something has gone wrong on the risk-weighted side. The right response is not to weaken the backstop but to ask whether risk weights have become too flattering in key areas—and to recalibrate them if so.

That is not necessarily easy. It may require changes to models or floors; it may require revisiting the treatment of certain secured exposures and facilities; and, in some areas, it may require the UK to make the case internationally. But it is the right solution: keep the guardrail, and fix the thing that is pushing banks into it.

A binding leverage ratio should be treated like a fire alarm: the prudent response to hearing one is to investigate the source of the smoke, not remove the batteries.

Some questions any review of the leverage ratio should answerWhat tail scenario would generate losses on exposures that look “low risk”?What does the reverse stress test look like for mortgages, sovereign bonds, and bank-NBFI intermediation? In particular, how confident are we in stress test results for a sustained house price fall combined with higher interest rates and rising unemployment—a scenario for which models have limited historical experience?Why have RWAs fallen – and how much of that is supervisory/model-driven?What changes in models, calibrations, SRT recognition, and supervisory judgements have contributed to the compression in RWAs?Would easing leverage deepen bank-NBFI linkages and raise systemic risk?Would it accelerate secured financing and credit lines to NBFIs, tightening feedback loops in stress? (In a recent paper with colleagues at KCL, we model bank-NBFI linkages in the SRT market and find a U-shaped relationship between credit-line intensity and systemic risk)If we relax it when it binds, is it still a backstop?How much true equity leverage are we comfortable with?If the leverage constraint on common equity for a systemically important bank can be on the order of 30x, what is the case for increasing it?